PseudoPod 959: Powers Of Darkness

Powers Of Darkness

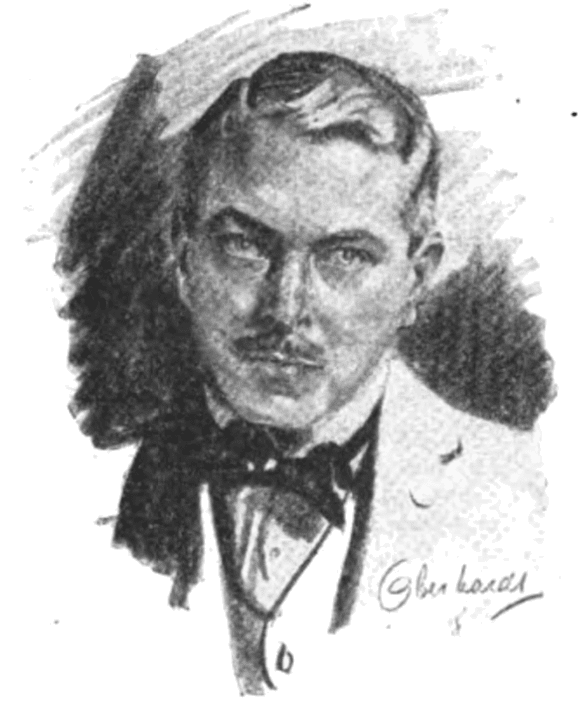

By John Russell

Nickerson, R.M., failed in judgment concerning his guest Dobel. This was the reason of his ordeal that night at Warange Station: a black night and a bitter ordeal. If Dobel had been a cannibal or a headhunter—wandering thief or fugitive murderer—Nickerson would have made no mistake. But himself he was a gentle soul, trained merely in all forms of conceivable wickedness, and although he disliked the gross stranger with the sly and slitted red eyes he had no intimation of the fellow’s real nature. Not until Dobel showed such an utterly brutal manner of disbelief.

At the very first demonstration of the native Sorcerer—at the very first piece of native magic which Nickerson had been at diplomatic pains to stage and arrange for him—Dobel grabbed an empty beer bottle. “You black-faced swine. Dried shark liver!” he rumbled. “Try and fool me with your dam’ faking tricks, will you?”

He made a motion as if to crown the Sorcerer, kneeling quietly there on the mat beside them, when Nickerson let out a cry, involuntary. “For God’s sake, stop it, Dobel. Stop it—I say, you drunken idiot. . . . The man’s my friend!”

Evidently Dobel had not really meant it just then: it was rather his line of humor, his revealing gesture. For he stopped and put down the bottle and leaned back in his chair again, with a grunt.

The two white men were sitting at dinner in Nickerson’s palisaded station at the far end of the world. By way of information, the far end of the world is Papua. This is not only geographic, it is also entirely authentic, being well known to everybody who has survived it in person. Papua remains the last mystery on this big round globe. It remains largely impenetrable and unpenetrated beyond a coastal strip and a few gold mines. It remains an active hell of heat, fever, violence and sudden death. In fact, it remains . . . Whenever a hard-working explorer casts about for some place to get lost and to write his next book, he considers Papua on the map and then goes somewhere else.

However: Nickerson was used to it. For some years he had been what is called a “Resident Magistrate” in the nominal government thereabouts. This meant that he personated the whole British Empire over a theoretical “District” of monstrous mountains and reeking jungles. It also meant that he was supposed to control various unconquered tribes of large, muscular and extremely serious-minded black gentlemen who have been cannibals and headhunters from time immemorial and who see no particular reason why they should change their habits at the behest of strange armed intruders. As if messengers from Mars should suddenly descend upon us and make us all eat grass. But Nickerson had done very well. With his handful of native police he had won his wilder charges to a moderate righteousness. He liked his work: yes, and he liked his black folk, because he respected them as lost ancestors of ours left over from the Stone Age, with many singular gifts and virtues of their own. So they in turn respected him, and even obeyed him sometimes.

Dobel…. Well, Dobel was quite a different person. Nickerson had received him as he did all dispensations, with the same kindly simplicity, and with no more than a vague suspicion that there occurs from time to time such sort of commercial adventurer for the chastening of every colonial administrator—inevitable as the worm in a walnut. Arriving from nowhere, equipped with credentials, a brazen assurance and an unholy familiarity with the waterfront dives and lingos of a dozen tropical ports, Dobel had announced himself a coffee planter proposing to develop the country. In which capacity, of course, he could claim aid, hospitality and protection at Nickerson’s station of Warange. This he managed off-hand, and meanwhile conveyed without too much subtlety an opinion of his host, his host’s ideas, methods and general worth that might have provoked the mildest man. But Nickerson—poor chap!—he was the mildest man. And thus one word leading to another, and because after all they were the only two whites (outside the Brothers at Warange Mission) in a howling wilderness together, the little R.M. had finally invited his uninvited guest to the private proof and demonstration as hereinbefore stated.

He was already sorry for it. He was due to be a great deal sorrier. . . .

“Make him do it again.”

“That’s not quite fair, is it?” protested Nickerson.

“Didn’t you say you’d show me some native stuff I couldn’t explain?”

“I did. And you couldn’t. And many others have tried—and couldn’t.”

“Well, you called him a friend,” sneered Dobel. “Is he afraid to try it over?”

All this while the Sorcerer had stayed resting on his mat beside the table. Certainly there never was a sorcerer less under implication that he should roll up his sleeves. Naked except for a bark strip about his middle, he resembled some image in polished basalt from before the days of Egypt. Anywhere else he would have been amazing: here he was magnificent, with the features of an ancient Assyrian king—the hooked nose of power and the mouth of imperious pride. He stayed motionless and inscrutable, as becomes a high chief and a master of magic in Papua, until at Nickerson’s quiet word again he proceeded to oblige.

Now, his magic was this:

Taking in his hands a few loose seeds of pandanus, with appropriate incantation he tossed them sharply into the lamplight. There they hung suspended an instant, when they took miraculous life of their own, spreading the wings of yellow and crimson moths that fluttered and circled as a brilliant flake-storm—melting away at last with the shadows.

At least, so it seemed, and the seeming was a gracious and a harmless fancy.

Perhaps such qualities were especially irritating to Dobel. Perhaps one of those synthetic insects flipped past and made him jump. Or perhaps the true animus of the man lay bedded in something deeper, of which his skepticism was merely the fat layer. At any rate, he liked it no better than the first time: once more he flushed with evil anger.

“Dam’ blasted faker! Pig-snout—” he began to growl. But once more he checked abruptly: and this time for a very special reason.

A new and surprising figure had just glided in between the bead curtains of the inner verandah, carrying a tray with their next relay of drink.

Through their meal together the two white men had been waited upon by Nickerson’s houseboys: rough-handed and half-tamed products of the cannibal frontier. But this was a girl! A girl, and the like of a girl to draw the bloodshot gaze of any Dobel, East or West. “What—ho!” he gurgled.

A native girl in a white man’s house?

What made it better (or worse), she was attractive by any standard: slim and lithe. She wore a single white garment of the sort supplied by missionary enterprise for the suppression, one supposes, of the female form divine. But this garment had been often laundered, and if its effect was not displeasing the young lady herself seemed not unaware. No. If old Mother Hubbard had garbed her, old Mother Eve had endowed this copper-bronze child of hers with something much more elemental. It showed in the provocative face with sweeping lashes. It showed in the willing grace with which she leaned over to pour Dobel’s glass. Timidly. Yet not too timidly, either. . . .

Well, of course there are things that merely happen, and there are other things that merely are not done. All depends upon how you look at them and how much you know. And who should know better than Dobel, who seemed to know everything?

“Well, well—!” he murmured, very softly, for him. He looked with great favor. He looked with very particular favor. Nickerson was paying the girl no attention whatsoever. Neither was the Sorcerer. Which left Dobel her sole appreciator.

He was highly appreciative. He watched while she filled the drinks. He watched and let his slow gaze run along the smoothly perfect contour of cheek and arm. He continued to watch when she moved noiselessly away to the bead curtains, and there paused to flash back a look at the gross white man that made him wet his thick lips and chuckle in his thick throat. . . . Nevertheless it was his further humor to say nothing about her—to make no comment. Not yet. When he did speak, he was grinning.

“Ah. Very pretty. But it’s only tricks.”

“You saw what he did?”

“I saw something. But I hate to be fooled by a nigger. No— nor anybody else!” added Dobel, with a red glint. “Nobody fools me much!”

“Dobel—” Nickerson was almost pathetic. “It’s my job to steer you through and make you successful, and all that. But if you’re going to stay in this country you’ll have to change your way with these people. One thing: you must never use that word. They’re not—what you said. They’re not a subject race at all. And we hold them none too safe, if you know what that means. . . . Heavens, man—you can’t hit a native!”

“No?” drawled the other. “You can’t hit ’em. And you can’t love ’em either, maybe?”

“That’s true.”

“I’ve heard a lot of such talk…. It don’t mean a blasted thing.”

“It means we’re dealing with one of the most powerful chiefs —a gentleman in his own fashion. It means he has to be treated properly.”

Dobel gave a bark of amusement. “Listen: I’ve dealt with all shades of natives, black to pea-green—for twenty years. D’you think you can teach me anything? If you do—carry on with the show!”

Nickerson hesitated. He had lived too long in the unaccountable spaces of the earth: he had forgotten how to account for a type like Dobel. He served a friendless Service, devil-ridden by political amateurs (Papua is not a Crown Colony, worse luck!). But, poor pay and all, he needed his place for his family back home. What if this annoying, accredited guest should start up complaints at headquarters? The mere thought gave him a shiver familiar to every empire-builder. Did people really act so? As a matter of fact, he could not tell: any more than he could judge just how drunk Dobel might be: any more than he could gauge the precise peril behind those sly and slitted eyes. At the present moment the fellow seemed not too awfully drunken—he was keeping a grin quite amiable with his gaze fixed over yonder toward the curtains somewhere. . . .

All of which will indicate the perplexity of Nickerson, R.M., and the reason of his mistake, as aforesaid. For presently he consulted again with the Sorcerer. (It was curious how he gained ease and confidence with that language.)

“I’m sorry, Dobel,” he announced at last. “The old boy doesn’t much fancy you.”

“No?” ‘

“No. He says if men like you had been the only white men in Papua, he would own a lot of fine smoked heads. . . . I’m quoting his drift.”

“Yes?”

“Yes. And for that reason, as nearly as I can make out, he is willing to show you just one more thing you can’t explain.”

“Carry on,” repeated Dobel.

Now, the only visible possessions of the Sorcerer were these: on one side of him his keen little belt-axe, and on the other his grass-woven sack. The weapon he had discarded in courtesy. The sack he kept for his oddments and conjuring stuff—his bag o’ tricks, so to speak.

From out of that bag he dragged forth next an object which he threw with a limp flop on the mat before them. Not a pleasing object. It was a baby crocodile about ten inches long, and quite evidently it had passed some time ago from this crocodile vale of tears. It was already blue, the scales loosening from it. “He wants you to be sure this creature is dead,” explained Nickerson.

“Faugh! . . . Guess I know a dead croc!”

“You’re sure?”

“Of course,” growled Dobel.

“Then hold tight,” said Nickerson.

The Sorcerer exhibited a fragment of ordinary greenstone, delicately shaped, about the size of an arrowhead. Taking it between finger and thumb like a pencil, he began carefully to stroke the point. Then very gently, very slowly, he stroked the crocodile from head to tail. Some way, but in the way of an artist, he brought to that fantastic employ a silent suspense that grew and grew almost tangibly. Kneeling there in the aura of light, the big black man stroked gently—gently. And slowly—slowly, the result appeared on the dead animal. A pulsation ran through its flanks. Its scales brightened to a pallid green, firmed and quivered. All at once its sunken lids lifted on two gleaming, pin-pricked nodules. It stood propped on its four legs. And at the final touch —impossibly, unbelievably—with a flirt and a whisk it rattled over the mattings and was gone! The thump of its escape outside made an end to that manifestation—also an end to Dobel’s restraint.

He rose with a roar. He wanted no bottle this time. All he used was his fist, and a fist cruel as a knotted club, and he swung it with scientific impact squarely to the jaw.

Like a cloud across the moon, like the dark wind that slashes some sunny beach, so quickly they turned from comedy to tragedy —never far apart anywhere, it may be, but surely never as close as in this strange, deep and untamed land: tragicomedy and tragedy not very comic in Papua. . . .

“Good God!” Nickerson whispered.

As if stricken by the same foul blow he dropped on one knee by the victim who lay limp and helpless as any crocodile, an inert heap. “You beast. . . . You unspeakable beast!”

Dobel stayed straddled. “That’s a’ right. ’S only a sleep punch.”

“How—how could you!”

“Time enough, too. I told you nobody was making a fool of me.”

“Fool—? Have you any sense of what you’ve done? All his fighting men are camped outside the gates. Enough to swamp us, and the whole district! . . . Death is out there. Death!”

True, in the hush they might have been aware of Papua around them, stirring in the night. From the savage camp came the soft throb of a tom-tom, like the beating of a heart. A sigh passed in the jungle, stealthy and sinister—a hot breath that is like nothing except a tiger’s throat.

But it meant nothing to Dobel—he only stayed grinning—and the sight of his hateful, impervious sneer was more than Nickerson could stand: it drove him near to madness. “Besides—when I—when I said he was my friend!” he half-sobbed, and simply threw himself at the fellow. Another mistake and about the worst possible, of course, though doubtless the sort Dobel had been playing for. Gleefully he took the little R.M., twisted him easily as a banana stalk, slammed him against the wall.

Appalled—almost stunned—still Nickerson made the proper official effort. “That stops it, Dobel. You’re going out of here. I’ll have you deported. On the coasting-steamer tomorrow. . . . Consider yourself under arrest, sir!” With a shaking hand he felt for the police whistle on a cord about his neck.

Before he could touch it, Dobel ripped it away and bulked over him, the whole brutal assurance of the man projected like a cliff.

“Me going out? Y’ sop and weakling—why, that’s exactly what I come to do for you! . . .

“You didn’t guess it yet? Why, I knew all about you, Mister Resident Magistrate, before I ever started here. Sure. Your record at headquarters: y’r silly reports on native habits and customs and such. Ho!” He gave his bark of laughter. “ ‘Habits an’ customs.’ Soon as I saw that, I knew where I’d catch you. Says I, ‘Leave him to me. I’ll get that dam’ nigger-loving R.M. out of there!’ ”

Dazed—bewildered—still Nickerson was able to ask the proper official question.

“ ‘Order’?” echoed Dobel. “Order be blowed. No—I ain’t in your service. I represent a company that gives their orders to any service. We hold a concession for this distric’. But first we reckoned to be rid of you. And how easy you made it! What? Did you never hear of laws and regulations—Section 89—against ‘witchcraft or sorcery, or pretense to same’? And don’t I find you promoting sorcery your own silly self, Mister Magistrate Nickerson?”

“You—you wanted it.”

“Sure, did!. I wanted to see how much I could pin onto you. And if I needed any more—” Dobel’s voice rose to a virtuous bellow. “If that ain’t enough—don’t I find you here in your own house with a good-lookin’ brown girl?”

“Girl? … That girl?” stammered the unfortunate R.M. “Why, she’s a Mission girl. From Warange Mission. She came over tonight because her father was here. The chief—the Sorcerer— he’s her father!”

“Eyewash. D’ you think I can’t tell that kind? With her free-for-all ways? . . . Another one of your ‘native habits’ I suppose!”

Poor Nickerson. “You’re wrong. . . . On my honor!” This was what he gasped, and it deserves to live as a tribute to the female persuasion at large: “They only act so. It’s—it’s nothing against them. Only they can’t help themselves—some of ’em!”

Whereat Dobel did laugh.

“My colonial oath. Of all the soft sops! Wait till I tell that for headquarters!”

True enough, it was naive comedy close to grim tragedy again. True enough, it was Dobel’s entire triumph. He laughed. He straddled there, the hateful and conquering fellow, with his red grin directed over Nickerson’s shoulder toward the bead curtains. He finished his last drink. He stretched his great arms. “Well, that’ll do for entertainment. I’ll just be mooching along to my bungalow. … I’m taking that steamer tomorrow, you know. . . . Oh. I’ll be back. Yes, yes! Only I got to file my report, you see—the report that’s going to scupper y’r job for you, Mister Nonresident! Meanwhile, many thanks for the show.”

And he swaggered out.

Poor R.M. He was like a man overtaken in a nightmare. It was not so much the insult, the humiliation that had been put upon him. It was not even the inevitable loss of post and pay. What wrung him was his mistake—his failure to judge and to understand the given crisis: as every empire-builder should and must. Did such things really happen? They seemed incredible—far beyond any magic.

This was the ordeal of Nickerson. R.M., when he turned mechanically to attend again on his stricken performer—and found the place empty. The Sorcerer had vanished. . . .

Outside lay Papua, primitive and incalculable: Papua, where mystery and death wait on every move. What could he do? To be sure, he had two armed sentries at the station gate. To be sure, he might rouse the rest of his police from their barrack. What good would his handful be, against Papua? … A wind sighed in the swamps and the trees—heady as the essence of vitality— heavy as the scent of a slaughterhouse. From the cannibal camp just beyond his flimsy palisade the tom-tom kept throbbing: and his own pulse kept time with it. Nobody else could have listened with such agony for another sound—like the gather and snarl of a breaking wave. Nobody else could have visioned so vividly the horror that has overwhelmed and blotted in blood so many outposts. (In Papua.)

It was rather with some vague idea of finishing more or less on his own feet with his face in front that he reeled over toward the bead curtains of the verandah and peered through.

A dim glint of moonshine slanted across the parade ground and made visible its sandy strip. And more besides. Something curious, and curiously illuminated and illuminating. Over yonder, by the clump of croton bushes. Over yonder, near the guest bungalow: two figures, interlaced. One a great hulking white man who held clipped in his arms a native woman: the other the slim, thin-garmented native woman who clung quite willingly to the white man. . . .

Well, there are things which happen and there are things which are not done: the burden is in judging them aright even among strange and dark spaces. But in that flash that burden was lifted from Nickerson, R.M. For then he understood, at last. Then it dawned upon him—the real nature of his guest and enemy. Then it came clear, what he had failed to conceive: the wickedness rejecting all belief and all decency—the only actual power of darkness.

A gentle chap, kindly and mild and earnest to the verge of simplicity, so indeed he was, as hereinbefore stated. But then he remembered that he was the administrator responsible for Warange Station. Then he also remembered that he represented in his own person on the pay of a chimney-sweep the whole British Empire. And further, for the first time that night, he remembered the pistol strapped on his thigh! His hand fell to it. As if released with a steel spring in all his slight frame, he took a single jump over the verandah and out onto the parade-ground.

He was just too late. At the same instant Papua had chosen her own tragedy once more. An inky shape rose out of the croton bushes. A polished belt-axe gleamed in the moonlight. … A sweeping gesture—a choking cry—and a cloud closing swiftly as a wink.

When Nickerson reached them, the two figures were still interlaced more or less, though rather differently. The man could scarcely hold the woman, sinking from his paralyzed arms. It was Nickerson who received her as she fell, limp and voiceless. It was Nickerson unaided who carried her back the entire distance. Finally it was Nickerson who brought her into his house and laid her carefully on the mat beside his table.

She looked quite handsome, the good-looking native girl— under the lamp. But her fringed lashes were lowered with no provocation now, and her graceful copper-bronze body was now neither timid nor bold, only pitiful and elemental. . . . Nickerson knelt beside it. His hands never shook. His face never altered. He had the deft detachment of any trained surgeon as he made his examination, and straightened up.

“She’s dead.”

“Good God—!” stammered Dobel.

“I suggest you had better make sure of that fact yourself. . .

“How could—how could she be—?”

“Instantaneous, I think. A blow at the base of the skull. But I would ask you to verify.”

Dobel? . . . Dobel could verify nothing. The big, gross and swaggering fellow had gone like a punctured bladder of lard. He was all of a sop of terror: his joints sagging under him, the sweat steaming from his flabby cheeks and the eyes starting in his head. He tried to speak and made no more than whimpering noises in his thick throat.

Nickerson considered him, gauged him with one contemptuous scalpel glance and dismissed him from immediate mind. Nickerson had never been calmer in all his years of work. Icy and aloof, he stayed thinking, with the images and the measures of all his knowledge running clear—everything he had ever learned about his people—everything that had given him his control of cannibal and headhunter, wandering thief and fugitive murderer. And his thoughts followed somewhat along this line:

How had the Sorcerer escaped? To the right, into the crotons. What lay behind him? The palisade, surmountable, but sharp with spikes. What lay in front? The open parade-ground. And to the left—? The gate, and the only exit from Warange. . . . Meanwhile there had been no alarm, and the tom-tom was still drumming quietly outside. . . .

He shifted his pistol to his left hand. He edged with infinite precaution toward the verandah entrance. He poised silently by the curtains. From there, on a venture desperate as the last gasp of a swimmer—necessary as the last leap from under an avalanche—from there he launched himself into outer shadow. And . . . simply plucked forth the black crouching bulk he found in that exact concealment!

The Sorcerer had nothing much to remark: there is little even a Sorcerer can say with the muzzle of eternity pressing against his ear. He had nothing much to do except precisely as he was told: there is little else for anybody when he feels the oiled click of a large-sized automatic pistol jarring into his bones. Besides, as Nickerson explained to him (it was interesting how explicit and convincing the R.M. could be with that language)—besides, the plain choice was between one corpse and two corpses: life or death: just an ordinary matter for adjustment any hour and any minute in Papua.

So presently the Sorcerer was kneeling on the mat again, in the same spot under the lamplight, as before. And presently he had opened his bag of oddments and conjuring stuff, and had brought out a fragment of greenstone shaped like an arrowhead—as before. And presently, with the subject of his demonstration in proper position—very gently, very slowly—he began to stroke— precisely as before. . . . And thereafter the souls of two white men —watching—were drawn from their roots and whirled upward . . . were tossed and torn in a suspense almost intolerable . . . waiting . . . while they glimpsed the depths of lost and forgotten fantasies in the backward abysm of time. . . .

The garrison of Warange Station are a very smart drill. They have often proved it, and it does them credit, and they are rather swanky about it. They are only a handful of native police. But they have practiced the call to arms, even at midnight, until they can do it generally—starting on the unannounced toot of the whistle —in something close to two minutes. (Nickerson’s weekly reports are always meticulous in stating such details.) On this particular occasion it could hardly have been more than a few seconds over the two minutes when the little command stood ready.

The gates had been closed and the sentries doubled. Corporals Arigita and Sione had arrived one pace to the front. Behind them clicked to attention a rank of six privates—kilts, rifles and bandoliers complete. While Sergeant Bio, a prince of noncoms, stepped forward on the verandah before the wide-opened curtains in the lamplight, and saluted.

“Company under arms, Tabauda!”

The R.M. inspected them for a moment. They noticed nothing unusual about him. Except perhaps a certain added ring in his tone and a certain stiffening of his parade-ground manner as he snapped his orders.

What he said to the corporals was:

“Sione and Arigita—you see this fella black girl? You walk along with her one time to Mission House. You escort her safe and leave her there!” Whereat the corporals saluted, received their charge and tramped away, stolidly.

What he said to the sergeant was:

“Bio—you see this fella white man here? You take him and lock him in the lock-up. With irons if necessary. Tomorrow he goes by the coast-steamer. And he does not come back!” Whereat Bio saluted, fell in the prisoner between two guards, and started, smartly.

What the prisoner said, as he was led off nearly weeping, was: “Oh God—get me out of here! Take me away from this dam’ country. . . . Oh, take me away!”

What Nickerson said to the Sorcerer was little more than a formal apology, ceremoniously delivered, for events that had happened. But what the Sorcerer said to Nickerson in reply deserves to be recorded.

They were alone there in Nickerson’s house. The Sorcerer stood proud and inscrutable as a carven Assyrian statue—dignified as becomes a high chief and a master of magic and a gentleman in his own fashion, in Papua. And his answer substantially was this:

“Tabauda: nothing has happened. It has been a pleasant evening between friends. I am much honored by my visit. I am gratified if I have entertained you with my poor art. It is my hope that your days may be long in this land—and I would ask your lordly permission to depart!”

From outside in Papua somewhere there sounded the peaceful throbbing of a tom-tom. . . .

Host Commentary

Some notes from editor Shawn Garrett.

‘Because of colonialism, there are any number of “white men disbelieves native magic at his peril” stories – and most of them aren’t very good (for my money, “Pollock and The Porroh Man” by H.G. Wells is one of the best), following a straightline narrative and often casually racist (while intending the opposite effect). This is not one of those. Russell (who also wrote the quite brilliant “The Fourth Man”), here attempts to unpack a loaded scenario of privilege and power dynamics (who is beholden to whom?) while illustrating one of the uglier sides of colonialism, and while asking “what is the real ‘power of darkness’?’

With stories like this, just last like last week’s, we’re presented with an opportunity to see where we are and what distance if any we’ve travelled from the time depicted in the story. That’s an almost entirely intellectual exercise and that leads to my first realisation about this piece. I can see what it’s doing, and I find it interesting and subtle. But I don’t, at any point, care. That’s not to be read as a criticism, rather a visceral endorsement of how we interact with art. Emotional responses are a sign of connection. They aren’t the same land bridge as intellectual response although they do travel in the same direction.

That lack of emotional connection is also a luxury. I’m a college educated middle aged Caucasian man. The prejudices of both main characters in this story aren’t pointed at me. And what prejudices they are. This line:

‘It remains an active hell of heat, fever, violence and sudden death. In fact, it remains . . . Whenever a hard-working explorer casts about for some place to get lost and to write his next book, he considers Papua on the map and then goes somewhere else.’

Was the first to pull me up short. Not just because of the blistering, complacent cruelty that defines it but by how familiar it sounded. This sort of hyper articulate white guy sneering has been popular as long as white guys have had things to sneer at but right now, in 2025, on January 20th, the first thing this puts me in mind of is Jeremy Paxman’s decades-long career dedicated to showing us how many words he knows. The cruelty in this story isn’t pointed at me. But it’s expressed by people who look and sound like me and the only difference is, in 2025, they have twitter accounts and livestreams as well. That brings us to.

‘He was already sorry for it. He was due to be a great deal sorrier. . . .’

The truly evil bullies are your friends. They’re the ones who hop on the wall next to you and look at the next guy in line, comedically wincing with exaggerated sympathy as something bad happens. They’re the ones who claim they didn’t do anything wrong as someone bleeds. They’re the ones who always have the right excuse, say the right thing, make the right case. You want an example from real life? Aside from the one we’re all thinking of? When I was a kid, two other boys in my class bullied me mercilessly. Not physically, I could dribble one of them up and down like a basketball and hurt the other one as badly as he’d hurt me if it had come to that. They were snipers. Funny. Cruel. Picking away at me until I snapped and chased them and never quite ran fast enough. So, finally, I told a teacher and the three of us were brought in front of the headmaster. He asked them to explain themselves and they said they were worried about me because I was unfit and were making me chase them so I could lose weight.

The teacher let them off. And I found out that the sound of your respect in authority dying is a lot like the gentle sound of a balloon slowly deflating.

And then there’s this.

‘Through their meal together the two white men had been waited upon by Nickerson’s houseboys: rough-handed and half-tamed products of the cannibal frontier. But this was a girl! A girl, and the like of a girl to draw the bloodshot gaze of any Dobel, East or West. “What—ho!” he gurgled.

A native girl in a white man’s house?’

Look at the casual malicious use of language here. ‘rough-handed and half-tamed’, ‘cannibal frontier’, ‘A GIRL’. The men are subhuman and the women are irrelevant in every way besides exploitation. And from our modern perspective there’s the greasy sheen of the bounder, the likable rogue, peeling away in the heat as it sweats off these two monsters fighting over what a decorous level of evil is. ‘A native girl? In a white man’s house? IN THIS ECONOMY?’ Who could imagine such a thing? How naughty. How debauched. How cruel. How terrifying. And finally.

‘Mister Nonresident!’

The horror here is nothing but edges. The dehumanisation of the locals, the casual brutality, the casual sexism, the off-hand violence and last of all the realisation that there are no heroes here. One man commits murder. One man is so terrified all he can do is throw his reputation behind his fists and one is so cowardly he lets all this happen until he finally lashes out. He does this not out of mercy or of realisation of what they’ve done. He does this because standing over a dying woman’s body he finally has the upper hand. An upper hand defined itself by him finally finding someone new to hate. ‘

So, where’s the horror? Everywhere. But most of all in the realisation that this story was published a long time ago but, like last week’s piece, like Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, like so many of these narratives about white men breaking places that break them, it’s all too familiar.

And PseudoPod wants you to remember ‘It seemed to me that the house would collapse before I could escape, that the heavens would fall upon my head. But nothing happened. The heavens do not fall for such a trifle. Would they have fallen, I wonder, if I had rendered Kurtz that justice which was his due? Hadn’t he said he wanted only justice? But I couldn’t. I could not tell her. It would have been too dark—too dark altogether. . ‘

About the Author

John Russell

John Russell was an American writer and screenwriter. Russell wrote for the New York City News Association news agency, and then for the New York Tribune. He wrote the screenplay for Beau Geste and several other films. As author he was best known for his short stories, originally written for a wide range of magazines and newspapers, and then collected in books. He also wrote The Society Wolf, published in 1910, which was written under the pen name Luke Thrice.

About the Narrator

Maui Threv

Maui Threv was born in the swamps of south Georgia where he was orphaned as a child by a pack of wild dawgs. He was adopted by a family of gators who named him Maui Threv which in their language means mechanical frog music. He was taught the ways of swamp music and the moog synthesizer by a razorback and a panther. His own music has been featured over in episodes of Pseudopod. He provided music for the second episode ever released across the PseudoPod feed: Waiting up for Father. He also is responsible for the outro music for the Lavie Tidhar story Set Down This. He has expanded his sonic territory across all 100,000 watts of WREK in Atlanta where you can listen to the Mobius every Wednesday night. It is available to stream via the internet as well, and Threv never stops in the middle of a hoedown.