PseudoPod 996: The Suitable Surroundings and The Resurrection of Chilton Hills

Show Notes

- J. F. Martel on the idea of synchronicities ? https://www.weirdstudies.com/2

- Carnival of Souls trailer ? https://www.criterion.com/films/607-carnival-of-souls

- Josh’s academic musings on the idea of the Spooky ? https://www.academia.edu/113602949/Dancing_in_the_Ruins_Toward_an_Affect_Narratology_of_the_Spooky

- The essay Josh refers to in the outro ? Bahr, Howard W. “Ambrose Bierce and Realism.” Critical Essays on Ambrose Bierce, edited by Cathy N. Davidson. G. K. Hall & Co., 1982, pp. 150 – 168.

- The disappearance of Ambrose Bierce ? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ambrose_Bierce#Disappearance

Ben Phillips’s music ? Painful Reminder

The Suitable Surroundings

By Ambrose Bierce

THE NIGHT

ONE midsummer night a farmer’s boy living about ten miles from the city of Cincinnati was following a bridle path through a dense and dark forest. He had lost himself while searching for some missing cows, and near midnight was a long way from home, in a part of the country with which he was unfamiliar. But he was a stout-hearted lad, and knowing his general direction from his home, he plunged into the forest without hesitation, guided by the stars. Coming into the bridle path, and observing that it ran in the right direction, he followed it.

The night was clear, but in the woods it was exceedingly dark. It was more by the sense of touch than by that of sight that the lad kept the path. He could not, indeed, very easily go astray; the undergrowth on both sides was so thick as to be almost impenetrable. He had gone into the forest a mile or more when he was surprised to see a feeble gleam of light shining through the foliage skirting the path on his left. The sight of it startled him and set his heart beating audibly.

“The old Breede house is somewhere about here,” he said to himself. “This must be the other end of the path which we reach it by from our side. Ugh! what should a light be doing there?”

Nevertheless, he pushed on. A moment later he had emerged from the forest into a small, open space, mostly upgrown to brambles. There were remnants of a rotting fence. A few yards from the trail, in the middle of the “clearing,” was the house from which the light came, through an unglazed window. The window had once contained glass, but that and its supporting frame had long ago yielded to missiles flung by hands of venture- some boys to attest alike their courage and their hostility to the supernatural; for the Breede house bore the evil reputation of being haunted. Possibly it was not, but even the hardiest sceptic could not deny that it was deserted—which in rural regions is much the same thing.

Looking at the mysterious dim light shining from the ruined window the boy remembered with apprehension that his own hand had assisted at the destruction. His penitence was of course poignant in proportion to its tardiness and inefficacy. He half expected to be set upon by all the unworldly and bodiless malevolences whom he had outraged by assisting to break alike their windows and their peace. Yet this stubborn lad, shaking in every limb, would not retreat. The blood in his veins was strong and rich with the iron of the frontiersman. He was but two removes from the generation that had subdued the Indian. He started to pass the house.

As he was going by he looked in at the blank window space and saw a strange and terrifying sight,—the figure of a man seated in the centre of the room, at a table upon which lay some loose sheets of paper. The elbows rested on the table, the hands supporting the head, which was uncovered. On each side the fingers were pushed into the hair. The face showed dead-yellow in the light of a single candle a little to one side. The flame illuminated that side of the face, the other was in deep shadow. The man’s eyes were fixed upon the blank window space with a stare in which an older and cooler observer might have discerned something of apprehension, but which seemed to the lad altogether soulless. He believed the man to be dead.

The situation was horrible, but not with out its fascination. The boy stopped to note it all. He was weak, faint and trembling; he could feel the blood forsaking his face. Nevertheless, he set his teeth and resolutely advanced to the house. He had no conscious intention—it was the mere courage of terror. He thrust his white face forward into the illuminated opening. At that instant a strange, harsh cry, a shriek, broke upon the silence of the night the note of a screech-owl. The man sprang to his feet, overturning the table and extinguishing the candle. The boy took to his heels.

THE DAY BEFORE

“Good-morning, Colston. I am in luck, it seems. You have often said that my commendation of your literary work was mere civility, and here you find me absorbed—actually merged—in your latest story in the Messenger. Nothing less shocking than your touch upon my shoulder would have roused me to consciousness.”

“The proof is stronger than you seem to know,” replied the man addressed: “so keen is your eagerness to read my story that you are willing to renounce selfish considerations and forego all the pleasure that you could get from it.”

“I don’t understand you,” said the other, folding the newspaper that he held and putting it into his pocket. “You writers are a queer lot, anyhow. Come, tell me what I have done or omitted in this matter. In what way does the pleasure that I get, or might get, from your work depend on me?”

“In many ways. Let me ask you how you would enjoy your breakfast if you took it in this street car. Suppose the phonograph so perfected as to be able to give you an entire opera,—singing, orchestration, and all; do you think you would get much pleasure out of it if you turned it on at your office during business hours? Do you really care for a serenade by Schubert when you hear it fiddled by an untimely Italian on a morning ferryboat? Are you always cocked and primed for enjoyment? Do you keep every mood on tap, ready to any demand? Let me remind you, sir, that the story which you have done me the honor to begin as a means of becoming oblivious to the discomfort of this car is a ghost story!”

“Well?”

“Well! Has the reader no duties corresponding to his privileges? You have paid five cents for that newspaper. It is yours. You have the right to read it when and where you will. Much of what is in it is neither helped nor harmed by time and place and mood; some of it actually requires to be read at once—while it is fizzing. But my story is not of that character. It is not ‘the very latest advices’ from Ghostland. You are not expected to keep yourself au courant with what is going on in the realm of spooks. The stuff will keep until you have leisure to put yourself into the frame of mind appropriate to the sentiment of the piece—which I respectfully submit that you cannot do in a street car, even if you are the only passenger. The solitude is not of the right sort. An author has rights which the reader is bound to respect.”

“For specific example?”

“The right to the reader’s undivided attention. To deny him this is immoral. To make him share your attention with the rattle of a street car, the moving panorama of the crowds on the sidewalks, and the buildings beyond—with any of the thousands of distractions which make our customary environment—is to treat him with gross injustice. By God, it is infamous!”

The speaker had risen to his feet and was steadying himself by one of the straps hanging from the roof of the car. The other man looked up at him in sudden astonishment, wondering how so trivial a grievance could seem to justify so strong language. He saw that his friend’s face was uncommonly pale and that his eyes glowed like living coals.

“You know what I mean,” continued the writer, impetuously crowding his words—”you know what I mean, Marsh. My stuff in this morning’s Messenger is plainly sub-headed ‘A Ghost Story.’ That is ample notice to all. Every honorable reader will understand it as prescribing by implication the conditions under which the work is to be read.”

The man addressed as Marsh winced a trifle, then asked with a smile: “What conditions? You know that I am only a plain business man who cannot be supposed to understand such things. How, when, where should I read your ghost story?”

“In solitude—at night—by the light of a candle. There are certain emotions which a writer can easily enough excite—such as compassion or merriment. I can move you to tears or laughter under almost any circumstances. But for my ghost story to be effective you must be made to feel fear—at least a strong sense of the supernatural—and that is a difficult matter. I have a right to expect that if you read me at all you will give me a chance; that you will make yourself accessible to the emotion that I try to inspire.”

The car had now arrived at its terminus and stopped. The trip just completed was its first for the day and the conversation of the two early passengers had not been interrupted. The streets were yet silent and desolate; the house tops were just touched by the rising sun. As they stepped from the car and walked away together Marsh narrowly eyed his companion, who was reported, like most men of uncommon literary ability, to be addicted to various destructive vices. That is the revenge which dull minds take upon bright ones in resentment of their superiority. Mr. Colston was known as a man of genius. There are honest souls who believe that genius is a mode of excess. It was known that Colston did not drink liquor, but many said that he ate opium. Something in his appearance that morning—a certain wildness of the eyes, an unusual pallor, a thickness and rapidity of speech—were taken by Mr. Marsh to confirm the report. Nevertheless, he had not the self-denial to abandon a subject which he found interesting, however it might excite his friend.

“Do you mean to say,” he began, “that if I take the trouble to observe your directions—place myself in the conditions that you demand: solitude, night and a tallow candle—you can with your ghostly work give me an uncomfortable sense of the supernatural, as you call it? Can you accelerate my pulse, make me start at sudden noises, send a nervous chill along my spine and cause my hair to rise?”

Colston turned suddenly and looked him squarely in the eyes as they walked. “You would not dare—you have not the courage,” he said. He emphasized the words with a contemptuous gesture. “You are brave enough to read me in a street car, but—in a deserted house—alone—in the forest—at night! Bah! I have a manuscript in my pocket that would kill you.”

Marsh was angry. He knew himself courageous, and the words stung him. “If you know such a place,” he said, “take me there to-night and leave me your story and a candle. Call for me when I’ve had time

enough to read it and I’ll tell you the entire plot and—kick you out of the place.”

That is how it occurred that the farmer’s boy, looking in at an unglazed window of the Breede house, saw a man sitting in the light of a candle.

THE DAY AFTER

Late in the afternoon of the next day three men and a boy approached the Breede house from that point of the compass toward which the boy had fled the preceding night. The men were in high spirits; they talked very loudly and laughed. They made facetious and good-humored ironical remarks to the boy about his adventure, which evidently they did not believe in. The boy accepted their raillery with seriousness, making no reply. He had a sense of the fitness of things and knew that one who professes to have seen a dead man rise from his seat and blow out a candle is not a credible witness.

Arriving at the house and finding the door unlocked, the party of investigators entered without ceremony. Leading out of the passage into which this door opened was another on the right and one on the left. They entered the room on the left—the one which had the blank front window. Here was the dead body of a man.

It lay partly on one side, with the forearm beneath it, the cheek on the floor. The eyes were wide open; the stare was not an agreeable thing to encounter. The lower jaw had fallen; a little pool of saliva had collected beneath the mouth. An overthrown table, a partly burned candle, a chair and some paper with writing on it were all else that the room contained. The men looked at the body, touching the face in turn. The boy gravely stood at the head, assuming a look of ownership. It was the proudest moment of his life. One of the men said to him, “You’re a good ‘un”—a remark which was received by the two others with nods of acquiescence. It was Scepticism apologizing to Truth. Then one of the men took from the floor the sheet of manuscript and stepped to the window, for already the evening shadows were glooming the forest. The song of the whip-poor-will was heard in the distance and a monstrous beetle sped by the window on roaring wings ,and thundered away out of hearing. The man read:

THE MANUSCRIPT

“Before committing the act which, rightly or wrongly, I have resolved on and appearing before my Maker for judgment, I, James R. Colston, deem it my duty as a journalist to make a statement to the public. My name is, I believe, tolerably well known to the people as a writer of tragic tales, but the somberest imagination never conceived anything so tragic as my own life and history. Not in incident: my life has been destitute of adventure and action. But my mental career has been lurid with experiences such as kill and damn. I shall not recount them here—some of them are written and ready for publication elsewhere. The object of these lines is to explain to whomsoever may be interested that my death is voluntary—my own act. I shall die at twelve o’clock on the night of the 15th of July—a significant anniversary to me, for it was on that day, and at that hour, that my friend in time and eternity, Charles Breede, performed his vow to me by the same act which his fidelity to our pledge now entails upon me. He took his life in his little house in the Copeton woods. There was the customary verdict of ‘temporary insanity.’ Had I testified at that inquest—had I told all I knew, they would have called me mad!”

Here followed an evidently long passage which the man reading read to himself only. The rest he read aloud.

“I have still a week of life in which to arrange my worldly affairs and prepare for the great change. It is enough, for I have but few affairs and it is now four years since death became an imperative obligation.

“I shall bear this writing on my body; the finder will please hand it to the coroner.

“James R. Colston.

“P. S.—Willard Marsh, on this the fatal fifteenth day of July I hand you this manuscript, to be opened and read under the conditions agreed upon, and at the place which I designated. I forego my intention to keep it on my body to explain the manner of my death, which is not important. It will serve to explain the manner of yours. I am to call for you during the night to receive assurance that you have read the manuscript. You know me well enough to expect me. But, my friend, it will be after twelve o’clock. May God have mercy on our souls!

“J. R. C.”

Before the man who was reading this manuscript had finished, the candle had been picked up and lighted. When the reader had done, he quietly thrust the paper against the flame and despite the protestations of the others held it until it was burnt to ashes. The man who did this, and who afterward placidly endured a severe reprimand from the coroner, was a son-in-law of the late Charles Breede. At the inquest nothing could elicit an intelligent account of what the paper had contained.

FROM “THE TIMES”

“Yesterday the Commissioners of Lunacy committed to the asylum Mr. James R. Colston, a writer of some local reputation, connected with the Messenger. It will be remembered that on the evening of the I5th inst. Mr. Colston was given into custody by one of his fellow-lodgers in the Baine House, who had observed him acting very suspiciously, baring his throat and whetting a razor—occasionally trying its edge by actually cutting through the skin of his arm, etc. On being handed over to the police, the unfortunate man made a desperate resistance, and has ever since been so violent that it has been necessary to keep him in a strait-jacket. Most of our esteemed contemporary’s other writers are still at large.”

The Resurrection Of Chilton Hills

by Philip Curtiss

I had a strange experience, not long ago. I had an invitation to spend a weekend in Chilton Hills, and it is quite impossible to describe the sensation it gave me. It was much as if I had been asked for a weekend in Thebes.

Twenty-five years ago, of course, Chilton Hills was probably the smartest resort in America, and a visit there was like a novel by Ouida at the height of her fame. The place had, I believe, the first eighteen-hole golf links in this country, and at one time two others were under construction. It had the best polo field away from Long Island, and in the autumn there was fox-hunting three times a week.

The North-eastern tennis championship was played there every summer, and a famous man-about-town once remarked that it was the only place outside of New York where one could always be sure of good bridge. During a visit that I made one college vacation there was a dance every night at the country club or one of the cottages, and that year appeared the daring innovation of dancing in the afternoon.

Only vaguely, out of the kaleidoscopic haze of that momentous fortnight, do I remember a vast jumble of lesser events such as paperchases, regattas on the lake, and morning concerts by a string quartet, although I do recall that when we younger guests were starting off to play golf or ride, the older members of the household would usually be going to a lecture on the art of George Sand or an exhibition of Indian baskets.

Then something happened, and little by little Chilton Hills disappeared from the social map. Indeed, on my second visit, I wondered whether it had not also disappeared from the topographical map, for hardly had my car crossed the boundaries of the village when I began to feel that I was in a city of the dead.

On a hill near the center of the town was a gaunt stone chimney with a few charred beams to show where once had stood the finest country club in the United States. Beyond it loomed the empty shell of the famous Chilton Arms, a great summer hotel, with a rusted chain stretched across its gateway and its acres of windows now boarded up. At a turn in the road was a simple meadow, knee-deep in daisies and buttercups, with only a few rotted lengths of whitewashed fence to remind the traveler that once it had been a polo field.

Only a few private cottages, set back in their lawns and trees, seemed to be well kept and prosperous. Among them, happily, was the familiar place of my former host, Luke Munday; but if the public life of Chilton Hills had entirely disappeared, so, correspondingly, had the private life slowed down from eight or ten thousand revolutions a minute to two or three languid turns a year.

On my previous visit, as I could well remember, it had been several hours after my arrival before I had even time to unpack my bag, but now, as soon as the first formalities were over, Luke turned to me with an apologetic smile.

“Bob,” he confessed, “to be frank, I have the habit of taking a nap every afternoon. Do you mind being left alone?”

To tell the truth, it was so many years since I had been left alone, except in the subway, that I didn’t know whether I minded or not. For two or three minutes I wandered around, feeling quite lost and ill at ease, then suddenly I saw a steamer chair ranged invitingly on a cool, shaded terrace. As I stretched out luxuriously, my eye was caught by a book that someone had left on the bricks at my feet and, the next thing I knew, I was being called for dinner.

And that was exactly the pace at which we passed the whole weekend. In the evening, Helen Munday played the piano in rambling fashion while Luke and I loafed at full length and smoked our cigars. Nobody came in, nobody went out, and I do not recall that the telephone rang during my entire visit.

On Saturday we strolled down to a pond in the woods, undressed in an old barn, and went in for a swim. On Sunday night we found ourselves again on the terrace with crickets chirping in a neighboring hayfield and, over our heads, a blanket of stars. It was funny but, actually, I seemed to have forgotten that there still were stars and crickets. I had an unconscious feeling that when the movies and motorcars had come in they had gone out.

It was beautiful, it was incredibly beautiful, but it was all so different from the old Chilton Hills that I could not lose the sensation that there was some mystery about it, something that should be explained. At the same time I could see that it might easily be a tender subject, and it was only there under the stars that I found a way to make guarded inquiries.

“Luke,” I asked, “have you been here ever since the old days?”

“Oh, no,” answered Luke, easily, “there were eight or ten summers that the house was closed. We only came back when we heard that the country club had burned down.”

“You mean,” I asked, vaguely, “that you meant to rebuild it?”

“Decidedly not,” replied Luke. “We came back only when we felt sure that it never would be rebuilt.”

His words did not seem exactly to be making sense, and for a moment longer I floundered around.

“But what,” I asked, “has become of the other people that used to be here: the Haddons —wasn’t that their name? — and that polo man with the awfully pretty wife — and that brisk, breezy chap who used to be something important in steel?”

“Oh, they’re still here,” answered Luke. “You’d probably see them if you stayed around long enough. Most of them went away, as I did, for a while, but in the end they all came back. Of course,” he added, “for a man in my circumstances it is the wildest extravagance to be living here now.”

If his previous words had been somewhat mysterious, these last were a cryptogram.

Luke explained.

“Oh, it isn’t the cost of living. That’s simple enough. It’s the value of the land. Land today in Chilton Hills is worth five times as much as it was in the old days. If I would consent to sell this place I could get enough to live in luxury for the rest of my life.”

“But why?” I demanded. “What makes it so valuable?”

“The fact,” replied Luke, “that Chilton Hills today is a spot absolutely unique.”

Then, apparently seeing that he must tell once again what was to him a very old story, Luke leaned back and began.

“You remember, of course, what Chilton Hills was like in the old days?”

“Yes, I remember very clearly. It was—”

“It was a nightmare,” broke in Helen, sharply.

Luke laughed. “I’m afraid it was before we got through. You know, most Americans are still pure savages when it comes to pleasure. A savage believes that if one quinine pill will do him good, twenty quinine pills will do him twenty times as much good. And that used to be exactly the state of mind here in Chilton Hills.

“Because we had fun with one golf links, we thought we would have twice as much fun with two. Because we got a thrill from a little scrub polo team that beat everything in the county, we thought we would have a bigger thrill if we got better players and beat everything in the world. Because we liked to dance once a week, we tried to be six times as happy by dancing every night.

“The result was that in the end we were so highly organized and equipped for pleasure that we didn’t have any more fun. We were so busy organizing tournaments and taking tickets for polo games and running to railways to meet musicians for our concerts that we no longer had any time to play in the tournaments or watch the polo, or listen to the music.

“One summer I was treasurer or secretary of eight different drives or committees or organizations, I was selling a million dollars’ worth of bonds for the new country club and at the same time I was trying to run a business of my own in New York. Everybody else was just as busy and, apart from this, we had our private entertaining. That same summer we went to forty-three formal dinners and gave eleven in return. When my vacation was over I was flat on my back.”

“And then what happened?”

“Well, I for one,” replied Luke, “simply woke up. Helen and I faced the situation and asked each other, ‘What for?’ The next summer we went to a little resort in Germany where we didn’t know a soul and couldn’t even speak the language and had a perfectly glorious time. It was such a success that for nine years we went abroad every summer, always seeking a place where we were absolutely unknown.

“One by one all the other old families did much the same thing. The sports and dances dropped off for lack of support, then the country club burned down, and in five years the town was flat.

“But after all,” continued Luke, “home is home, and in the end we had a bright idea. When Chilton Hills was no longer smart or popular we quietly slipped back here and had the most peaceful, unbroken summer we had ever known. But the trouble was that most of the other old timers each had the same idea, and the first thing we knew the old state of affairs was threatening to start up again.

“You know, among any dozen given people, there is always some ass who is never happy unless he is organizing something, and very shortly someone decided to get up a bazaar for the benefit of the visiting nurse. A dozen of us who were still jumpy from the old days saw the danger and we offered to give a thousand dollars if they wouldn’t have the bazaar. From that simple beginning grew one of the most remarkable organizations in the world—The Red Ticket Club.”

“It sounds good,” I said. “What is it?”

“Every year,” replied Luke, “each householder in Chilton Hills pays a hundred dollars and is given a red ticket. This exempts him from subscribing to or attending any bazaar, masquerade, treasure hunt, musicale, ball, dance, hop, or any public event of any kind whatsoever and, if he is even asked to a private dinner and does not care to go, all he has to do is reply ‘Red Ticket’ and nothing more is said.

“Out of the funds thus collected are supported the church, the fire department, the library, the local Red Cross; and any surplus funds are given to foreign missions. In two years we had applications for membership from all over the United States, and you couldn’t get an inch of ground in Chilton Hills for love or money. As a matter of fact, we ourselves buy up any bits of property that come on the market, and to celebrate our tenth anniversary we bought the old Chilton Arms just for the fun of seeing it rot.”

“It sounds like a work of genius,” I suggested, “but what are you going to do when another, more foolish generation comes along?”

“Alas,” said Luke, “that is already one of our greatest worries, but the only thing we have devised so far is the Chilton Memorial. Near the center of the town did you notice something that looks like the ruins of the old country club?”

“But isn’t it the ruins of the old club?”

“Oh, goodness, no. The real chimney blew down two years after the fire and the charred beams all crumbled away, so we had a replica of the chimney made in solid concrete and false wreckage in rust-proof steel. Every Fourth of July all the children of the town are taken to look at them—not collectively, mind you, but when their parents feel good and ready. Simply and sadly they are told the story of the old Chilton Hills and then they are shown an inscription at the base of the chimney—a big rock on which is carved a modified version of Shakespeare’s epitaph:

“‘Good friends, for Heaven’s sake forebeare

To digg the dust encloased heare;

Bleste be the man that spares the stones

And curst be he that moves my bones.’”

Host Commentary

I spend a lot of time thinking about what Carl Jung called “synchronicities.” A synchronicity is essentially a meaningful coincidence: one thing occurs that seems to have bearing on another, even though there is no causal link between the two of them. It’s pure co-incidence. The concept of synchronicities gets a lot of attention in circles that study “the weird,” one of the best examples being the discussion of Twin Peaks: The Return in the second episode of the Weird Studies podcast. In that episode, J.F. Martel explains the idea with the following example:

Imagine you are walking through the forest and you encounter a tree that appears to have grown in the shape of your own initials. In the middle of these initials is a gleaming, red stone. By every appearance, the trees must have been set up in such a way as to ensure you would discover this stone. You can argue that it just happened that way, and means nothing, but you can’t argue that (in my case) there isn’t a J, and a B, and a T. The causal nexus of forces is separate from the effect, which—and this is why I like the way Martel explains it so much—cannot be reduced to the causes. In other words, we wouldn’t have to believe anything violating the known laws of causality had occurred in order to recognize that something very strange had happened, and that we were affected by it.

Hosting an episode for these two stories, at this particular time, generated a synchronicity for me. This is an audio podcast, so you don’t get the benefit of my yarn board but stay with me if you can. I promise it’s all connected.

In my academic work I talk about something I call “the Spooky.” I’ll say more about what I think that is in a minute, but the most relevant thing is that Ambrose Bierce could have saved me a lot of ink and heartache if I’d just turned in his story instead of spending two years writing an article. The bottom line is I think Colston was right—both about the author deserving the reader’s undivided attention, which sits uncomfortably with me given that I work for a podcast that people probably listen to while doing something else, even if they’re listening attentively—and about the more general point he makes. There are certain conditions under which a ghost story might succeed or fail that have less to do with the plot and more to do with the surrounding conditions. Some of those are internal to the story, and some of them aren’t. I love horror because it is rhetorical and affect driven. The author of a horror story is trying to produce a bodily and emotional effect in the reader to a greater extent than the authors of most other types of literature do. Alone, at night, by candlelight, in a potentially haunted house, is a pretty good way to make sure we’re “accessible to the emotion that [the author tries] to inspire.” I love it doubly in this story because the logic works to its deadly conclusion within the narrative, even while as a reader outside it I still have significant influence over whether it works externally on me.

If a properly prepared state of mind is important, then, as Bierce’s luck would have it, I was already musing on the Spooky when I read “The Suitable Surroundings” in preparation for this episode.

I’m teaching a class in the honors program at my university this semester, and so I was invited to host the annual start-of-term honors film screening. I was to choose any film I wanted, screen it for the honors students, and lead a discussion about it afterward. I picked Carnival of Souls. If you’ve seen it, try to remember along with me. If you haven’t, stop what you’re doing and either watch the trailer linked in the show notes or wait until dark before pressing play again; don’t do anything else but listen, and just try to imagine. In one of the earliest scenes in the film, the protagonist is driving late at night through the deserts of Utah, and in the distance, off one side of a road, is a dark and imposing hulk of what can only be described as Navy Pier ripped out of downtown Chicago and dumped in the middle of nowhere. It’s a sort of shadowy old-timey bathing pavilion, playing frightening tricks on the viewer with perspective and scale, barely visible as more than a silhouette in the glorious black-and-white of the film. It’s weird. It’s haunted me. It’s inspired me. (A more modern version of the same effect appears in the underrated 2016 film Friend Request when the repeated visual motif of a castle in the distance eventually turns into something far more strange and sinister.) When the Carnival of Souls protagonist asks someone what it was that was out there in the desert, she’s told it was this, it was that, but, and I quote, “that’s years ago, though. It just stands out there now.” The ruins become the beating heart of the story, and everything that happens seems somehow to have its beginning and end in their midst.

Carnival of Souls had its origin in the director, Herk Harvey’s own fascination with the real-life ruins of the Saltair Pavilion, which no longer exists, but might have been what Karl Edward Wagner had in mind when he wrote the prologue for the lead story in his 1983 collection In a Lonely Place. (We ran Wagner in episode 560, by the way. One of my favorite episodes.) Here’s what Wagner said in that prologue:

There is an atmosphere of inutterable loneliness that haunts any ruin—feeling particularly evident in those places once given over to the lighter emotions. Wander over the littered grounds of an abandoned amusement park and feel the overwhelming presence of desolation. Flimsy booths with awnings tattered in the wind, rotting heaps of sun-bleached papier-mâché. Crumbling timbers of a roller coaster thrust upward through the jungle of weeds and debris—like ribs of some titanic unburied skeleton. The wind blows colder here; the sun seems dimmer. Ghosts of laughter, lost strains of raucous music can almost be heard. Speak, and your voice sounds strangely loud—and yet curiously smothered.

Or tour a neglected formal garden, with its termite-riddled arbors and gazebo. The lily pond is drained, choked with weeds and refuse. Only a few flowers or shrubs poke miserably through the rank undergrowth. Dense clots of weeds and vines overrun the paths and statuary. Here and there a shrub or rambling rose has grown into a wild, misshapen tangle. The flowers offer anemic blooms, where no hand gathers, no eye admires. No birds sing in that uncanny hush.

Such places are lairs of inconsolable gloom. After the brighter spirits have departed, shadows of despair and oppression assume their place. The area has been drained of its ability to support any further light emotion, and now, like weeds on eroded soil, only the darker sentiments can take root and flourish. These places are best left to the loneliness of their grief…

The image of the ruined pavilion in Carnival of Souls, and Wagner’s description of something quite like them, were at the core of my thinking when I finally articulated my theory of “the Spooky” in an academic article a few years ago. What I realized is that in stories of the supernatural, the story only works if the supernatural events occur in prepared ground—much as Colston states in Bierce’s “Suitable Surroundings.” In Bierce’s case—and I’m going to be very real with you, I don’t quite understand what happens in this story, but I’m there for it—it seems that sufficiently suitable surroundings can make the important bit happen even if there is no ghost. Here’s the thing, though. (Get the yarn board back out.) By way of the Bierce connection, we can come back full circle to Herk Harvey’s Pavilion: the plot of Carnival of Souls shares its central plot element with Bierce’s story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” You can’t have Carnival of Souls without Bierce. And I probably wouldn’t have ever understood the Spooky without Carnival of Souls. So I needed Bierce, and apparently had him, long before I read the bit that would have saved me all that trouble.

One of the more interesting essays I’ve read about Ambrose Bierce argues that Bierce’s relationship to literary realism “has its origin in his artistic purpose of presenting man and human nature as they appear to him, to tell the truth about what he has observed” (Bahr 163). The essayist wasn’t talking about “The Suitable Surroundings” when he wrote this, but elsewhere he takes special notice of “the importance Bierce places upon the imaginative faculty” (153). It might be relevant that Bierce essentially walked into the desert one day and vanished. As I’m reading it from the current Wikipedia copy, “His last known communication with the world was a letter he wrote there to Blanche Partington, a close friend, dated December 26, 1913. After closing this letter by saying, ‘As to me, I leave here tomorrow for an unknown destination,’ he vanished without a trace, one of the most famous disappearances in American literary history.” If a man such as this gives us the sketch of man as he is, and tells us a true story about what he thinks is there…well, we promised you we had a story for you, didn’t we?

What about Curtiss? Well, he’s part of this too. My big breakthrough in trying to think through what the Spooky might be came when I realized that the fascination ruins hold is actually because Ruins are a specific form of the Spooky. Paradoxically, I argued, what if Ruins served not as a painful reminder of a lost or traumatic past, visible indexes to past pain or physical reminders of present absences, but instead as a future-oriented possibility of an affective otherwise to pain, born of an encounter in suitable surroundings where our ontological categories might be less rigid than usual. I have a doctorate in Spooky Literature—it’s hard to let that go when I’m moonlighting here, so forgive the jargon and urgent tone. But I hope what I’m saying makes sense. I’ll try to connect it, at least.

Here’s what all of that has to do with “The Resurrection of Chilton Hills.” One of the editorial comments when we were considering running this story was that it was, and I quote, “Not for us really, in obviously any way[—]outside of the manufacturing of a legend for the children.” We obviously chose to run it. I think that’s right. This isn’t a horror story but it might be a spooky story.

The residents of Chilton Hills rebuilt their ruin when it fell down and crumbled away. It isn’t actually the ruin of the country club, but rather “something that looks like the ruins of the old country club.” It’s a simulacrum of sorts, but it’s convincing enough that those who don’t know can’t seem to tell the difference. The legend they made up for the children all but ensures that the next generation won’t realize it either. To them it’s a real Ruin. Paradoxically, this decaying symbol of something the adults in Chilton Hills were running from was necessary for their happiness. So they rebuild it, use it, count on it to ensure their future. The visible marker of the past they want to escape isn’t forgotten, just Ruined. And that makes it Spooky. Full circle.

Alisdair likes to ask, where is the horror in this story? I like to ask, what in this story allows us to escape the tyranny of the everyday? Paradoxically, horror is one of the things that achieves, or at least enables, this. I think. But the point is that you should want this. If you don’t, then that means there’s no way out, not even in our weirdest fiction.

So, the synchronicity. These stories, which seem somehow intimately intertwined with my ideas and thinking, landed on my desk at the exact moment when the relevant ideas and images were top of mind. And later this week, I’m going to Navy Pier, which looks like Saltair, with my sister, who introduced me to Wagner’s opening vignette about ruins that I quoted earlier. Round it goes; one more time, I suppose.

So, what of it? These things are baked into this art form—they have to be, or my ideas wouldn’t have had merit. I was bound to find them pretty much any time I was thinking about those things while reading for Pseudopod. And who else but my sister would have introduced me to Wagner? And we live in Chicago, so why wouldn’t we go see Navy Pier when family from out of state comes and are excited to see the city? Still. All those things at once?

Is there any meaningful implication here? No, of course not. But that isn’t necessarily the same thing as saying it doesn’t mean anything. I don’t know what, exactly, but I hope it means that I’ve got a Spooky sense of living. I said that you should want this. And you can have it. What I’ll leave you with is this:

If Wagner was right—and he seems convincing—you can take the Spooky with you. Not for the sake of inventing false history with which to haunt the living, but for the sake of injecting into the everyday the possibility of an otherwise. Wander the grounds of an amusement park. Tour that Ruined formal garden. This is direct address: you will feel it if you let it pull you.

About the Authors

Philip Curtiss

Philip Everett Curtiss (1885 – 1964) was a politician, novelist, and newspaper reporter. He served in the Connecticut Legislature from 1941 to 1947 and was a trial justice in Norfolk for fifteen years beginning in 1940. His stories were published in various magazines, including Harper’s Magazine.

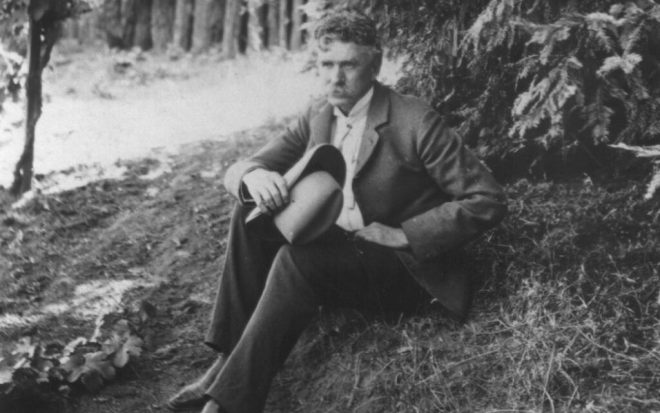

Ambrose Bierce

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce (June 24, 1842 – circa 1914) was an American editorialist, journalist, short story writer, fabulist, and satirist. He wrote the short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” and compiled a satirical lexicon, The Devil’s Dictionary. His vehemence as a critic, his motto “Nothing matters”, and the sardonic view of human nature that informed his work, all earned him the nickname “Bitter Bierce”.

Despite his reputation as a searing critic, Bierce was known to encourage younger writers, including the poets George Sterling and Herman George Scheffauer and the fiction writer W. C. Morrow. Bierce employed a distinctive style of writing, especially in his stories. His style often embraces an abrupt beginning, dark imagery, vague references to time, limited descriptions, impossible events, and the theme of war.

In 1913, Bierce traveled to Mexico to gain first-hand experience of the Mexican Revolution. He was rumored to be traveling with rebel troops, and was not seen again.

About the Narrators

Kaz

Kaz is actually three tentacles in a trench coat, able to mimic human speech through an obscure loophole in Eldritch Noise Ordinances. By day, Kaz pretends to be a member of the terrestrial band When Ukuleles Attack.

Ben Phillips

Ben Phillips is a programmer and musician living in New Orleans. He was a chief editor of Pseudopod from 2006-2010. He occasionally writes & records songs as Painful Reminder.