PseudoPod 899: Arcanum Miskatonica

Show Notes

From the editors: The Nameless Songs of Zadok Allen & Other Things that Should Not Be is JayHenge’s 20th speculative fiction anthology, and editor Jessica Augustsson and her team had so much fun putting it together. She says, “ There were so many brilliant submissions, and we were lucky enough to be able to get a foreword by Elena Tchougounova-Paulsen, the editor of Lovecraftian Proceedings, a journal on academic Lovecraftiana. Mike Adamson’s work can be found in several other JayHenge anthologies, along with so many truly wonderful writers. We’re very excited to get even more eyes (and ears) on their work!

Arcanum Miskatonica

by Mike Adamson

Every university has its reputation—some for solid, middle-of-the- road studies in business, medicine, law, others for scientific research, and hopefully all for excellence. But some have shadows behind their ivy-grown cloisters, dusty corners where past mysteries linger, and some secrets are guarded, not merely jealously, but fanatically. I came to Miskatonic University, in the green hills above Arhkam, Massachusetts, as an eager research assistant for the School of Biology, specializing in molecular genetics. I qualified at Brown in my native Rhode Island, but an unfortunate road accident headed off a placement with a commercial research firm, and when I was once more fit to walk unaided, the most promising berth for my talents was with the laboratories of a competing college. A job was a job, and it was time for my career to blossom—a few years solid research in an academic setting was no bad thing, and should propel me into Big Pharma in due course. My parents, at home in Providence, were entirely supportive, though I recall my father speaking in what I felt a strange manner, the evening before I left. “It’s a fine institution, certainly,” he said, nodding into the gathering twilight off the porch, as the first leaves were turning, the drift of red and gold beginning their rain, though summer’s warmth was not yet a memory. “Do be careful, Rick… I know you are, but… They tell strange tales of that university.” He smiled and shrugged, as if dismissing his own disquiet. “It’s a 19th century classic—and has hosted every sort from the brilliant to the lunatic. It’s whispered their collections feature things science has never yet properly understood, and for the most part are buried away so as not to disturb modern thinking.”

I could only smile and assure my father of my caution, but his words stayed with me the next day, when the family saw me off at the station. I rode Amtrak north to Boston, then south down the coast and a change to regional services, and as the glorious colors of an early New England fall rolled by, I could scarce credit my father’s apprehensions. Stories were just stories, after all, and in this old, old corner of the United States, where standing structures from the 1600s were still to be found, stories were the very fabric of a folk melange which helped define its people. Little did I imagine, as I first walked the august halls of an institution in which one could quite literally smell the dust of antiquity, I would come face to face with the very quintessence of my father’s vague misgivings.

Bright lights and computers, the internet and massive display screens, I rapidly discovered, were window dressing—a superficial skin hiding something much older, and when I found myself in the cloisters I had to stop, smell the fall air, and listen to the wind in the dark woods that soared away toward the clouds behind the brownstone buildings, here on the slopes of the Arkham Valley. There was antiquity here, from the dignified solidarity of the university’s columns and pillars to the ancient remnants of colonial times in the nearby township of Arkham. Here, it was well known, 17th century architecture persisted, and a hundred years ago, many a damp and creaking relic had still reared its gambrel roof above the narrow streets.

Some people are more sensitive than others, and I had not been in residence long before I envied the students. The undergrads, wrapped in the pablum of the 21st century—their mobile phones, fashions and cliques, their tablets and laptops, tastes in music and television—were much the same here as in any institution of higher learning, yet, more than in any other I had visited, they seemed an ill graft upon a careworn stem. They were closed in upon themselves, brought their conception of reality with them, and in doing so, erected their veneer over the timeless and implacable realities embodied in the stones and beams among which they studied. Miskatonic had turned out excellent graduates from a dozen schools and departments, yet, if truth be told, not a single one left its hallowed halls without an appreciation for the shuddery things unspoken—unspeakable—about their alma mater. Therein lay my envy for the freshmen, for they had yet to be touched by what lay beneath the surface. Sophomores, it seemed, developed a hint, some shadow around the eyes, that told the observant they had walked where some, at least, would rather not.

I was a year there, busy with projects, when those strange, shadowy things made themselves plain to me. I was with a team working on cell membrane permeability in transitional cellular states, particularly stem cells as they differentiated, and had buried myself deeply enough in the job to have escaped the general air of strangeness permeating the older parts of campus. But all I had avoided came upon me without fanfare one morning as I sorted through specimens in the basement archive of the School of Biological Sciences.

Far from the third-floor laboratories, visibly modern with their plastic and chrome, LED lighting, computers, and fume hoods, I worked in a storage room which it seemed had not been opened in generations. The light switches were of a pattern at least seventy years out of date, the neon fittings overhead dated from the sixties, and the shelves over which they gleamed were tall and of massive timber and metal construction, thick with dust. I wrinkled my nose as I swept the dirt of ages away from sealed glass vessels in which floated all manner of biotic obscura. I read the labels with a curious squint, following the handwriting of ages past. Here a preserved deep-sea hagfish, revolting in its worm-like visage, jawless, with seven gill holes; there the gnarled fist-like shape of an armored marine arthropod; and again, a jar filled with bizarre insects, labeled as having rained from the sky during a storm in 1898…

Truly there were academic curiosities here, and my assignment was to re-catalogue them so the department could better evaluate the potential treasures amongst its older collections. But the penalty of time is that things which might have been better kept under lock and key tend to come to light in the least expected places.

It was a jar around a liter in capacity, the preserving fluid a golden yellow, and of curious contents—merely a glob of rubbery tissue of pinkish, almost gelid appearance. The label I read with some difficulty, turning the jar to the light with reverent care in my latex- gloved hands. “Unidentified tissue sample,” I read haltingly, “recovered from Lake’s camp 76°15’ S, 113°10’ E, January 26th, 1931. Reference MAE-Opus 23.” I blinked and as the tissue in the jar rolled a little, I felt a sudden revulsion. I set it down carefully and stared at it, trying to be objective—I had handled plenty of disgusting specimens in my time as a biologist, why should this be any different?

Obviously, the geographic coordinates placed the site in Antarctica. I drew my tablet to me and tapped in the reference number, but after a moment the university database flashed back a bald and somewhat intimidating message. Restricted. Departmental authorization required; see senior technical librarian for Opus 23 access.

Stranger and stranger… If it was restricted, why leave a sample among the standard biological teaching collection of years gone by?

An oversight?

I pondered a while, staring at the flabby mass in the jar, and was seized with a curiosity which, though I did not recognize it at the time, was almost unhealthy in its intensity. What could it possibly be? If the biochemists of 1931 had failed to identify it, then perhaps we should be dotting their i’s and crossing their t’s. Modern genetic assay techniques should resolve the mystery promptly; and I was fascinated to know what sort of creature could be found on the icecap anyway. I pulled up my departmental email app and dashed off a note to my team leader, requesting authorization to consult the mysterious Opus 23.

Silas Moriarty was the librarian in question and an appointment had been easily enough obtained. His office was hidden away in the older parts of the Miskatonic Library, an imposing building of quarried stone in the art deco style of the Thirties, designed to mimic antiquity, and thoughts of Egypt and Babylon crossed my mind as I ascended the steps to tall, brass-bound doors. First semester’s blustery fall weather had filled the byways with a russet carpet and ornamental trees were rapidly denuding as the year turned, a melancholy season to be pursuing mysteries of old. The library’s modern computing facilities, recharge points, research and general access terminals were a softly glowing spiderweb of information-flow that defied the age of the building with notions of modernity; but I passed the new, glass-walled cluster-offices of the subject liaison librarians and made my way along a corridor that led deep into spaces the students never saw, and I at last came to an office no less antique than its owner.

Gold-leaf lettering on a frosted glass door announced the Senior Technical Librarian, and I knocked, heard a gruff acknowledgement, and entered. The office seemed little changed from its origins, with tall timber bookcases crammed with document folders, an ancient reshelving trolley piled with unfiled folios, and unidentified paperwork on every horizontal space. A desk terminal and cordless phone were the only concessions to the new century, and I could believe I was in the presence of the past with a single look at Mr Moriarty.

He dressed from some traditional gentlemen’s haberdashers; I had no idea you could still get pre-war braces, and the hat on his coat rack would have made Indiana Jones feel at home. A bow tie added a period touch, and he was camp enough to have leather patches on the elbows of a tweed jacket. But the face, the face… Wrinkles were elevated to an artform, and eyes that blazed like dark coals were set in a maze of lines, topped with brows straggling like some indomesticate weed. The nose betrayed a love of drink, while lips, jowls and neck told me this senior-most position among the library’s curatorial staff had known a single occupant perhaps since the job was first described.

“I’m 105,” Moriarty grunted, as if reading my mind. “I was a Freshman here the year those ships left for Antarctica, Mr Coleman.” He stretched out a liver-spotted hand, the fingers crooked with arthritis, and I presented my written authorization without a word. He looked at it through bottle-glass lenses, then filed it peremptorily on a spike. “And what exactly is your interest in the records of the expedition?”

“I need to know the circumstances under which a tissue sample was gathered.”

“Tissue?” Moriarty froze for long moments. “What are you talking about?”

I quickly filled him in on my discovery. “If we’re to properly understand what we have, we’d like benefit of the expedition paperwork, which appears to be held in confidence here. The mere fact we need authorization to look it up makes us wonder what the hell we have hold of.”

“As it should. Where is this specimen?”

“Safely locked away,” I replied blandly.

The ancient regarded me as if I was some just-germinated seedling for a while, then fumbled in a pocket for keys. “Well, your authority is in order. I suppose I’d better show you what you’re here for.”

The sub-basements were more extensive than I would have guessed. An ancient elevator that stank of hydraulic fluids—palmprint released, despite its antiquity—took us down two levels to a corridor of marble and brass whose lights had not been updated in half a century. I could not find my voice and abruptly felt my scientific ardor was misplaced—what good could possibly come of explorations in a place so oppressive?

Moriarty walked with a cane, leaning on it quite heavily, and the strike of the ferule upon the tiles counterpointed his heavy breathing as we moved in the glow of incandescent globes. It seemed this part of the university had been overlooked by the upgrade programs. At the end was a double door of solid timber bound in brass, and the old man fumbled with the keys to locate one little used. At last, the heavy lock turned with a clash unnaturally loud in the chill silence, and the doors went back to reveal a lobby around which were several more doors.

“This is our most secure storage facility,” he explained with a note of pride. “Researchers have been coming here since the 19th century to consult our most prized possessions. You join an elite group, Mr Coleman.” He flicked on the lights with a dry snap and nodded to a door on the right. “There’s a very rare book behind that one.” He next gestured left. “The most important records of the Miskatonic University Antarctica Expedition of 1930-31 were placed in keeping here because the accounts and photographs are too contentious for general dissemination. You’re familiar with the official history, of course?”

I nodded readily. “I took the opportunity to read the public records before coming down to see you.”

“Then you will be aware certain events remain unexplained.”

“Lake’s camp was obliterated by a storm sweeping over a mountain range, and when the relief plane got there. Not a living thing remained.”

“Correct. The assumption has always been that in the extremis of their ordeal, navigation errors occurred, or errors of record, because it is known today no such mountain range exists, certainly not at the coordinates they assert.” He set a key to the lock and it turned grudgingly. “What you are about to read is the actual report made by the relief expedition, which will place in context the sample you found. It should have been stored here, with the rest.” The door went back, and I sensed his reluctance to release the information at all. “You understand you are bound by the confidentiality clauses of the contract you signed with the university when you took up employment? When I say this information goes no further than your eyes, and those of your supervisor if necessary, you may take it as gospel and law.”

I nodded my assent mutely, flesh creeping as I took in the tall bookcases and storage shelves, and wrinkled my nose at the smell of the place. Lights flicked on and I realized I was looking at materials from the expedition itself—logbooks, charts, boxes of paraphernalia, navigational instruments, manifests.

“It’s all here,” Moriarty replied, again sensing my thoughts. “Other than elements in the University museum, such as garments worn by the polar explorers, a dog-sled, and the majority of the general photographic archive. The rest is here.” He went to a shelf, tapped a metal chest, and asked me to place it on the table central to the room, which I did with some effort, then he set a key to its padlock and lifted back the lid. Revealed were leather-bound journals cracked with age and exposure to harsh elements, and alongside them, incongruously, boxes of mounted transparencies of much later vintage. “The original negative and positive film is stored under special conditions. These are duplicates made in the 1970s.” He drew out a heavy envelope and placed it carefully on the bench. “This is the photographic record of the exploration of Lake’s camp.”

He drew out a seat for me and could not help letting a small, sly smile break through. “I’ll return in a couple of hours and see how you’re getting on.”

The afternoon air was sweet in my nose as I took a seat on a bench beside a gravel walk between lawns and flower beds. I felt faint, and cradled a plastic cup of coffee from a catering wagon, sipping the hot, bitter brew without tasting it.

My world had overturned as I read the records, viewed the prints, and I was processing as well as I could a flood of information I abruptly would have rather not known. The sample in our laboratory safe now seemed sinister, and part of me was more than willing to deliver it to Mr Moriarty to be added to the archive and once more forgotten. But my curiosity as a scientist would not be denied and I warred with my conscience. Clearly, a period of a full day had elapsed after the exploration of Lake’s camp by the relief team, during which something else had happened, but records of that phase were in a separate container, not open to me.

The samples, the samples. The fossilized remains brought up from the aquifer Lake’s team had drilled into—non-permineralized specimens were themselves exceedingly rare, but their strange distribution after the storm had gone through defied understanding. Some missing, others buried upright in pits. Every man and dog dead, one team member missing. The tissue sample we possessed had been found on the sharp metal corner of a work bench, as if some creature had passed by in a hurry and injured itself. But everything in the camp had been in utter disarray, tents wrecked and flapping in the wind, containers broken open, contents scattered. It defied understanding. Had there been an explosion, the fuel reserves for generators and the expedition’s Fokker ski-planes, the damage patterns would have been very different. It was as if the camp had been rifled, deliberately but randomly —yet they were thousands of miles from the nearest human being.

Eighty-six years ago, explorers from this very institution had encountered something so utterly unknown, it seemed their findings had been suppressed—at the very least sanitized for public consumption. I had poured over the logs kept scrupulously by the scientists, reviewed Lake’s wireless reports to basecamp, of drilling into the dry aquifer beneath thin ice on the buried slopes of a cyclopean mountain range, and the treasure of fossil life it contained. These findings in themselves should have changed human understanding of the course of evolution; that they had not I could only attribute to the bizarre circumstances to follow, which even now remained a mystery to me.

Which left me with the specimen.

Well, I was a molecular biologist and I had my job to do. At the very least I would identify the creature from which the tissue came—I could do no less, and, very probably, no more.

Dave Tremont was my team leader and I took him aside to more fully explain the authorization he had dashed off for me. A sandy-haired ex-serviceman, he had come to science as a second career and found his forte in cell biology; he was solid and dependable, his calmness welding his people together. Thus his scepticism when I spoke of the bizarre events in the far south, yet the tangible evidence of the flesh in the jar was at least something with which we could come to grips, and he too was bitten by the curiosity to lay this particular ghost to rest.

“I’m not getting involved with speculation as to the sanity of the explorers who came back,” he said with an offhanded gesture to warn me clear of that topic. “We can only deal with facts, and our object must be limited to identification of the species. What could have been up there on the icecap, several hundred miles from the nearest coast, to injure itself?”

“You’re authorizing me to proceed?” I asked, a little stiffly.

He spread his big hands and pulled on his rumpled lab coat. “I’ll give you a hand.”

Specimens preserved in alcohol are subtly damaged at the molecular level, but still readable. The first step was to extract the tissue and prepare a sample. We used full barrier precautions, working in the biohazard chamber, to unseal the jar and lift out the tissue, then photograph it from all angles, beginning a new experimental log. The mass seemed homogenous, as if torn from a single, common tissue type; I prepared out a series of slides for microscopic examination, including chemical staining to reveal chromosomes. Iodine, crystal violet, methylene blue and other stains would give us a good range of possibilities. I lined up a dozen more micro-fragments to serve in further investigations, and was formlessly glad to return the glob of tissue to its container at last.

The jar was resealed with Parafilm, and placed in a safe chamber, bathed in ultraviolet light to maintain a sterile environment. The bench was swabbed down with 90% ethanol and all equipment sterilized the same way. I was aware we were being ultra-cautious, treating it as though the specimen were living tissue. We had no reason to assume it was, but where the unknown is concerned, the biologist has a duty to be careful.

The first slide went under the light microscope, I brought up the view on a slaved monitor, and at once our brows furrowed. “What the hell kind of cells are they.?” I heard my boss muse. They were of irregular shape and seemed to follow no specific pattern, while the interstitial spaces varied in width and seemed filled with a gelatinous substance. “Not muscle, not adipose.” We stared at the photographs of the sample on another monitor and could only shrug. It was not fibrous, not the sheet-form of connective tissue, and the microscope revealed no filamentary proteins.

I tracked around in the sectioned sample and as far as it extended the tissue was homogenous. “No nutritive or neural channels, not even capillaries,” I murmured. “It seems almost.” “Progenerative?”

I glanced up at Tremont. “I didn’t want to put it that way, but the lack of differentiation suggests a neotonous state.”

Neotony—the retention of larval characteristics into adulthood— was a concept best exemplified by stem cells: by definition, any adult tissue was already fully differentiated and could not, or should not, be in a precursive state. A neotonous organism, such as the axolotl, the giant salamander of South America, was defined as such because it carried foetal characteristics—external gills—into the mature form, not because its tissues were embryonic. These cells, however, seemed uncertain what they were meant to be, yet had evidently come from a fully competent, highly mobile organism capable of surviving extreme environments—by all definitions, an adult.

We could only shake our heads, and I switched to the stained slides. The nuclei were tight and dark and I closed in on them, tracking gently in search of dividing cells in which chromatin had developed. The majority of cells were in interphase, the so called “resting” state in which the cells performed their tissue function, but a small proportion would be undergoing mitosis—division—at any one time, and I was looking for a cell fixed at the moment its chromosomes were clearly separated.

When I found one, we could again only gape. The number of chromosomes was difficult to distinguish on this or any of the slides, but our best estimates did not match any known Antarctic species— which were, after all, limited to marine and avian types as there are no purely terrestrial animals native to the polar region.

Tremont scowled and nodded to the gene sequencer array in the next laboratory. “Let’s stop screwing around. Sequence this sucker.”

By evening we had our next mystery. The sample prepared for the sequencer was treated, separated, washed, all the steps of chemical analysis leading to the actual reading of DNA, and when the machine began to compile the genes of a single chromosome, we puzzled openly. Masses of unspecific DNA—introns —characterized most of it, as if the information were itself loosely organized.

“It’s as if it spells nothing at all,” I mused, rubbing my eyes and pouring more coffee. We were out of our environment suits, the biohazard lab was sealed at this time.

“Or.” Tremont scowled, forcing his thoughts. “Or, that these genes code for many potential things.” At my expression he warmed to his theme. “This is a library of information, waiting to be accessed.”

“Precursor code.” I snorted a sigh. “That would fit the neotony model, but leaves us again with the question of how a mature organism can have embryonic tissues.”

He threw up his hands, looked around to ensure we were alone and lowered his voice. “What we’re seeing even now rules out any animal in the database.”

I nodded with a helpless expression. “The question is, do we continue, or do we run it by the ethics committee for guidance? If we’ve no real clue what we’re dealing with, does oversight come into play?”

Tremont slugged down coffee and stared at the data displays as the sequencer continued its massive through-put, wading through the creature’s incomprehensible genome. “I’m not sure. I doubt today’s committee will have any better idea than we do of the facts of 1931. And we’re in the best position to obtain any facts willing to yield to analysis.”

“Old Moriarty seemed to know a lot more than he was telling.”

“A librarian? Well, he’s old as god. And he’s been the keeper of that archive since long before any of us was born.”

“He knows it all, the good, the bad and the unacceptable.”

Tremont seemed to agree but another line of thought distracted him and he tapped the screen, thinking aloud. “I wonder. These codings are very complex, and we’ve got a lot of superimposition in the strand bundles. An input of energy might clarify things for a second run.”

“You mean laser excitation?” A micro-fine burst of laser light was used by some techniques to help sort and separate DNA masses. “It’s worth a try.” I began to prep a fresh sample from the microslivers on standby, as Tremont prepared the equipment, and the first run was coming to an end by the time we had the next ready. We reset the sequencer, but I felt a strange crawling in my spine as the sample was subjected to excitation. It should merely provide free- energy-of-activation for the suspended chemical processes, allow the complex compounds to interact and hopefully line up in ways more clearly interpreted, but something about it gave me the creeps.

It went into the machine and began its run, and I raised my eyebrows at the boss in forced good humor as I pulled out my mobile to order us supper. It was going to be a long evening.

Arkham Pizza did an excellent supreme, and we were done by the time the results were compiling. We began to see the same sort of sequences as before, but the machine was reading them more easily, racing through the compilation, and on a whim, I brought up the results from the first run and launched a comparison routine. The cross-matching program began to find sequences in common, confirming we were getting a clean “read” on the material. But soon we began to spot a number of anomalies.

“Variation,” Tremont mused. “Sequences very like those read the first time, but which seem to have undergone base-pair substitution.”

“Mutation?” I exclaimed. “It would be rare for an excitatory pulse to cause that. Very rare.”

“It would be no use as a sequencing tool if it did,” the boss mused, shaking his head as more divergences appeared. “It’s almost as if…” He trailed off, and his face clouded, he would say no more, but took one of the spare slides and subjected it to an excitatory burst, then lay it on the bench under a full-frequency lamp. Our eyes met but I said nothing, feeling my flesh creep at the implications, and ten minutes later he stained the specimen with crystal violet and put it under the light-microscope. 400 x magnification brought the cells into sharp relief, and he tracked the image gently.

We gasped.

The number of cells undergoing mitosis was many times the expected proportion, and the further we looked, the more cells we found reorganized at prophase, the beginning of the divisional cycle. It was as if the energy had provoked a systematic response.

Tremont stepped back from the instruments, his expression bewildered. “This tissue is alive,” he whispered.

“After 86 years in alcohol?!” I exclaimed.

“Look at it!” he barked. “The cells are dividing! That’s why we’re getting anomalous deviation on the second run, the DNA is transcribing—and unless I miss my guess, those unspecific cells will have decided what they’re meant to be.”

“And are in process of becoming…”

Tremont tugged out his mobile and used the university staff database to locate old Silas Moriarty. Getting through took time but when he heard the crusty voice, Tremont laid out the situation. “Mr Moriarty, I don’t want to hear anything about jurisdiction and chains of accountability. We have a situation and are dangerously close to playing with fire. We need to know what you know. I’m going to have campus security send a car to your home, they’re going to bring you directly to the genomics lab, and you are going to tell us the whole truth.”

I distinctly heard his words in the air. “You might not like it.”

“I’m beyond caring. Right now I need to know what to do, and you’re going to guide me.” He hung up and called security, then we sat tight, staring at the dividing cells on the monitor. It was almost mesmeric, especially the speed with which it was happening. Human cells generally took about an hour to complete a division, but we watched cells under the lenses complete a replication in less than ten minutes. With a trembling hand, Tremont added drops of culture medium to the slide, preventing it drying out in the heat of the illumination source, and we saw divisional rate jump again as the cells received builder nutrients. Maybe that was the wrong thing to do, because the tissue fragment had increased its mass by a factor of sixteen by the time security called to say they were on their way up with the librarian.

Most of the staff had called it a day by now, the campus was floodlit in the fall evening, and we saw amber flashing lights as security arrived below the block. They had brought a collapsible wheelchair for the old man and had him into the elevator in moments. We were waiting in the corridor when they appeared, and Tremont asked them to stay within earshot. I wheeled old Moriarty into the glare of the lab lights and he folded his hands defensively on the stick across his lap.

“What have you done?” he asked bluntly, more than a hint of fear clouding his rheumy old eyes.

“Our jobs,” the boss answered for me. “We’re trying to identify what species that tissue came from, but we can’t. It behaves like nothing we’ve encountered before. We need to know if we are at risk.”

“Do you have reason to suspect it?”

I stabbed a finger at the screen. “Given that tissue collected in Antarctica in 1931 is presently growing, we have a right to be concerned.”

The old librarian blanched, his words failed him; he stuttered and pressed a hand to his mouth. “You fools,” was all he could murmur at first, then looked up, eyes blazing. “Why can’t you people ever leave well alone? This was all safely contained, a cycle of events which ran their course long ago.” He passed a hand across his face. “You must destroy it.”

“Destroy it?” Tremont narrowed his eyes, and I felt the same indignation. “This could be one of the most important discoveries of all time!”

“Damn your discoveries!” he barked, slamming his stick on the arms of the chair. He wagged a finger. “Now, you two whippersnappers are going to be quiet and listen!”

We shared a glance of apprehension, but he had our undivided attention.

He closed his eyes for a difficult moment. His voice was careworn, his century-plus heavy upon him. “The 1930-31 expedition found strange and terrible things. Things we can’t relocate today, but we have their records. That sample should never have been stored separately! Clearly, the danger was not appreciated.” He seemed lost, kept glancing at the monitor, the slow but steady division mesmeric. “When Professor Lake drilled into that aquifer he set in motion his own doom, because he uncovered not just evidence of past life, but surviving life.”

We did not interrupt, but a chill crept up our spines. I abruptly wondered what horrors were related in the cases which remained locked…

“Two of the expedition members—the leader, geology Professor William Dyer, and a grad student named Danforth— stripped one of the planes and crossed the range. On the far side was a plateau, and on it was.was.” He had to grit it out. “A city. Like nothing else on this Earth. They landed and explored, they were sixteen hours in its haunted halls, and they recorded everything they could, to the limit of their film and paper.” He seemed ill, his color poor, and I began to fear he would expire on the spot. Through dark-tinged lips he forced out the words. “It was the last bastion of a race old beyond imagining, the first colonists to reach our Earth in the distant past. and not as extinct as they first appeared. The confused account of Dyer and Danforth’s last hours in the city makes it clear the explorers were not alone. It would seem eight of the fourteen specimens Lake brought out were in stasis, and it was they who devastated the camp. Perhaps not maliciously, more from fear, even curiosity. And there was more.” He shuddered. “These beings originally had total mastery over organic life, and in their earlier times had developed a slave species, something hinted at in certain ancient texts and named shoggoths. It was said they could perform any task by taking on any form. They constituted the ultimate archetype in their infinite plasticity.”

Tremont and I locked eyes and we stared at the monitor, where those unspecified cells had taken on a very definite course of development and entered their sixth generation already— every cell at the initiation of division had now given rise to 64 daughter cells. Doubling at each iteration was an exponential curve.

Moriarty drove himself to continue. “They built a whole world for their masters, but developed independent sentience, realized they were slaves, and tore it down once more. It would seem one or more were very much alive, with access to a subterranean sea which sustained them.”

“Sea?” I murmured. “Aquifer? If one connected to the other beneath the mountains.” For a moment I thought Tremont would scoff and throw the old man out of the lab, but the behavior of the tissue matched what we had been told in the most horrifying way. Though scientifically lost, he nodded. “A creature whose tissue is permanently capable of re-expressing in any new form required.” He shook his head, his composure nigh failing. “All it takes is energy— sunlight to thaw and reanimate eon-old corpses?”

“So laser excitation should do something similar on the cellular scale,” I whispered. Our eyes met and I felt my legs go weak for a moment. “What about ultraviolet…?” We looked at the connecting door to the main lab and, by inference, the biohazard room beyond, where, for the last seven hours or so, the original specimen had stood bathed in energy.

Moriarty was forgotten as we scrambled for the observation bay, flicked on the lights, and the sight that greeted us was enough to strike us dead on the spot had we been of lesser mettle. Beyond the transparent aluminum partitions, the containment vessel had long since burst open, and the lab was a chaos of smashed equipment, cold cabinets torn open and their contents, a hundred different substances, splashed near and far, by the insensate gropings of the thing which occupied much of the room. The original fist-sized lump of repulsive tissue had soaked up the stream of energy from the lamps, used it to trigger reorganization, and likely absorbed the carbon from the Parafilm to launch growth. The vessels lay shattered, and amongst them wallowed such an abomination as words can not describe.

Tissues were semi-translucent, pinkish globules, splotched with black marl, chained together with sheets of membrane from which issued tentacular members which writhed and coiled, searching near and far, and cramming the last scraps of any substance it could find among the ransacked supplies into any of the multiple mouths which gaped obscenely, like fang-spiked tropic fruits turned inside out. Most appalling of all were the eyes, however, like malevolent black jewels, scattered across the mass with as little order or sense as the mouths, yet like human eyes, windows to a soul—expressing only hunger.

They swivelled as one as the creature caught our motion. We jumped back involuntarily as it cannoned across the lab, smashing chairs as it came, and fetched up against the transparency with a dull shuddering and thudding as its arms beat and flailed for purchase. We felt physically sick as we looked upon a shoggoth, a million years out of its time, a world from its place, randomly triggered to being without cause or purpose, and now insensate with the only drive it knew—to eat. Eat us.

The CCTV in the lab would have been recording this degenerate spectacle from the beginning, and as the creature’s fury doubled in its assault upon the windows, Tremont took responsibility, whirled to a covered panel and tore it open. He swiped his staff ID, entered a PIN code, and warning lights came on. He closed a lever switch and steel shields lowered on the inner side to conceal the revolting thing, then he hammered a broad red contact with the heel of his hand and we felt a shock through the walls as the ultimate emergency precaution was enacted. Hydro-methane was injected into the chamber as the air conditioning ducts sealed, and a moment later the explosive mix was sparked in a high-temperature fireball. We felt heat through the partitions and tried not to think of what lay beyond as the lab was sterilized— nothing known could survive that—but of course, this was not known.

Sick at heart, we turned to find the old librarian in his wheelchair at the door, gray-faced but nodding with a tight, determined assent. We had done the only thing possible. The Security men were hammering at the outer door and I called them in as Tremont returned to the sequencing lab, and we stared at the mounted samples, even then dividing, though not yet visible to the naked eye. I was unsure what to say or do as he prepared a liquid nitrogen cryocontainer for them. He was enough of a researcher to know there may never be another chance to—more cautiously—explore the genome of what may be the progenitor of all higher life on Earth.

I said nothing but turned away, faint and clutching at a chair back for support, and the ancient librarian saw the dread in my eyes. Perhaps he did not fully understand what it meant, but the horror was unambiguous.

Truly this was a place of shadows and my father was right; once touched by the ghosts of these Arkham hills, one’s soul was forever bereft of the bliss of naivete.

Host Commentary

PseudoPod Episode 899

December 31st 2023

Arcanum Miskatonica by Mike ADAMSON

Narrated by Josh Roseman

Audio Production by Chelsea Davis

Hosted by Alasdair Stuart

Welcome to PseudoPod, the weekly horror podcast. I’m Alasdair, your host and this week’s story comes to us from Mike Adamson, wrapped in a beautiful moment of numerical and calendrical serendipity. Episode 899 falling on the last day of the year, means we start a new year with two clean, round zeroes and a 9. That’s very cool.

As is this story which is part of, and concludes I suspect, our 2023 Anthology & Collection Showcase. It was originally published in Lovecraftiana Vol.3, No.1, April 2018 and reprinted in the 2023 anthology The Nameless Songs of Zadok Allen & Other Things that Should Not Be edited by Jessica Augustsson

The Nameless Songs of Zadok Allen & Other Things that Should Not Be is JayHenge’s 20th speculative fiction anthology, and editor Jessica Augustsson and her team had so much fun putting it together. She says, “ There were so many brilliant submissions, and we were lucky enough to be able to get a foreword by Elena Tchougounova-Paulsen, the editor of Lovecraftian Proceedings, a journal on academic Lovecraftiana. Mike Adamson’s work can be found in several other JayHenge anthologies, along with so many truly wonderful writers. We’re very excited to get even more eyes (and ears) on their work!”

Mike Adamson holds a Doctoral degree from Flinders University of South Australia. After early aspirations in art and writing, Mike secured qualifications in both marine biology and archaeology. Mike has been a university educator since 2006, has worked in the replication of convincing ancient fossils, is a passionate photographer, master-level hobbyist, and journalist for international magazines. Short fiction sales include to Metastellar, Strand Magazine, Little Blue Marble, Abyss and Apex, Daily Science Fiction, Compelling Science Fiction and Nature Futures. Mike has placed on over two hundred occasions to date, totaling over a million words. Mike has completed his first Sherlock Holmes novel with Belanger Books and has appeared in translation in European magazines. You can catch up with his journey at his blog ‘The View From the Keyboard,’ mike-adamson.blogspot.com

Your narrator for the week is Josh Roseman, Chelsea is running the audio magic and I’m your host so without further ado, for the last time in this 18,000 month long year, we have a story for you and we promise you the readings check out and it’s true.

Oh I LIKE this. Long-term listeners will know that Lovecraftian stuff’s tendency to play the same, dreadful ululating, non-Euclidean hits is a hard sell for me but Lovecraftian stuff done like this? This I am here for All Day.

What sings for me here, in those terrible notes, is Mike’s clear eye for human nature. Our hero knows that Miskatonic is off. Everyone knows Miksatonic is OFF. It’s a place where you go to make your reputation or die or, sometimes, both and the story does a neat job of walking right up to the very real reasons certain Universities have a bad reputation without using that for a cheap pop. Instead, it’s presented the same way banal evil is. It’s just the culture. It’s just how we do things. Tradition, a suit of armour for the establishment and a cloak to muffle the voices of the people they exploit and rely upon.

Mike does a superb joy of showing our hero skate across that thin ice, pulled by the subtle dark gravity of the Old Sciences. I love the description of the labs, ossified in different time periods. I love the sense that the sample was left there at the end of a story we didn’t quite see. A predecessor, smart enough to not touch it, tainted enough to not destroy it. A booby trap, left armed by someone who escaped but who was too scared to diffuse it,

I love Moriarty too, so comfortable in his role as Scary Librarian Who Knows Things and so abjectly terrified when something is actually done with the knowledge. The hubris and pride of academic gatekeeping burned away by the fact something large and hungry that only knows how to get larger and hungrier is awake and NEXT. DOOR.

That’s where the horror of the story truly lies for me. Not in the shadows, not in the faded photos of a doomed expedition but under the halogen lights of a lab containing an impossibility.

For.

Now.

It’s why Moriarty loses it, the thin veneer of academic arrogance replaced by human terror. Miskatonic is a campus full of unexploded bombs and this one, red in tooth and so many claws, is in the process of exploding. But the horror also sits in the fact this sort of thing happens so often the atmosphere on campus is…off. This is Miskatonic. The apocalypse is Wednesday and crimes against nature are Monday thru Friday inclusive.

But the element of this story that really surprises me is the fact there’s a hero. Cometh the hour cometh the Dave Tremont. The stoical pragmatism of our two fisted science buddy saves the day here and while it may be temporary it’s certainly good enough for now. But even then there’s a hint of justification. Miskatonic continues to exist because of people like Dave. It continues to almost collapse because of people like Moriarty. The hero isn’t quite either.

What a story! And brilliantly read and produced, thank you both.

We rely on you to pay our authors, our narrators and our crew, and to cover our costs. We’re entirely donation funded and this year that’s changed in some very exciting ways with becoming a registered US nonprofit. We’ve launched our first end of year campaign to raise awareness about all the new ways you can help us out including workplace giving and employer matching, donor advised funds, and lots more. And if you pay taxes in the US, you might be able to claim a deduction. Check out the short metacast on escapeartists.net for more ideas, and how to get in touch if you think of something else that’s more meaningful to you.

One-time donations are fantastic and gratefully received, but what really makes a difference is subscribing. Subscriptions get us stability and a reliable income we use to bring free and accessible audio fiction to the world. You can subscribe for a monthly or annual donation through PayPal or Patreon. And if you sign up for an annual subscription on Patreon, there’s a discount available from now until the end of the year.

Not only do you help us out immensely when you subscribe or donate but you get access to a raft of bonus audio. You help us, we help you and everything becomes just a little easier. Even if you can’t donate financially, please consider spreading the word about us. If you liked an episode then please consider sharing it on social media, or blogging about us or leaving a review it really does all help and thank you once again

Episode 899 hitting on December 31st. The end of a hundred, the end of a year that has at times felt a hundred years long for me and a blank slate just around the corner, Massive thanks as ever to our amazing teams, everyone at Cast of Wonders, PodCastle, CatsCast and Escape Pod. The Tentacles, what a team you are. Kat, Alex, Shawn, Scott, Chelsea, every associate, every wrangler, every social media ninja. Thank you all. Thanks too to everyone in financial, everyone on the board, the amazing Marguerite who I love completely and to you. The reason we’re here and the reason we continue to be here. Thank you.

And speaking of continuing, PseudoPod kicks off it’s 900s and it’s 2024 with The Vengeance of Nitocris by Tennessee Williams. Yep THAT ONE. It’s a public domain story produced by Chelsea and hosted by Lisa Yazsek. It’ll be with you next week. Then as now it will be a production of the Escape Artists Foundation and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. And PseudoPod wants you to remember It is absolutely necessary, for the peace and safety of mankind, that some of earth’s dark, dead corners and unplumbed depths be let alone; lest sleeping abnormalities wake to resurgent life, and blasphemously surviving nightmares squirm and splash out of their black lairs to newer and wider conquests.

Happy new year everyone! See you next time.

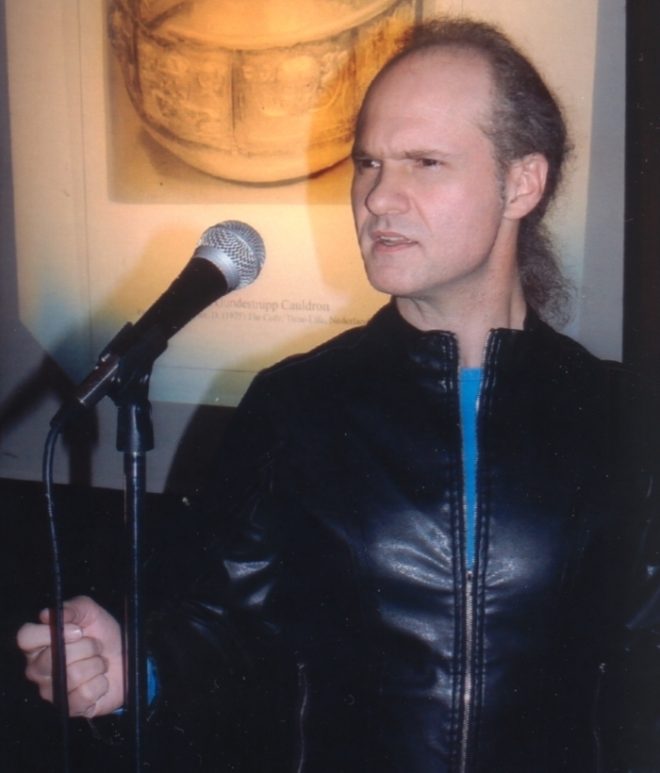

About the Author

Mike Adamson

Mike Adamson holds a Doctoral degree from Flinders University of South Australia. After early aspirations in art and writing, Mike secured qualifications in both marine biology and archaeology. Mike has been a university educator since 2006, has worked in the replication of convincing ancient fossils, is a passionate photographer, master-level hobbyist, and journalist for international magazines. Short fiction sales include to Metastellar, Strand Magazine, Little Blue Marble, Abyss and Apex, Daily Science Fiction, Compelling Science Fiction and Nature Futures. Mike has placed on over two hundred occasions to date, totaling over a million words. Mike has completed his first Sherlock Holmes novel with Belanger Books, and has appeared in translation in European magazines. You can catch up with his journey at his blog ‘The View From the Keyboard,’

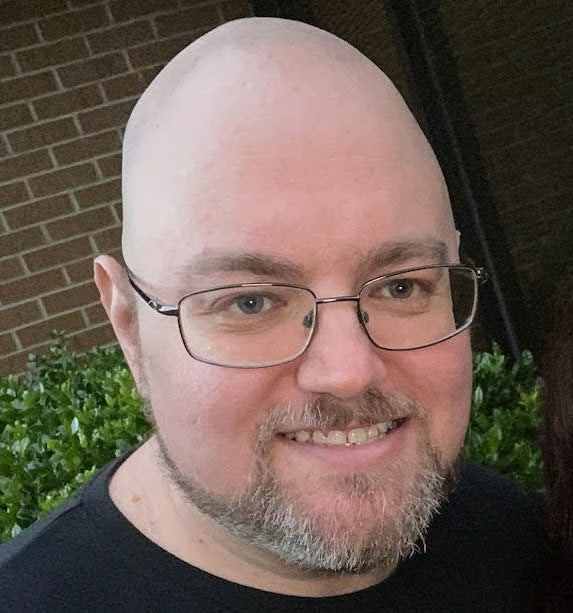

About the Narrator

Josh Roseman

Josh Roseman (not the trombonist; the other one) lives in Georgia and writes science fiction, fantasy, horror, and romance. When not writing, he mostly complains about not writing. Follow him on Twitter, Threads, Instagram, or Bluesky @Listener42, where he often posts pictures of his dog.