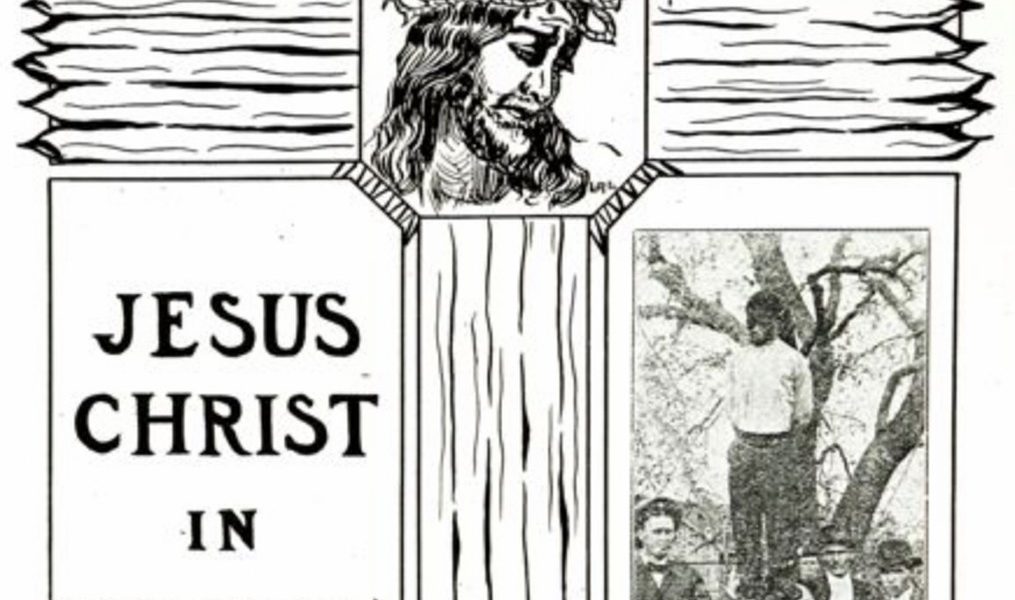

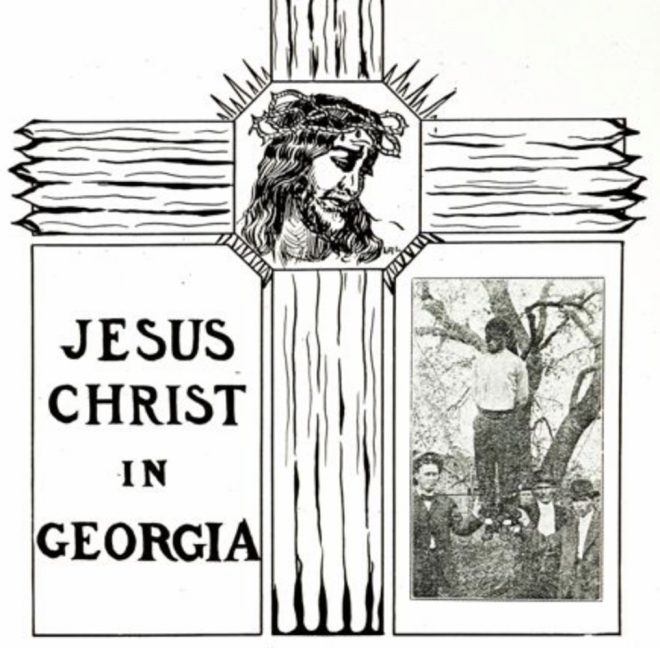

PseudoPod 980-B: Jesus Christ in Georgia

Show Notes

2010 interview with author Edward J. Blum about his 2008 book, W. E. B. DuBois, American Prophet: https://religiondispatches.org/iw-e-b-du-bois-american-propheti/

Jesus Christ in Georgia

By W.E.B. DuBois

The convict guard laughed. “I don’t know,” he said, “I hadn’t thought of that.” He hesitated and looked at the stranger curiously. In the solemn twilight he got an impression of unusual height and soft, dark eyes. “Curious sort of acquaintance for the colonel,” he thought; then he continued aloud: “But that nigger there is bad, a born thief, and ought to be sent up for life; got ten years last time——”

Here the voice of the promoter, talking within, broke in; he was bending over his figures, sitting by the colonel. He was slight, with a sharp nose.

“The convicts,” he said, “would cost us $96 a year and board. Well, we can squeeze this so that it won’t be over $125 apiece. Now if these fellows are driven, they can build this line within twelve months. It will be running by next April. Freights will fall fifty per cent. Why, man, you’ll be a millionaire in less than ten years.”

The colonel started. He was a thick, short man, with a clean-shaven face and a certain air of breeding about the lines of his countenance; the word millionaire sounded well to his ears. He thought—he thought a great deal; he almost heard the puff of the fearfully costly automobile that was coming up the road, and he said:

“I suppose we might as well hire them.”

“Of course,” answered the promoter.

The voice of the tall stranger in the corner broke in here:

“It will be a good thing for them?” he said, half in question.

The colonel moved. “The guard makes strange friends,” he thought to himself. “What’s this man doing here, anyway?” He looked at him, or rather looked at his eyes, and then somehow he felt a warming toward him. He said:

“Well, at least, it can’t harm them; they’re beyond that.”

“It will do them good, then,” said the stranger again. The promoter shrugged his shoulders. “It will do us good,” he said.

But the colonel shook his head impatiently. He felt a desire to justify himself before those eyes, and he answered: “Yes, it will do them good; or at any rate it won’t make them any worse than they are.” Then he started to say something else, but here sure enough the sound of the automobile breathing at the gate stopped him and they all arose.

“It is settled, then,” said the promoter.

“Yes,” said the colonel, turning toward the stranger again. “Are you going into town?” he asked with the Southern courtesy of white men to white men in a country town. The stranger said he was. “Then come along in my machine. I want to talk with you about this.”

They went out to the car. The stranger as he went turned again to look back at the convict. He was a tall, powerfully built black fellow. His face was sullen, with a low forehead, thick, hanging lips, and bitter eyes. There was revolt written about his mouth despite the hang-dog expression. He stood bending over his pile of stones, pounding listlessly. Beside him stood a boy of twelve,—yellow, with a hunted, crafty look. The convict raised his eyes and they met the eyes of the stranger. The hammer fell from his hands.

The stranger turned slowly toward the automobile and the colonel introduced him. He had not exactly caught his name, but he mumbled something as he presented him to his wife and little girl, who were waiting.

As they whirled away the colonel started to talk, but the stranger had taken the little girl into his lap and together they conversed in low tones all the way home.

In some way, they did not exactly know how, they got the impression that the man was a teacher and, of course, he must be a foreigner. The long, cloak-like coat told this. They rode in the twilight through the lighted town and at last drew up before the colonel’s mansion, with its ghost-like pillars.

The lady in the back seat was thinking of the guests she had invited to dinner and was wondering if she ought not to ask this man to stay. He seemed cultured and she supposed he was some acquaintance of the colonel’s. It would be rather interesting to have him there, with the judge’s wife and daughter and the rector. She spoke almost before she thought:

“You will enter and rest awhile?”

The colonel and the little girl insisted. For a moment the stranger seemed about to refuse. He said he had some business for his father, about town. Then for the child’s sake he consented.

Up the steps they went and into the dark parlor where they sat and talked a long time. It was a curious conversation. Afterwards they did not remember exactly what was said and yet they all remembered a certain strange satisfaction in that long, low talk. Finally the nurse came for the reluctant child and the hostess bethought herself:

“We will have a cup of tea; you will be dry and tired.”

She rang and switched on a blaze of light. With one accord they all looked at the stranger, for they had hardly seen him well in the glooming twilight. The woman started in amazement and the colonel half rose in anger. Why, the man was a mulatto, surely; even if he did not own the Negro blood, their practised eyes knew it. He was tall and straight and the coat looked like a Jewish gabardine. His hair hung in close curls far down the sides of his face and his face was olive, even yellow.

A peremptory order rose to the colonel’s lips and froze there as he caught the stranger’s eyes. Those eyes,—where had he seen those eyes before? He remembered them long years ago. The soft, tear-filled eyes of a brown girl. He remembered many things, and his face grew drawn and white. Those eyes kept burning into him, even when they were turned half away toward the staircase, where the white figure of the child hovered with her nurse and waved good-night. The lady sank into her chair and thought: “What will the judge’s wife say? How did the colonel come to invite this man here? How shall we be rid of him?” She looked at the colonel in reproachful consternation.

Just then the door opened and the old butler came in. He was an ancient black man, with tufted white hair, and he held before him a large, silver tray filled with a china tea service. The stranger rose slowly and stretched forth his hands as if to bless the viands. The old man paused in bewilderment, tottered, and then with sudden gladness in his eyes dropped to his knees, and the tray crashed to the floor.

“My Lord and my God!” he whispered; but the woman screamed: “Mother’s china!”

The doorbell rang.

“Heavens! here is the dinner party!” exclaimed the lady. She turned toward the door, but there in the hall, clad in her night clothes, was the little girl. She had stolen down the stairs to see the stranger again, and the nurse above was calling in vain. The woman felt hysterical and scolded at the nurse, but the stranger had stretched out his arms and with a glad cry the child nestled in them. They caught some words about the “Kingdom of Heaven” as he slowly mounted the stairs with his little, white burden.

The mother was glad of anything to get rid of the interloper, even for a moment. The bell rang again and she hastened toward the door, which the loitering black maid was just opening. She did not notice the shadow of the stranger as he came slowly down the stairs and paused by the newel post, dark and silent.

The judge’s wife came in. She was an old woman, frilled and powdered into a semblance of youth, and gorgeously gowned. She came forward, smiling with extended hands, but when she was opposite the stranger, somewhere a chill seemed to strike her and she shuddered and cried:

“What a draft!” as she drew a silken shawl about her and shook hands cordially; she forgot to ask who the stranger was. The judge strode in unseeing, thinking of a puzzling case of theft.

“Eh? What? Oh—er—yes,—good evening,” he said, “good evening.” Behind them came a young woman in the glory of youth, and daintily silked, beautiful in face and form, with diamonds around her fair neck. She came in lightly, but stopped with a little gasp; then she laughed gaily and said:

“Why, I beg your pardon. Was it not curious? I thought I saw there behind your man”—she hesitated, but he must be a servant, she argued—”the shadow of great, white wings. It was but the light on the drapery. What a turn it gave me.” And she smiled again. With her came a tall, handsome, young naval officer. Hearing his lady refer to the servant, he hardly looked at him, but held his gilded cap carelessly toward him, and the stranger placed it carefully on the rack.

Last came the rector, a man of forty, and well-clothed. He started to pass the stranger, stopped, and looked at him inquiringly.

“I beg your pardon,” he said. “I beg your pardon,—I think I have met you?”

The stranger made no answer, and the hostess nervously hurried the guests on. But the rector lingered and looked perplexed.

“Surely, I know you. I have met you somewhere,” he said, putting his hand vaguely to his head. “You—you remember me, do you not?”

The stranger quietly swept his cloak aside, and to the hostess’ unspeakable relief passed out of the door.

“I never knew you,” he said in low tones as he went.

The lady murmured some vain excuse about intruders, but the rector stood with annoyance written on his face.

“I beg a thousand pardons,” he said to the hostess absently. “It is a great pleasure to be here,—somehow I thought I knew that man. I am sure I knew him once.”

The stranger had passed down the steps, and as he passed, the nurse, lingering at the top of the staircase, flew down after him, caught his cloak, trembled, hesitated, and then kneeled in the dust.

He touched her lightly with his hand and said: “Go, and sin no more!”

With a glad cry the maid left the house, with its open door, and turned north, running. The stranger turned eastward into the night. As they parted a long, low howl rose tremulously and reverberated through the night. The colonel’s wife within shuddered.

“The bloodhounds!” she said.

The rector answered carelessly:

“Another one of those convicts escaped, I suppose. Really, they need severer measures.” Then he stopped. He was trying to remember that stranger’s name.

The judge’s wife looked about for the draft and arranged her shawl. The girl glanced at the white drapery in the hall, but the young officer was bending over her and the fires of life burned in her veins.

Howl after howl rose in the night, swelled, and died away. The stranger strode rapidly along the highway and out into the deep forest. There he paused and stood waiting, tall and still.

A mile up the road behind a man was running, tall and powerful and black, with crime-stained face and convicts’ stripes upon him, and shackles on his legs. He ran and jumped, in little, short steps, and his chains rang. He fell and rose again, while the howl of the hounds rang louder behind him.

Into the forest he leapt and crept and jumped and ran, streaming with sweat; seeing the tall form rise before him, he stopped suddenly, dropped his hands in sullen impotence, and sank panting to the earth. A greyhound shot out of the woods behind him, howled, whined, and fawned before the stranger’s feet. Hound after hound bayed, leapt, and lay there; then silently, one by one, and with bowed heads, they crept backward toward the town.

The stranger made a cup of his hands and gave the man water to drink, bathed his hot head, and gently took the chains and irons from his feet. By and by the convict stood up. Day was dawning above the treetops. He looked into the stranger’s face, and for a moment a gladness swept over the stains of his face.

“Why, you are a nigger, too,” he said.

Then the convict seemed anxious to justify himself.

“I never had no chance,” he said furtively.

“Thou shalt not steal,” said the stranger.

The man bridled.

“But how about them? Can they steal? Didn’t they steal a whole year’s work, and then when I stole to keep from starving——” He glanced at the stranger.

“No, I didn’t steal just to keep from starving. I stole to be stealing. I can’t seem to keep from stealing. Seems like when I see things, I just must—but, yes, I’ll try!”

The convict looked down at his striped clothes, but the stranger had taken off his long coat; he had put it around him and the stripes disappeared.

In the opening morning the black man started toward the low, log farmhouse in the distance, while the stranger stood watching him. There was a new glory in the day. The black man’s face cleared up, and the farmer was glad to get him. All day the black man worked as he had never worked before. The farmer gave him some cold food.

“You can sleep in the barn,” he said, and turned away.

“How much do I git a day?” asked the black man.

The farmer scowled.

“Now see here,” said he. “If you’ll sign a contract for the season, I’ll give you ten dollars a month.”

“I won’t sign no contract,” said the black man doggedly.

“Yes, you will,” said the farmer, threateningly, “or I’ll call the convict guard.” And he grinned.

The convict shrank and slouched to the barn. As night fell he looked out and saw the farmer leave the place. Slowly he crept out and sneaked toward the house. He looked through the kitchen door. No one was there, but the supper was spread as if the mistress had laid it and gone out. He ate ravenously. Then he looked into the front room and listened. He could hear low voices on the porch. On the table lay a gold watch. He gazed at it, and in a moment he was beside it,—his hands were on it! Quickly he slipped out of the house and slouched toward the field. He saw his employer coming along the highway. He fled back in terror and around to the front of the house, when suddenly he stopped. He felt the great, dark eyes of the stranger and saw the same dark, cloak-like coat where the stranger sat on the doorstep talking with the mistress of the house. Slowly, guiltily, he turned back entered the kitchen, and laid the watch stealthily where he had found it; then he rushed wildly back toward the stranger, with arms outstretched.

The woman had laid supper for her husband, and going down from the house had walked out toward a neighbor’s. She was gone but a little while, and when she came back she started to see a dark figure on the doorsteps under the tall, red oak. She thought it was the new Negro until he said in a soft voice:

“Will you give me bread?”

Reassured at the voice of a white man, she answered quickly in her soft, Southern tones:

“Why, certainly.”

She was a little woman, and once had been pretty; but now her face was drawn with work and care. She was nervous and always thinking, wishing, wanting for something. She went in and got him some cornbread and a glass of cool, rich buttermilk; then she came out and sat down beside him. She began, quite unconsciously, to tell him about herself,—the things she had done and had not done and the things she had wished for. She told him of her husband and this new farm they were trying to buy. She said it was hard to get niggers to work, She said they ought all to be in the chain-gang and made to work. Even then some ran away. Only yesterday one had escaped, and another the day before.

At last she gossiped of her neighbors, how good they were and how bad.

“And do you like them all?” asked the stranger.

She hesitated.

“Most of them,” she said; and then, looking up into his face and putting her hand into his, as though he were her father, she said:

“There are none I hate; no, none at all.”

He looked away, holding her hand in his, and said dreamily:

“You love your neighbor as yourself?”

She hesitated.

“I try——” she began, and then looked the way he was looking; down under the hill where lay a little, half-ruined cabin.

“They are niggers,” she said briefly.

He looked at her. Suddenly a confusion came over her and she insisted, she knew not why.

“But they are niggers!”

With a sudden impulse she arose and hurriedly lighted the lamp that stood just within the door, and held it above her head. She saw his dark face and curly hair. She shrieked in angry terror and rushed down the path, and just as she rushed down, the black convict came running up with hands outstretched. They met in mid-path, and before he could stop he had run against her and she fell heavily to earth and lay white and still. Her husband came rushing around the house with a cry and an oath.

“I knew it,” he said. “It’s that runaway nigger.” He held the black man struggling to the earth and raised his voice to a yell. Down the highway came the convict guard, with hound and mob and gun. They paused across the fields. The farmer motioned to them.

“He—attacked—my wife,” he gasped.

The mob snarled and worked silently. Right to the limb of the red oak they hoisted the struggling, writhing black man, while others lifted the dazed woman. Right and left, as she tottered to the house, she searched for the stranger with a yearning, but the stranger was gone. And she told none of her guests.

“No—no, I want nothing,” she insisted, until they left her, as they thought, asleep. For a time she lay still, listening to the departure of the mob. Then she rose. She shuddered as she heard the creaking of the limb where the body hung. But resolutely she crawled to the window and peered out into the moonlight; she saw the dead man writhe. He stretched his arms out like a cross, looking upward. She gasped and clung to the window sill. Behind the swaying body, and down where the little, half-ruined cabin lay, a single flame flashed up amid the far-off shout and cry of the mob. A fierce joy sobbed up through the terror in her soul and then sank abashed as she watched the flame rise. Suddenly whirling into one great crimson column it shot to the top of the sky and threw great arms athwart the gloom until above the world and behind the roped and swaying form below hung quivering and burning a great crimson cross.

She hid her dizzy, aching head in an agony of tears, and dared not look, for she knew. Her dry lips moved:

“Despised and rejected of men.”

She knew, and the very horror of it lifted her dull and shrinking eyelids. There, heaven-tall, earth-wide, hung the stranger on the crimson cross, riven and blood-stained, with thorn-crowned head and pierced hands. She stretched her arms and shrieked.

He did not hear. He did not see. His calm dark eyes, all sorrowful, were fastened on the writhing, twisting body of the thief, and a voice came out of the winds of the night, saying:

“This day thou shalt be with me in Paradise!”

Host Commentary

PseudoPod, Episode 980-B for June 19th, 2025 also known in the United States at Juneteenth. Jesus Christ in Georgia by W.E.B. DuBois, narrated by Boocho McFly.

I’m Josh, Associate Editor here at Pseudopod, your host for this week. Incidentally, I’ll also be your host tomorrow for Episode 981, Robert Bloch’s “The Shambler from the Stars.” So, twice in one week. Yay!

One quick note, it’s been raining thundering for nearly a day here, and it’s not going to stop, so if that makes it into the audio, I apologize. Just think of it as mood.

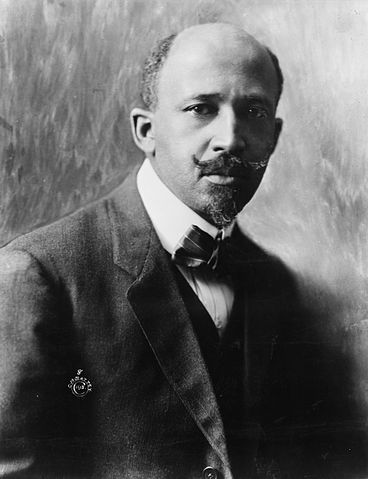

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. After completing graduate work at Harvard University, where he was the first African American to earn a doctorate, Du Bois rose to national prominence as a leader of the Niagara Movement, a group of black civil rights activists seeking equal rights. Du Bois was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. If you missed it, make sure to go into the back catalog (here or at NightLight) and listen to “The Comet” which is an amazing 1920 precursor to Day of the Triffids and 30 Days later.

“Jesus Christ in Georgia” was originally published in the 1911 Christmas issue of The Crisis in response to a lynching in Georgia. After a particularly bad one in Texas a few years later, the story was tweaked slightly and rereleased because it was relevant. And we wish it was a relic of the time period and did not remain relevant. One of the key legal approaches against lynching is arguing for the personhood of the victim of the lynching. If they’re a human being, then it’s a crime as human life is generally held in both religious and secular contexts to be sacred, which makes mob justice, which deprives these human beings of due process, one of the most monstrous collective actions we can take. That truth applies elsewhere in relevant ways, right now. I’ll just leave it at that.

This story deserves to be better recognized and more available under either name, which is why we are releasing the original story and Nightlight is releasing the retitled version. This way it’s easier to find regardless of which title is used. It combats erasure and gets the text of the story into more hands, now and in the future. Here in 2025, to paraphrase something I learned a long time ago, this story is an act of witness. The word “witness” means to testify: to tell the truth. To tell the truth is an act of responsibility as well as an expression of hope. Everyone deserves due process, and deserve the basic dignity of recognition as human beings who should receive equal protection under the law.

Boocho McFly is our narrator this week. Boocho Mcfly was created in a lab 40,000 years ago by the Annunaki, for the express purposes of being a substitute voice for Enki, who was at the time suffering through a cold that gave him a sore throat. Once his purpose was fulfilled, he was sealed away with a spell, and only allowed to reincarnate every 1,500 years, with the express goal of creation through the arts of music and crafting. He currently creates content under the name D’Shawn Payton and is available to narrate your dreams in real time. Audio Production is courtesy of Chelsea Davis. Oh, and be aware, just so you know we know and wanted to warn you about it, of the prolific use of the n-word in this story. Witnessing means we can’t look away.

And finally, just as a heads up, in the Outro I’m going to do two unorthodox things. First, I’m going to do the boilerplate up front, because asking you for money would feel incredibly crass to me immediately following the second unorthodox thing—but we’ll get to that in a minute.

In the meantime, we’ve got a story for you, and, with fear and trembling, I promise you it’s true.

Welcome back, everyone. Just as a reminder, I’m going the boilerplate first this week, so please stick around. I think it will make sense why I’m doing it that way this time when we get there.

PseudoPod is funded by you, our listeners, and we’re formally a non-profit. One-time donations are gratefully received and much appreciated, but what really makes a difference is subscribing. A $5 monthly Patreon donation gives us more than just money; it gives us stability and reliability and allows us to keep coming back, week after week.

If you can, please go to pseudopod.org and sign up by clicking on “feed the pod”. If you have any questions about how to support EA and ways to give, please reach out to us at donations@escapeartists.net.

Those of you that already support us: thank you! We literally couldn’t do it without you! It looks as though the Apple-taking-a-cut-from-Patreon thing may have been overturned, but just to be on the safe side, if you do want to sign up, do it through a browser – including the one actually ON your phone – as it might be cheaper than if you go through the official Patreon app.

And, if you can’t afford to support us financially, then please consider leaving reviews of our episodes, or generally talking about them on social media. We’d love to see you on Bluesky: find us at @pseudopod.org. If you like merch, you can also support us by buying goodies from the Escape Artists Voidmerch store. The link is in various places, including our latest social media posts.

PseudoPod is part of the Escape Artists Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, and this episode is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Download and listen to the episode on any device you like, but don’t change it or sell it. Theme music is by permission of Anders Manga.

PseudoPod knows It is a great pleasure to be here,—somehow I thought I knew that man. I am sure I knew him once.

Okay, still with me? Good. Time for the second unorthodox thing.

It had literally never occurred to me before today that I’d ever be talking about religion as part of my work at Pseudopod, but given the nature and context of today’s story, it’s unavoidable if we want an authentic understanding of how the story works and what DuBois was up to in writing it.

DuBois is usually remembered by historians and the public alike as a civil rights activist, and the religious aspects of his life and works has been understudied. I’ll read you a few paragraphs from a 2010 interview with author Edward J. Blum about his 2008 book, W. E. B. DuBois, American Prophet, which is the best work I’ve encountered on the subject.

Here’s what Blum said about DuBois:

Here was a man who defied the notion that God or Jesus was white; here was a man who prized the “souls of black folk” and what they had to teach the world; here was a man who taught to revere dark mothers and sisters; here was a man who challenged materialism, white supremacy, imperialism, and racial violence in explicitly religious terms. His voice became a prophetic call that rang in my heard. His spiritual wisdom stood in opposition to the narcissistic, greedy, and exploitative world of my youth. I decided to write a religious life and times of Du Bois as a way for me to unlearn the culture of white religious supremacy, to provide the spiritual sustenance that was kept from me during my white, middle-class upbringing. I hoped that others would be able to hear his prophetic calls as well.

Professionally, I felt drawn to write about religion in Du Bois’ because it filled two important historical gaps. First, he was basically ignored by American religious historians who tended to write more about Jonathan Edwards, Charles Finney, Billy Graham, or Martin Luther King Jr. I wondered about the religious insights of a man who refused to become a minister. I found that Du Bois’s life and insights probably tell us more about the power and place of religion in American society than any of these others. Second, American historians have written extensively about Du Bois but have basically ignored his interest in religion. I felt shocked to read book after book about The Souls of Black Folk that focused on the word “folk” in the title but not on “souls.” This struck me as a blind spot in the profession.

- E. B. Du Bois’ life and insights teach that religion has been (and continues to be) crucial in racial, economic, and gender matters. Whether the construction of whiteness or the social outcomes of segregation, notions of the sacred and the profane, of the eternal and abiding, of the holy and unholy are crucial to understanding American history. As a sociologist, historian, editor, poet, novelist, and activist, Du Bois always spoke to the religious histories and conditions of his topic at hand. So any reader who wants to understand American history must understand the power and presence of religion. And any reader who wants to be genuinely religious in an American context must take note of the past and present racial, gender, and class surroundings that create distance and breed alienation.

The biggest misconception, and one that has kept hidden from view Du Bois’ profound religious contributions, has been that Du Bois was simply an atheist or agnostic who cared little for religion. This is the dominant argument that stretches from the late 1950s to the most recent Pulitzer-Prize winning works of David Levering Lewis. To be blunt, Lewis was wrong. Du Bois wrote prayers for his students; he penned dozens of short stories imagining Jesus in American society; he crafted poems that were litanies; he attended church throughout most of his life; he created his own “Credo” that he used throughout his life as an emblem of self-identification; he gravitated toward Communism, but did so by claiming that Jesus was the first Communist; and by the end of his days, he wrote in his final autobiography that he loved living “spiritually” as much as physically. There is an avalanche of evidence that shows that Du Bois thought deeply about religion and religious issues, and to disregard that is to do him and our society a disservice.

We’ll put a link to the full interview in the show notes.

So, intense story. Besides the obvious, how’s this thing work? Unpacking all the scriptural and liturgical echoes DuBois put into this story would take forever, because they appear in almost every paragraph, but within the narrative they successfully stand on their own, and we get the point. Still, I want to comment briefly on three of them.

Nurse-maid who catches stranger’s cloak

First is the nurse-maid who flies down the stairs and catches the stranger’s cloak just after the Rector demonstrates he has neither ears to hear nor eyes to see. Her action is clear enough in its symbolic meaning, but DuBois is also borrowing elements from two episodes from the Gospels that anchor and significantly complicate the overall effect of the story. The first of these is the woman who, in hopes of being healed, surreptitiously touches Jesus’ cloak amidst the press of a teeming crowd, which appears in three of the four Gospels; and in Luke, which is the one I have open right now, it goes like this:

Luke 8:42 – 48 (Woman who touches cloak) (p. 1062)

- As Jesus went, the people pressed around him. And there was a woman who had had a discharge of blood for twelve years, and though she had spent all her living on physicians, she could not be healed by anyone. She came up behind him and touched the fringe of his garment, and immediately her discharge of blood ceased. And Jesus said, “Who was it who touched me?” When all denied it, Peter said, “Master, the crowds surround you and are pressing in on you!” But Jesus said, “Someone touched me, for I perceive that power has gone out from me.” And when the woman saw that she was not hidden, she came trembling, and falling down before him declared in the presence of all the people why she had touched him, and how she had been immediately healed. And he said to her, “Daught3er, your faith has made you well; go in peace.”

- There are many ways to interpret this passage, some of them very technical, but the poetical takeaway, for me, at least in the context of today’s episode, is that when nothing else has worked, sometimes we need to take a leap of faith—and that it’s not wrong, nor is it ever too late, to do so.

John 8 (Go and sin no more) (1096 – 7)

The second, from John’s Gospel, is about a woman caught in the act of adultery, whom the crowd wants to stone to death. The relevant part goes like this:

…they said to him, “Teacher, this woman has been caught in the act of adultery. Now in the Law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. So what do you say?” This they said to test him, that they might have some charge to bring against him. Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. And as they continued to ask him, he stood up and said to them, “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” And once more he bent down and wrote on the ground. But when they heard it, they went away one by one, beginning with the older ones, and Jesus was left alone with the woman standing before him. Jesus stood up and said to her, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” She said, “No one, Lord.” And Jesus said, “Neither do I condemn you; go, and from now on sin no more.”

There is obviously more than one takeaway from this, but it’s unavoidable that we’re meant to understand that none of us are clean in this—but also that we might be able to be made so again, maybe.

Farmer’s wife’s confession to stranger (73)

Next is the sudden Confession by the farmer’s wife:

- “She began, quite unconsciously, to tell him about herself—the things she had done, and had not done, and the things she had wished.”

- Many Christian denominations have some form of individual or collective confession, and the phrasing on DuBois’s part here is a deliberate allusion to an element generally common to that practice. The version I’m most familiar with goes like this:

Most merciful God,

We confess that we have sinned against you

In thought, word, and deed,

By what we have done,

And by what we have left undone.

We have not loved you with our whole heart;

We have not loved our neighbors as ourselves.

We are truly sorry and we humbly repent.

For the sake of your Son Jesus Christ,

Have mercy on us and forgive us;

That we may delight in your will,

And walk in your ways,

To the glory of your Name. Amen.

The Pillar of Fire (74)

Finally, that column of fire that throws great arms athwart the gloom and becomes a great burning, crimson cross:

- DuBois’s narrator says of the farmer’s wife that “A fierce joy sobbed up through the terror in her soul and then sank abashed as she watched the flame rise. Suddenly whirling into one great crimson column, it shot to the top of the sky” (74).

- DuBois is alluding to the Pillar of Fire from the book of Exodus, which functions in a literary way within that narrative was a significant symbol of God’s presence and guidance, but also in that narrative was literally a guide to the Jews during their time in the wilderness following their deliverance from Egypt. I think that’s important to know, because to most Americans today, if a story about a lynching has an image of a burning cross in it, we think immediately and primarily of the Klan. And I think DuBois means for us to go there. But the way the final episode is constructed suggests he meant to combine the horror of that image with something else more hopeful, and demonstrate the acting in the world of something more powerful than the world, capable of transforming even great pain and ugliness into something else. Which, even while agonizing in this context, seems to chime, in a terrible sort of way, with how the story actually ends, with the writhing, twisting body of the thief, who did not hear and could no longer see, yet whose gaze neither the woman, nor we, can escape.

There are more, many more, in this story, but you get the idea. So what exactly is “Jesus Christ in Georgia”?

Well, there’s obviously meant to be a lesson in it that reflects our own world, and our behavior in it, back at us and forces us to see it. There are a lot of types of story that do that, one of the most common being allegory. But this story isn’t an allegory: it’s a parable. Parables are sort of a hybrid of allegory and sermon in the form of a narrative, and both in the Gospels when Jesus used them in his ministry and when ministers today preach using stories of Jesus’ life, a common approach is to ask ourselves who we are in the story.

A hint: we’re never Jesus; and we’re rarely the Good Samaritan—often we’re the Jew; and we hope we might be the woman who touches Jesus’ cloak—but usually, the best we can hope for is that we’re the Priest who passes the Jew without helping him, represented here by the blind Rector who might see, but won’t. But my pessimism here is tempered slightly, potentially—I’m not sure—by the thought that maybe we’re really the farmer’s wife, who is the story’s final focalizer, and whose psychology the story most thoroughly explores.

I’m not fully sure what to make of the story, if I’m honest. I can’t tell whether DuBois’s final line is meant as darkly ironic—a condemnation, an indictment, really—or whether we’re meant to read into the horror the hope of redemption and renewal in the face of it. Either way, though, I think, the message is that we need to do better. In most flavors of Christianity, the general idea is that for whatever “doing better” means, we can’t actually do that on our own, and we need God’s help.

So, given the scriptural and liturgical echoes in this story, and its unfortunate and timely relevance in the year of our lord 2025, and the fact that I am a devout believer—I’m an Anglo-Catholic Episcopalian, if you were curious—I’m going to do something I would ordinarily never do in this context, at least on air: I’m going to pray, for all of us.

For those of you who aren’t Christians, or believers at all, or might even be bothered by this, I beg your indulgence, and hope you can at least appreciate the intention behind it. The need for repentance, grace, and healing is collective, and none of us can escape it.

In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost:

- O God our Father, whose Son forgave his enemies while he was suffering shame and death: Strengthen those who suffer for the sake of conscience; when they are accused, save them from speaking in hate; when they are rejected, save them from bitterness; when they are imprisoned, save them from despair; and to us your servants, give grace to respect their witness and to discern the truth, that our society may be cleansed and strengthened. This we ask for the sake of Jesus Christ, our merciful and righteous Judge. Amen.

- Grant, O God, that your holy and life-giving Spirit may so move every human heart [and especially the hearts of the people of this land], that barriers which dividuse us may crumble, suspicions disappear, and hatreds cease; that our divisions being healed, we may live in justice and peace; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

- Look with pity, O heavenly Father, upon the people in this land who live with injustice, terror, disease, and death as their constant companions. Have mercy upon us. Help us to eliminate our cruelty to these our neighbors. Strengthen those who spend their lives establishing equal protection of the law and equal opportunities for all. And grant that every one of us may enjoy a fair portion of the riches of this land; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

About the Author

W.E.B. DuBois

William Edward Burghardt “W. E. B.” Du Bois (February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author, writer and editor.

About the Narrator

Boocho McFly

Boocho McFly was created in a lab 40,000 years ago by the Annunaki, for the express purposes of being a substitute voice for Enki, who was at the time suffering through a cold that gave him a sore throat. Once his purpose was fulfilled, he was sealed away with a spell, and only allowed to reincarnate every 1,500 years, with the express goal of creation through the arts of music and crafting. He currently creates content under the name D’Shawn Payton and is available to narrate your dreams in real time.

About the Artist