PseudoPod 947: Will They Disappear

Show Notes

From the author: “This piece is based on the horrendous real-life story of Jennifer and Sarah Hart, two white women who adopted six Black children and then proceeded to abuse them for years. (In a ghoulish twist, they brought their children to Black Lives Matter rallies.) At every turn, the Harts used their whiteness to shield themselves from consequences, even as the children tried many times to get help. Finally, when the Harts feared that they might face some accountability, they drugged their children with Benadryl and then drove their car off of a cliff, killing everyone inside. This story depicts much of that abuse, but with a very different ending. The women in my story get a tiny helping of what the real-life Harts so richly deserved.”

Will They Disappear

By Cynthia Gómez

I’m only fourteen and I don’t look like much and I’ve lived in more foster homes than I can count on two hands but I’ve learned a lot of lessons anyway. Like: playing dumb is a real smart strategy, most of the time. So is playing weak, only showing my strengths when it’s the right time. I didn’t do too good a job with that one, but if the names “Jessica and Elizabeth Love” ring a bell, then I think you might just forgive me.

I was different from the other kids in every foster home for a couple of reasons, but here’s the biggest one: I can make things disappear. No living things, even though I admit it, I did try. Just on a potato bug. I was kind of relieved it didn’t work, honestly. I can’t do it with anything big, like whole buildings, probably because there might be living things in them. It’s only little stuff, like making a homework assignment disappear so I could say I never got it, and one foster father’s keys I kept taking away because I knew he was cheating and … okay, maybe I did mean that one to hurt? The family thought I was stealing, and that’s how I got kicked out.

I can’t make them reappear. I also don’t know where they go. I didn’t used to care, but now that I’m older I keep imagining it. Are they all sitting in some back room somewhere, gathering dust? Are they dust? Also, when I wish something away, something else appears. I don’t know if they’re all coming out of the same funny place. I’ve never pictured a dark tunnel, a damp cave, the kind of places inhabited by trolls with hairy feet and green teeth. Instead I picture a store room somewhere, neat rows of shelves, the stock doors rolling up and down whenever new things appear. I think it’s because that’s what I really want. Everything in order, everything clean and bright. A long table with room for everyone I got attached to in all the homes I’ve been in. Everybody doing their chore—chop the lettuce, wash the dishes—and eating three meals every day. Someone to tuck us in and call us back if we left our dirty plate on the table. It’s what I thought I was getting when the Loves took me in.

I wonder if I spent a lot of time in an actual stock room when I was little. I have no idea: The records of my life begin when I was two. If you can believe the Stanislaus County Department of Social Services, they swung open the door of their office at exactly 9:01 in the morning and spotted two-year-old me, standing in the cold in a pink sweatsuit and sparkly shoes. Waiting patiently, happy to enjoy hot chocolate when they brought me inside. Newspaper articles, TV spots, my plump brown cheeks and pigtails smiling for the cameras, turned up nothing: no tearful mother regretting her choice to drop me off in the lot, no grateful family with throats hoarse from looking all night. Nobody could figure out how a child as well-cared for as me could just fall out of a family and not be missed. My clothes were clean and smelled of laundry soap; my skin was healthy, my hair shiny. When the social workers asked me to play a game of pattycake I indulged them, like that was a game I didn’t care for, thank you very much, but I would humor them just this once. I could suck up chocolate milk and hot chocolate like a fish, though, and they couldn’t figure out how I’d managed to eat three whole packages of Otis Spunkmeyer cookies in less than five minutes. They found me covered in crumbs, a look on my face like, “I was wondering when you’d show up.”

After weeks they realized they needed a birth certificate for me, because apparently you don’t exist without one, and no bureaucracy—there’s a word I learned early—can tolerate an un-birth-certificated child. One of the social workers, who apparently loved Greek myths, decided to name me Athena. She sprung full-grown from her father’s head one afternoon, which was as good an explanation as any for how I got there. After they talked to lawyers and experts and took way too many x-rays they decided I was somewhere between 24 and 26 months. They could write “unknown” for father and mother, but I still needed a birth date, so they stuck the year precisely two years before. The date was the same day I appeared at the edge of the parking lot, like I didn’t really exist in the world until someone official was there to see it.

Applications were flooding in to take in Baby Girl Moses, including of course lots of evangelical families, and I have to think that my brown skin was like an added bonus. Extra Jesus points for saving me not from the bulrushes but the acacia tree outside the front door.

I stayed with my first family for five years, until I was seven. I remember it mostly in colors, in feelings. Cookie dough spoons scraping the sides of a bowl, toast for breakfast every morning, tomato soup I couldn’t stand, scratchy grass in the backyard, the neighbor’s dog I snuck pieces of cheese to, pink tongue licking my hand through the bars. Wednesday night church service, already half asleep when we got home, my arms dangling over my foster father’s shoulders as he carried me inside and tucked me into bed. As far as I know, nothing ever disappeared there.

I don’t remember anyone explaining to me that I had to move on. I don’t remember anyone sitting me down and telling me that they’d got pregnant, a miracle they’d thought they’d never see. I don’t remember asking why I couldn’t just stay. I have to think that some conversation happened. That they didn’t just do what some adults actually thought helped: lying and telling me they were going to the store, and then never coming back. Oh, we’ll shield her from the panic. I have to think that they didn’t just quietly pack up my things and wave goodbye, tears in their eyes, sadness soothed by the swelling of her belly and the kicking of their new child through the skin. If the conversation did happen, did I just block it out?

It’s one thing to get a foster placement when you’re two and adorable and the story of Athena in the bulrushes is national news. It’s another when you’re seven and you’ve started wetting the bed for the first time, and you keep sneaking out the front door of wherever they send you, trying to find your way back to your home. I think it was three or four places I bounced back and forth from in two years, a damp little brown ball.

I remember the first thing I made disappear. It was harmless: All I had left on my plate was eggplant, eggplant I had to finish if I was going to get brownies for dessert. I stared at it and I wished it would just go away, and then I fell onto the floor and it was gone. I’ve since learned how to not fall. It makes me light-headed, like that feeling you get when you stand up after you’ve been sitting still too long. But I’d made a mistake, because the whole plate was gone too, and I couldn’t explain why. I didn’t get any brownies. And I also couldn’t explain why there was a pool noodle in the washing machine, in a house that had no pool anywhere near.

I went overboard at first, once I figured it out. Wouldn’t you? I made my dirty socks disappear, and later on that night with no warning a pair of ancient encyclopedias, from the 1980s at least, showed up inside the bathtub. I learned to wish away the eggplant—I don’t care who says they like eggplant, they’re lying—but not the plate it was on. But it was a gamble. I might make the eggplant disappear and then a little green frog would start hopping around the living room. Or I’d wish away my bratty foster brother’s favorite game cartridge and a dead orchid would crash onto the floor.

Sometimes what showed up was scary. When I made my teacher’s hat disappear, a spider crawled over my sandaled foot. A warning from the bright tunnel? Another time what showed up was a jar of formaldehyde, a word I knew because I read every entry in those encyclopedias (Volumes E and F.) I thought of frogs splayed out and ready for the scalpel, of the frog that hopped over the sofa. There was what looked like a floating candy heart in the jar, red and pickled and bobbing up and down.

When I was ten I began to see myself in books, sort of. I was in a home that locked us out until 6:30 when the mom got home from work, and so I spent hours every day at the library. You’d be amazed how many books you can read if you find a little corner and curl up for three hours straight, especially when the librarian starts conveniently walking by and leaving little piles like breadcrumbs. I read the one about the teenage girl who could move things with her mind and got revenge against the bullies. It was fun but it didn’t matter how long I tried to make the brownies across the room come my way; they weren’t interested. After I read the one about the little girl who could start fires I actually stood outside and stared at the dry grass for so long that I missed the recess bell. The other kids made fun of me for a month after that. A month is a long time when you’re ten.

When I was twelve I finally landed at a group home, the bottom of a drain I’d been circling for years. This home wasn’t as scary as the stories the other kids used to tell, but, even so, things started going missing every day. For the first time in my life I was openly cruel about it. The little girl who shared my room could barely see without her coke-bottle glasses, and I didn’t take those, but I did wish away a ratty old T-shirt. She’d said the shirt belonged to her mother, who was going to take her back as soon as she got out of jail. I wished the shirt away and the little girl’s colored pencils too, and that night in bed a catfish skeleton showed up at my feet, little bits of flesh still clinging to the bone. I was awake when it did, because I was listening to the little girl crying. I tossed the fish in the kitchen trash, risking a demerit because we weren’t allowed out of our beds after lights out, and after I washed my feet (risking one more) I tapped gently on the little girl’s shoulder and asked if she needed a hug. She nodded and I let her curl up against me, wetting my shirt with her tears. That morning a stuffed turtle showed up on top of the dresser and I handed it to the girl, who didn’t ask any questions about where it came from. That’s one of the great things about little kids: still young enough to believe in magic.

I learned something else then: It’s one thing to bend so easy that I can be mute at one house or stupid at another one, especially with adults who think they’re the same thing anyway. It’s another thing to let myself get mean to a scared little kid. I was mad that I had to teach myself this lesson, but I figured if I started getting mad about everything that’s happened to me, that would be a really long thread to pull, and I’d end up with just a mess of tangled threads in my lap, and guess who’d be cleaning it up?

It was maybe three months after the stuffed turtle, and I’d figured out that it was a mistake to let myself turn twelve without being adopted. Nobody wants an awkward older kid, no matter what famous story she has. So I couldn’t believe my luck when Jessica and Elizabeth Love showed up.

They came into the visiting room, patting my hand, flashing pictures of their ranch-style home in Modesto, of the five children who lived with them there, all either adopted or on their way to it. I tried not to let myself get excited at the pictures of the family, grinning and making chocolate-chip cookies, every picture tagged #rainbowtribe and #SavedbyLove.

“You’ve been through so much,” the blonder one of them said, slipping an arm around my neck, white teeth opening wide in a smile. Pink skin against my light brown. Their pearl-gray minivan came for me the next day, two weeks before Christmas.

It was just Jessica driving, and she put on some radio news show and barely said a word the whole time, and when we got to the house she left me to huff my bags up the driveway alone. I tiptoed through the open door, and I couldn’t have explained it just then, but I knew there was something wrong here. Like, deep wrong. Soaked into the wet bones of the house wrong.

There was a “Live Laugh Love” painting sticking out of one of the half-open boxes all over the room, and a rainbow afghan on the couch. The kids were all huddled around a huge coffee table in the living room, piles of books and a few tablets open in front of them, and Elizabeth told everybody to introduce themselves. Mai Anh (”we call her Maya,” the Loves assured me) was nine, the youngest, and then Dev, eleven years old, tall and skinny, who used crutches he’d decorated with Flaming Unicorn stickers. (”They’re a YouTube band,” he said, like I’d been born yesterday.) Isaiah and DeAndre were twins, both twelve like me, and they both waved and then turned back to their books. The oldest kid was their sister Sienna; she was fourteen but looked younger than me. Except for her eyes; those belonged to a thirty-year-old single mom. All those skin tones looked like a multicultural Crayola box, and my flesh was the missing shade in the bunch.

“Is school on Christmas break already?” I asked, already knowing the answer.

“Oh, we homeschool,” Jessica told me. That same smile, teeth wet and bone white.

I shared a room with Sienna and Mai Anh, and I waited until it was dark that night, the stars trying to shine through the blinds, before I opened my mouth. “Sienna, what’s the deal with them? I mean, the moms?” Sienna took so long to speak, I thought she was ignoring me.

“You’ll see.” I could hear Mai Anh’s quiet snores. “It’ll be okay for a while. And then you’ll see.”

I thought she was just trying to scare me. I saw what she meant, soon enough.

After morning lessons Elizabeth came out of the kitchen with boxes and bowls for the kids to make gingerbread houses. Sugar glaze for glue, M&Ms in neat little bowls on the table, plates of gum drops in pink and purple, tiny licorice sticks for the chimneys. I’d never actually made gingerbread houses before, so I thought it would be like those TV shows and commercials where kids gobbled up every other piece of candy while their moms swatted them and giggled. Here, I watched Isaiah drop a gumdrop on the table and Elizabeth’s eyes shot right to it. Under that blue gaze he picked up the candy and put it right on that little roof, like that was the only place it belonged.

Elizabeth was the one who wandered around in her Black Lives Matter shirt, holding her phone up high, updating the family’s Instagram page. When she called out for everyone to smile, five heads swiveled toward the camera, five sets of dead eyes lit up, five sets of teeth flashed open wide.

As soon as the last photo was done the kids all jumped up, like they’d been stuck with a pin, and started cleaning up the little bowls, vacuuming the sugar off the carpet, wiping the counters until they were shining and clean. Elizabeth walked over and took each beautiful house and tossed it straight into the trash. Dish soap drizzled over each one. “Just in case,” she said, and she was actually smiling.

I’m not going to tell everything I learned in those first few weeks. Not everything is good to talk about. I will say that it wasn’t so much what they did to us but what they took away. Didn’t make your bed? Miss breakfast. Fail a test from Teacher Jessica, especially if the reason was your stomach screaming at you after missing breakfast? Skip lunch. I started searching the house for little things I could disappear: a bath bead, a paper clip, a sock under the bed. I wanted to see if anything that appeared would be edible. Nothing ever was, and the night I couldn’t explain the shiny white mannequin head on my dresser, the Loves put me outside on the porch overnight with a nightlight and a sleeping bag. They lived at the end of a dead-end street, and we’d never seen any neighbors on either side. No one to notice, no one to help. I didn’t disappear anything for a long time after that.

We moved a lot, the rainbow tribe and our rulers. Partly because Elizabeth was a traveling med tech and she could stick a pin in a map and drag us all anywhere. But that’s not the only reason why. Just after New Year’s a social worker came and talked to the Loves on the porch. The rest of us leaned against the door to listen: something about Mai Anh’s family and a bunch of calls and letters going ignored, and some relative that had been trying to see her for two years. Mai Anh rocked back and forth, Sienna holding her tight. That night we heard the panicked voices from the Loves’ bedroom at the end of the house, shouting about credit card debt and foster care payments that might disappear. “And then what would we live on?” I heard Jessica scream. It was still dark when the Loves threw a bunch of boxes into our rooms and said we had half an hour to fill them. The van rattled away before it got light, and the other kids just stared out the windows like nothing had happened. I was the only one surprised.

“I don’t get my hopes up anymore,” said Sienna, when we got to the new place, twenty miles south of Reno. “They just move.” Sienna was counting the days until she could get out of there, and try to free at least her brothers as soon as she could. I added them up with her: one thousand, four hundred, and twenty-one days. It was impossible to imagine, like a book I read about a stairwell reaching high in the sky, disappearing into the clouds.

I think we were in Nevada for three or four months, and then Elizabeth got a job in Spokane. After Spokane it was Eugene, and by that time I’d learned from Sienna: Don’t bother to unpack.

Wherever we moved, a bunch of us would go find the library. DeAndre told the Loves that getting our library cards could be a cool ritual in a new place, and we could post the pictures, hashtagging them #librarylife. “Yeah, I love adventure stories,” he told me one day while we were walking on some street in Modesto, or maybe Spokane, our backpacks so heavy they were slowing us down. “But also, when I’m at the library, they leave me in peace.” DeAndre spoke like a cross between a kid and an 18th-century gentleman, like the Alexandre Dumas books he’d started to read. We would bring back comics for Dev, who read the Miles Morales Spider-Man books over and over until their spines nearly broke.

It was quiet for a while in Eugene. Jessica was teaching us how to make balloon piñatas out of paper mache, and the first few times I sat next to her and that bowl of slimy white strips I wanted to pour the whole thing over her head. But, like the library, those afternoons were little slices of peace. When we were done we took the paper mache-covered balloons and popped them, and the scratchy things kept their shape, but they were empty, hollow inside. Elizabeth propped us up for pictures, and she posted a long gushing post to Instagram. She tagged it #rainbowtribe and #outofnothing. And, of course, #savedbyLove. She sat at her phone, swelling up a little more every time a like or a heart popped up. The way she always did.

Then one day Dev fell and dislocated his shoulder. Maybe he said something to the doctor, or maybe that doctor noticed something the other ones never did, because a few days later a social worker came to the door. The Loves couldn’t sit close enough to hear us, but they sat where they could see her reactions, which was basically the same thing. I gave the right answers, the ones we’d memorized. We all did. I was sitting there wondering what the Loves might do to Dev, who’d sworn up and down he hadn’t said a thing.

And then, I don’t know why, but I disappeared Jessica’s Converse from the shoe cubby by the front door, while we were all in the living room. I’ve never figured out what made me start up again, why I listened to that wish when I’d pushed down so many of them before. I think it was Dev’s face, tight with fear, while Jessica was wearing her perfect smile. When she showed the social worker to the door the sneakers were missing but she had to act like nothing was wrong. I loved watching her expression, trying to keep that sticky sweetness she wore, her face dissolving and hardening again. I wondered if something rotten would show up again, or something beautiful. Instead it was kind of neither: an Amtrak time table from 1952, half the pages highlighted and dog-eared.

Watching her face felt so good that I disappeared their “Live Laugh Love” poster that night while we were all in our beds. I was half dreaming when their bedroom door opened, and the Loves both ran screaming out, and there was a bat, flapping and tangled in Elizabeth’s hair.

I knew I was making it worse, because they got meaner the more panicked they got. But it felt so good to rattle them, finally, after I’d held it in for so long. I disappeared their faded Obama T-shirts and Jessica’s signed Kamala Harris hoodie, and they knew none of us kids could have done it. The Loves kept their bedroom locked. The other kids were beginning to suspect something, but nobody had said anything to me yet. Instead they kept opening the Loves’ scars, the ones I never let heal. “Maybe you need more sleep, Moms,” Mai Anh started telling them. Her voice was sweet but she’d discovered James and the Giant Peach that year, and when the Loves couldn’t hear she’d call them Aunt Sponge and Aunt Spiker. Sienna would say, “It’s okay. I lose stuff too,” and there’d be a little smirk at the edge of her mouth.

We moved to Oakland a few months after I turned fourteen. It was the last move, though of course nobody knew that. The Loves must have gotten another letter, another phone call, a visit they hadn’t told us about. They stayed up late one night arguing when they thought we were asleep. Elizabeth was convinced that we should go back to the house where she grew up, and Jessica was trying to talk her out of it. Like that was going to work. “Babe, please. I don’t have the energy to fix it up and you’re going to be working. And that isn’t a good place to raise kids.”

Like they give a shit, Dev mouthed to me from the hallway where we crouched, listening. We’d gotten real good at communicating without sound.

“You’ll see. Oakland’s gotten so much better the last few years. Plus they can’t even hire social workers, never mind keeping them. We might finally have some peace.”

So again we packed up the van and drove eight hours to a huge house on Dover Street. The Loves had kicked the tenants out in a hurry and their stuff was still scattered in every room. Most of it went off to the dump, but there was a pile of books we passed around like it was Christmas, and a pair of roller skates that Isaiah rode all over the driveway, even after he scraped his knee raw.

The move to Oakland turned something over in me. Maybe it was the way the libraries were different, all the books I started hauling back to the house, kids with brown skin wielding magic against their oppressors. Maybe it was the murals in the neighborhood, fists of all colors raised in the air. Maybe it was just turning fourteen. But I started disappearing things all over that house. I didn’t care if they punished me, and I knew I should have been afraid of something even worse than the heart-looking thing in the jar, but I wasn’t. When the dead rat showed up in the medicine cabinet I grinned and then used a pair of tongs to throw it away. At dinner I served the Loves their corn with those same tongs, and then I dropped them on the floor so I’d have an excuse to wash them before I served anyone else.

I took Jessica’s keys, three times, right from the hook by the door, whenever she knew the kids couldn’t have done it. Elizabeth kept calling her scatterbrained, and I could see Jessica crumbling and crumbling, wondering if she really had lost her mind. One of the things that came back was a toy gingerbread house. It looked just like the ones we made at Christmas but never got to eat. When Elizabeth asked where it came from I blinked and told her, “I’ve always had this.” The other kids still didn’t know anything, not for sure, but they knew who to root against anyway. “Oh, yeah, Athena’s always had that,” everyone said.

That night, once it got quiet, Sienna turned to me. “So what’s the story with … you know?”

“You’ll see,” I answered, hoping she could hear the smile in my voice, hoping it didn’t sound like a smirk. And then I wished away one of my socks, no big deal. I was ready for whatever might show up, even though I’d never forgotten that night on the porch. (On Dover Street it was the attic, stuffed with junk that could look like anything in the dark.) Then the moonlight shone through the window on a glittering disco ball, and the two of us took turns holding it up to the light, letting it sparkle on our faces. We hid it in my laundry hamper and agreed not to tell the other kids, at least not yet. Secrets were nothing new to the rainbow tribe.

I told you I was making it worse, and I was. One night I insulted dinner and dropped my plate on the floor and looked right at them both, the expression on my face saying, “punish me.” I could see them casting bewildered eye signals at each other. I never broke the rules. But Elizabeth called me onto the back porch and she looked hesitant, for a second, because I didn’t look afraid. I turned away so she couldn’t see the wish on my face, and I heard the belt whistle through the air but it didn’t land. When I turned back, her empty hand was trembling and her face was the best thing I’d ever seen. It looked like what I’d actually made disappear were her bones, and she was crumbling to dust while I watched.

So when the Loves got meaner and meaner, taking away food for almost any excuse, I knew it was kind of my fault. And my fault that DeAndre showed up one afternoon with a bag of stuff for us: bread, peanut butter, those little oranges from Trader Joe’s. He’d made friends with the neighbors at the end of the block, and he’d told them we were low on food because his mothers were sick. I mean, I guess they were, if you think about it.

DeAndre said he wasn’t going to go back, because the neighbors might start asking too many questions. But he did, because it was food. And I guess somewhere in there the neighbors sniffed out that something was wrong. Or maybe Mai Anh’s family found the Loves again, now that we were back in California. Maybe both. Because a social worker came knocking again, and by then the Loves were both rattled and furious and arguing all the time. Maybe that’s why they panicked so bad. The social worker left her card on the door in the morning and by lunchtime we were all in the van.

Elizabeth told the kids she had a headache and we needed to sit and be quiet. But our faces were all flashing at each other that something was really wrong. It was Mai Anh who pointed to the empty spots in the van, like she was reminding us that nobody actually packed any boxes this time. But then Elizabeth pulled up at a Taco Bell and for the first time ever we could order whatever we wanted. It felt so good just to eat. Plus, all of us kids were so tired. Every time the Loves shouted at each other at night it kept us awake.

The Taco Bell was the one next to the beach, in Pacifica, and afterwards we all ran around on the sand. We were already in the van when Elizabeth went back inside, and came out again with a tray of something called Berry Freezes. Mine was bright blue, and it tasted way too sweet, but as I kept drinking I didn’t mind so much. I finished almost the whole thing, kind of weird when it didn’t have any chocolate.

The ocean stretched off to our right as they drove south. It was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen. The sun was shining over the waves and the van smelled of beach sand and salt. I actually fell asleep, and I came sort of awake when the van pulled into a parking lot, my mouth sticky with sugar and my thoughts swirly and far away, like the fog. The Loves were sitting there totally quiet, and my skin started almost itching, I was so sure something was off.

I kept my eyes shut, pretended I was still sleeping, and I heard the doors open and gravel crunching under their feet. Then I heard tinkling bells, the kind that stores use to announce a customer, and then I made myself count to twenty before I opened my eyes. Well, it was supposed to be twenty, but I got to thirteen and I couldn’t wait any more. I opened them a tiny sliver and I saw nothing but a little coffee shop/restaurant, and an empty parking lot, with one car that had to belong to the staff. I opened them a little more and all the kids were asleep, and just like the day I crossed over that doorstep I knew something was very, very wrong.

I closed my eyes again and I listened for those bells and I tried to think about what I could do. I could try to wake up the others, and then what would happen to them? Would it be worse than whatever was going to happen next? Trying to think was like trying to swim through an ice bath; every thought kept freezing up. Could I stumble into the coffee shop and beg them for help? And say what, exactly? I knew how fast Elizabeth and Jessica could turn, their little heads swiveling, their voices honey soft. Adolescence is so difficult; no, please don’t judge her; we just have to be patient with these flights of fancy. I think she’s having a really hard day. Mother in prison, you know.

Then I saw it sticking out from behind the driver’s seat. A crinkled CVS bag, and inside it two empty bottles of Benadryl. And then, lying on Jessica’s empty seat, were two empty bottles of gin.

The bells tinkled over the doorway.

I shut my eyes and put myself back into a sleeping pose, trying to remember if I’d been leaning against the window or stretched back in my seat. The door opened and I heard two bodies settle back in, and the smell of hot chocolate filled the van.

I tried to just keep breathing, the way I would if I was asleep, and I tried to make my thoughts come to me faster. Disappear something. Anything, begged part of my brain, and another part answered back: And then what? And another part was furious, skipping right past fear, because on top of everything else they’d done, the Loves knew how much I enjoyed hot chocolate. Topped with whipped cream. I think it was that anger that did it. Because it means I didn’t fall apart from what I heard next.

“You ready, babe?” Elizabeth’s voice sounded thick and slow.

“Yeah.” I think Jessica must have been turning, looking at us. “Will it hurt?”

“No. They’re already out. It’ll be just like going to sleep in the ocean.” And then a window rolled up.

Make them disappear, begged my brain. But that had never worked before. And Jessica’s keys had got “lost” so many times that she’d made the car ignition keyless. They wouldn’t care now if I took away anything else in the car either, even their hot chocolate they’d just got.

I thought of that hot chocolate, and those gingerbread houses, and all the food we never got to eat, and the bodies sleeping all around me (or maybe pretending to, just like me.) I thought of that emptiness, that hollow space inside both of these women. The one they kept trying to fill with hashtags and stories where they were the heroes, saving their little rainbow tribe.

And that’s when I knew what I wanted to do. Wherever I’d come from, bright storeroom, mossy bridge, outer space, I didn’t care. If there was any logic or reason, anyone or anything I could beg. I begged them to let me just do this. I wasn’t wishing away a living thing, not really. Just something that belonged to them. Something they needed. Not a breaking of the rules. Just a little wiggly loophole that maybe had always been there.

From one breath to the next, that’s how fast it worked.

I feel kind of sorry for the EMTs that came squealing into the parking lot, eleven minutes later, frantic from rushing as fast as they dared on Highway One. And then just as frantically bending over the two women’s bodies, their skin already turning gray. The electric paddles thudded over their bodies again and again, but no response. Of course, there was no hope, never had been, not thanks to me. But it’s not like I was going to tell them.

I don’t feel sorry for the sheriffs, though, or the detectives that pounced on the van full of brown children, all of us drugged and waiting for the uniforms to come to our rescue. The Benadryl made everything smeary and far away, and we all kept drifting even as the cops and then the social workers kept asking their endless questions. We didn’t answer them. We knew whose side they’d been on.

At one point I leaned over to Sienna and we took each other’s hands. “You can stop counting now,” I told her. I was hoping she wouldn’t ask me if I had anything to do with what had happened to the Loves. I don’t think I could have lied.

Another one I feel kind of sorry for is the coroner. That first one, trying to explain how not one but two women just under forty had dropped dead on a sunny afternoon. Good health, no underlying conditions, nothing in their systems but alcohol. No marks anywhere on their bodies. And then his scalpel prying open their flesh—god, I would give up my power in a second if I could have just been there to see it. Did he scream? Did he swear? Did he run to the phone on the wall or pick up the one in his pocket, shouting something like “you’d better get in here now”? I like to imagine the cameras clicking, eyes growing wide, as they pried open the chest cavity and they found it, the fist-sized thing that showed up in each woman’s chest when I made their beating hearts disappear.

Obsidian, the autopsy note said, in a file I stole from one of the reporters. I knew what obsidian was, thanks to the Stephen King book I’d read when I was hiding from the Loves in the library. Heavy and brittle, jagged edges poking into the women’s ribs. There were words, too, etched into each one. The coroners would have rinsed off the blood, watching everything they’d ever learned run down the drain with it. And then once the red liquid ran off, they would have held the black hearts up to the light to read it, Jessica and Elizabeth’s favorite phrase: “Live, Laugh, Love.”

Host Commentary

PseudoPod, Episode 947 for November 1st, 2024

“Will They Disappear” by Cynthia Gomez

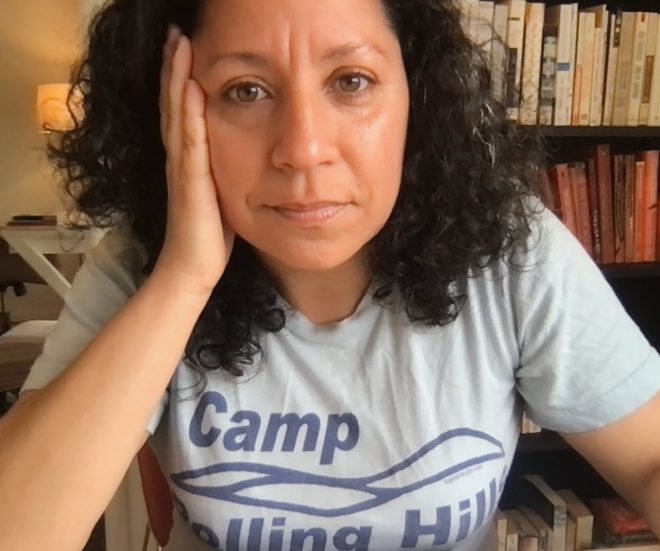

Narrated by Julia Rios, hosted by Eleanor R. Wood, audio by Chelsea Davis

Hey everyone, hope you’re all doing okay. I’m your host for this week, Eleanor R. Wood, visiting from over at PodCastle, where I’m Co-Editor and general dragon wrangler. I’m excited to tell you that for this week we have “Will They Disappear,” by Cynthia Gomez. This story first appeared in Cynthia’s collection The Nightmare Box and Other Stories, from Cursed Morsels Press, and I’m happy to say this episode opens our anthologies and collections showcase.

Cynthia Gómez writes horror and other types of speculative fiction, set primarily in Oakland, where she makes her home. She has a particular love for themes of revenge, retribution, and resistance to oppression, and she loves to write dark and frightening things while cuddling with her shadow, aka her adorable little dog. Her work has appeared or will appear in Fantasy Magazine, Strange Horizons, Luna Station Quarterly, Nightmare Magazine, and numerous anthologies. The Nightmare Box and Other Stories, her first collection, was released from Cursed Morsels Press in July 2024. You can find more of her work at cynthiasaysboo.wordpress.com.

Julia Rios is a queer, Latinx writer, editor, podcaster, and narrator whose fiction, non-fiction, and poetry have appeared in Latin American Literature Today, Lightspeed, and Goblin Fruit, among other places. Their editing work has won multiple awards including the Hugo Award. Julia is a co-host of This is Why We’re Like This, a podcast about how the movies we watch in childhood shape our lives, for better or for worse. They’ve narrated stories for Escape Pod, PodCastle, PseudoPod, and Cast of Wonders. Find them at juliarios.com or on Instagram as @zomgjulia.

And now we have a story for you, and we promise you, it’s true.

Well done, you’ve survived another story. What did you think of “Will They Disappear” by Cynthia Gomez? If you’re a Patreon subscriber, we encourage you to pop over to our Discord channel and tell us.

Here’s what Cynthia had to say about the story:

This piece is based on the horrendous real-life story of Jennifer and Sarah Hart, two white women who adopted six Black children and then proceeded to abuse them for years. (In a ghoulish twist, they brought their children to Black Lives Matter rallies.) At every turn, the Harts used their whiteness to shield themselves from consequences, even as the children tried many times to get help. Finally, when the Harts feared that they might face some accountability, they drugged their children with Benadryl and then drove their car off of a cliff, killing everyone inside. This story depicts much of that abuse, but with a very different ending. The women in my story get a tiny helping of what the real-life Harts so richly deserved.

Thank you, Cynthia, for the thoughts, and for writing this powerful story.

I am commenting on this story from the perspective of a white person undergoing the continual process of undoing internalised cultural prejudice. From that position of privilege, it really isn’t my place to dissect the racist themes running through both this story and the real-life events that inspired it, though I will say to my fellow white people: do fucking better. This is a horror story because of the truth running through it, and we need to look that truth right in its hideous, soulless eyes and condemn it soundly.

But there is another horrifying truth running through this one, and although it clearly intersects with the racism and white saviour complex on display here, it’s also a separate societal ill that affects virtually all of us. Social media can and does offer us all manner of benefits, but below the positives is a continuous, heaving mass of toxicity and harm. We can plaster over that with all the cat pictures and cute memes in the universe, but it’ll still be there, festering below the surface. So much of this story rests on the antagonists’ image, an image they’re able to carefully curate via social media manipulation. They’re feeding off social approval, leeching people’s empathy and compassion because they have absolutely none of their own. Social media provides an ideal forum for this kind of parasitic behaviour, and this tale serves as your regular reminder that you cannot and should not take people’s social media feeds as an accurate representation of who they are. We all curate them. We all post the things we want others to see. But every so often, behind the cute pictures and smiley façade, there’s something horrifying lurking. And there’s no way to tell if the feed you’re looking at is someone’s innocent projection or the glamour of a monster.

Onto the subject of subscribing and support: PseudoPod is funded by you, our listeners, and we’re formally a non-profit. One-time donations are gratefully received and much appreciated, but what really makes a difference is subscribing. A $5 monthly Patreon donation gives us more than just money; it gives us stability, reliability, dependability and a well-maintained tower from which to operate, and trust us, you want that as much as we do.

If you can, please go to pseudopod.org and sign up by clicking on “feed the pod”. If you have any questions about how to support EA and ways to give, please reach out to us at donations@escapeartists.net.

Those of you who already support us: thank you! We literally couldn’t do it without you! Anyone who’s thinking, ‘oh yes, I must go and do that,’ there’s something to be aware of: Apple have changed the way charging works through App Store apps. Long story short: sign up through a browser – including one actually ON your phone – and it’ll be cheaper than if you go through the official Patreon app. This doesn’t affect existing subscribers – don’t worry! – it’s just for new members.

If you can’t afford to support us financially, then please consider leaving reviews of our episodes, or generally talking about them on whichever form of social media you… can’t stay away from this week. We now have a Bluesky account and we’d love to see you there: find us at @pseudopod.org. If you like merch, you can also support us by buying hoodies, t-shirts and other bits and pieces from the Escape Artists Voidmerch store. The link is in various places, including our latest social media posts.

PseudoPod is part of the Escape Artists Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, and this episode is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Download and listen to the episode on any device you like, but don’t change it or sell it. Theme music is by permission of Anders Manga.

And finally, PseudoPod and Douglas Adams know….

There is a theory which states that if ever anyone discovers exactly what the Universe is for and why it is here, it will instantly disappear and be replaced by something even more bizarre and inexplicable. There is another theory which states that this has already happened.

See you soon, folks, take care, stay safe.

About the Author

Cynthia Gómez

Cynthia Gómez writes horror and other types of speculative fiction, set primarily in Oakland, where she makes her home. She has a particular love for themes of revenge, retribution, and resistance to oppression, and she loves to write dark and frightening things while cuddling with her shadow, aka her adorable little dog. Her work has appeared or will appear in Fantasy Magazine, Strange Horizons, Luna Station Quarterly, Nightmare Magazine, and numerous anthologies. The Nightmare Box and Other Stories, her first collection, was released from Cursed Morsels Press in July 2024. You can find more of her work at cynthiasaysboo.wordpress.com.

About the Narrator

Julia Rios

Julia Rios (they/them) is a queer, Latinx writer, editor, podcaster, and narrator whose fiction, non-fiction, and poetry have appeared in Latin American Literature Today, Lightspeed, and Goblin Fruit, among other places. Their editing work has won multiple awards including the Hugo Award. They’ve narrated stories for Escape Pod, Podcastle, Pseudopod, and Cast of Wonders. Find them at juliarios.com or on Instagram as @zomgjulia