PseudoPod 967: Two’s Company, Three Might Be A Sign of Demonic Possession

Show Notes

Also narrated by Pine Gonzalez: A Relationship in Four Haircuts, by Ai Jiang

Two’s Company, Three Might Be a Sign of Demonic Possession

by Audrey Zhou

You didn’t take the usual precautions when Lin died.

You would find out later how it happened—slippery tile floor, the trials of installing a new shower curtain rod, and the surprisingly fragile vertebrae going up Lin’s neck—but in the moment all you knew was that there was a crash. When Lin didn’t respond after you called her name from the kitchen, you had enough wherewithal to grab the salt before stumbling to the bathroom, but not enough to keep from spilling a third of it all over yourself when you saw her body.

There was no pulse—your face twisted at the angle of her neck and all the blood, and you knew there couldn’t be—but you checked anyway. Then you took a deep breath and ignored every lesson you’d ever learned about how to conduct a proper resurrection.

You didn’t report the death because accidental deaths always meant the process of obtaining a permit would take months; you weren’t sure how long Lin could stay in a resurrectable state. You didn’t call anyone else either, though resurrections were never a solitary affair; while all of your necromancer friends would have happily double-checked your work, they would have insisted you do this the legal way.

At the moment, you weren’t concerned with safe or legal.

Instead you got your sword, unsharpened but marked with characters to expel evil—a spiritual instrument, to help you stay in the land of the living—and walked yourself back to the kitchen for the chicken you’d been marinating—it had been your thanks to Lin for her help with the DIY renovations to your apartment, but it would be an offering now, for safe passage into the land of the dead. Your shaking hands made a clumsy circle of salt on the ground, to contain anything that might take advantage of what you were about to do and cross over to life.

You tethered your own spirit into the sword to ground yourself in this world, and then you were free to transform your voice so it had a liminal quality, until it was something that transcended borders—something that could coax someone back to life—and you began the ritual that would call Lin back.

It was hard to say how much time passed—you were not in either place, really, in this state, and time was funny in an in-between place like that. All you knew was that your voice was raspy and your throat was raw from chanting when you finally sensed Lin’s body stirring, her breath heaving with the force of a storm as her spirit stuttered back into her body.

Then you were crying and Lin was crying. Her voice was still her own when she pulled you into a fierce hug and said, “Ailing, oh god, thank you, what happened,” and the gash on her neck pulled itself into a white seamed scar. You were grateful that Mr. Yang next door hadn’t noticed anything, and that if he had, he’d decided not to report you for an unauthorized resurrection.

It was a lot at once, is the point, which is why it was forgivable that you didn’t notice that the salt circle had perhaps not been completely closed when you’d started summoning, that Lin was maybe only entirely herself on the surface level.

Why it was forgivable that you didn’t notice me—that I was there, too.

Spirits are sticky. Have to be, to stay in a skin. It helps in their manipulation: it’s easier to call something back from the dead if it wants to return.

The issue is that things can get stuck to them. Maybe it’s more accurate to say that, sometimes, things will latch on and the spirit won’t know better than to be sticky, to let it happen.

Say a person comes back from the dead with a vision of their deceased grandparents. Maybe a person comes back with a vision of what death turned their deceased grandparents into—the other side contains any number of things: ghosts, memories, demons. Hauntings.

Most of that stuff is harmless—visions and ghosts disappear in a few days like a dream, half-formed and hazy and barely remembered. They don’t linger, don’t lurk around the border of life. They aren’t waiting for something to give or keeping watch for a way to slip through—a resurrection is always an excellent doorway.

Sometimes, though, a person comes back with something like me.

We—you, Lin, and I, where I was tucked into the scar on her neck, the only evidence of the accident now that your bathroom had been deep-cleaned—headed to your doctor friend.

“I’m not an official doctor yet,” Sun your doctor friend said modestly as he welcomed us into the apartment. “Come in, please. What am I looking for?”

He was sweet. He explained to Lin that he was specializing in resurrection recovery, and you assured her that though he was only a student, he was very good. Sun was discreet, too—he nodded solemnly as you explained the situation with the air of someone used to these under-the-table check-ups.

He brought us to the living room, where you paced around the coffee table as he sat Lin on the couch. He took out an instrument case and produced an erhu.

“I don’t work with the physical side of things much,” he said to Lin, charmingly sheepish. “Just the spirit side. You said you hit your head?”

He drew the bow between the strings and I experienced the ingenuity of his skill: he was calling to Lin’s spirit—though with an instrument rather than a voice, as you did—and identifying any abnormalities through how it responded to the sound.

“Well, it was my neck that—you know. But I hit my head going down.”

You walked another circle around the table. “Is it possible something latched on when she came back? Is it possible I didn’t bring all of her back? There wasn’t the time to do it the usual way.”

“I feel fine,” Lin insisted, to no avail, as Sun played another strain.

I was unused to the way I was supposed to hide in this realm, where everyone was warm and breathing, but I knew I needed to do something. Sun was eyeing the scar on Lin’s neck so I slipped to the bone of Lin’s skull and then dipped deeper. Her blood was hot, hotter still when I curled myself into a blood cell and disguised myself in the flow of her cerebral arteries.

Sun was good at what he did, but he’d said it himself—he didn’t work with the physical much. I wound myself so deep into Lin’s brain that I didn’t flinch when the next melody came, so deep Sun wouldn’t be able to register me as anything but another part of her anatomy.

Deep enough Lin couldn’t register me as what I was, either.

“Maybe we should go to a specialist—no offense, Sun,” you said.

“None taken.”

Lin shook her head. “You only just got licensed, Ailing, and you know that people have lost their licenses for less. Resurrecting a pet without permission is one thing, but a person?”

Sun motioned for quiet. You fell silent as he finished his check-up, his last notes long and quiet.

“Maybe Ailing could stay with you, Lin. Just for a bit, to keep an eye out for if anything changes,” Sun said finally. “Everything sounds fine—the scarring is a good sign that the resurrection went well, at least. But better safe than sorry, right?”

I learned a lot about Lin as we cohabited. Memory informed a lot about a person. So did the spaces they liked to occupy.

I got well-acquainted with her temporal lobe and found tangible pieces of all of that in her room: a photograph with her parents from her graduation on the desk, an overwhelm of plants choking out the sunlight trying to stream through the window, a dress she’d borrowed from you and forgotten to return buried in the depths of her closet. I learned that she worked at a plant science lab—no spirit stuff involved—and hated the snow, and that her favorite food was soup dumplings.

I picked up on things she didn’t know herself—the blurred impressions of life she’d had as a child, stored in her cortex as sense-memories; the dreams rumbling around her head that she forgot come morning.

You were there, too. You’d been a frequent feature in Lin’s temporal lobe once she’d hit twenty, after meeting in a botany class for Lin’s major that you took as an elective, and now you were taking Sun’s advice seriously—you were over at the apartment three times a week and always looking at Lin, as if you could peer right through her and see me.

“I’m really fine,” Lin said to you, the weekend after the accident.

It was movie night, or at least it was supposed to be, but you were looking more at her than at the rom-com. Lin thought all of your sidelong glances were solely from worry, but I wasn’t so sure.

I don’t think you’d been in love with her back in college, but you weren’t exactly subtle now.

You were anxious. “You don’t feel any different, right? You remember, Mr. Yang? We all thought his sister came back fine and it turned out to be their dead aunt masquerading as her. How does that even happen?”

Lin winced. “I wouldn’t worry about that,” she said. “I really, truly think you’d notice if that happened to me.”

“You’d think Mr. Yang would have noticed,” you muttered, but you relaxed when Lin laughed at you, endeared.

And then I got curious.

I went back to Lin’s cortex and made the line of your neck more swooping and elegant, when she processed it. Twisted my way into Lin’s limbic system to hike her emotions a little higher, filtered something novel and new into the situation. Stretched down to her heart to make it beat faster.

Made her wonder, as Main Character and Love Interest kissed on screen, what that might be like with the two of you.

Nothing happened that night, at least explicitly—as you always did, you left once the movie finished and hugged Lin goodbye. No kisses, no confessions. But I knew there was a new thing humming between the two of you, thrilling and inescapable.

“Thanks for having me over,” you said, standing by the door.

“Of course,” Lin told you, clearing her throat to get it out properly, before—all on her own, no input from me—she blushed.

I think that was when you reframed the situation in your head, the flushing and the new awkwardness. When you noticed how Lin couldn’t quite meet your gaze; registered how, for once, she might have noticed you looking at her. Might even be looking back.

At the time, I watched your own cheeks go rosy and your mouth grow slack with surprise. I didn’t realize until later that you’d been suspicious, even then.

A tab still open on your phone, even now, from some famous necromancer’s blog of tips and tricks:

Possessions are tricky. Treatment and identification always depend on what’s doing the possessing and who’s being possessed. In school, we learn about the usual signs (changes in appearance, disturbed sleep, lapses in memory), but textbooks can’t teach us everything. Over the years, one of the things I’ve learned to look for is changes in behavior.

I know everyone says it, but I don’t mean speaking in ancient languages or sleep-walking. I mean the small stuff, the intimacies. A possession might get the big things right, but as they say, the devil is in the details. Does the host fold their shirts in a new way? Have they always spiced their food like that?

Did you know them, really? Are you sure?

You and Lin grew closer. I grew more curious.

I stopped interfering with her feelings for you, but I experimented with other ways of control. I dove back into Lin’s memories to learn her mannerisms better. I practiced when she slept and wouldn’t notice: tugged her mouth into a smile, flexed her fingers into a fist, spoke out loud to get a feel for how my words sounded in her voice.

When Lin went to the lab for work, I slipped around her head, testing how much force I needed to put into a suggestion for it to take. It was easier to nudge her into decisions she wanted to make—she invited her favorite coworkers out to brunch over the weekend with no hesitation. It took a whole afternoon to figure out how to twist the neurons in her prefrontal lobe so she’d pour pesticides into a soil sample that had been prepped for seeds.

Maybe it went both ways—I was reluctant, an emotion that could have only come from her, when she finally listened to me and nothing sprouted.

You came over more frequently. You still worried about Lin’s health but said less about it outright, though you were always giving us searching looks. You did subtle tests to double-check if Lin really was entirely herself—“Do you remember the name of that building they did all the career fairs in?”— so I practiced transitioning the reins over to Lin, to pass them. Practiced, also, getting control back when I wanted it.

One night, the two of you went out to dinner. I’d decided it was Lin’s turn: I was exploring, trying to find where in Lin’s brain her unconsciousness cradled its thoughts, when I felt her heart rate pick up.

There was a strange look on your face, the kind you wore when conducting one of your possession tests, and at first I thought that was why. Then I tuned in and realized you were saying: “You’ve been acting differently lately.”

“Bad different?” Lin asked, before I could stop her. “I’ve felt—I don’t know. Yeah. Different is a word for it.”

She was thinking about you, but she was also remembering the times she’d woken up in the night for seemingly no reason at all.

“Not a bad different,” you told her. “I’ve just noticed that we’ve been hanging out a lot.”

“You’re the one who insisted on watching over me,” Lin said. “Regretting it now?”

“Of course not. I just think there’s a difference in how we’re hanging out now versus before the—accident.”

Lin tensed. I tried damage control and took over to ask, “You think everything is because of that?”

You winced, picking up on her annoyance despite my efforts to keep her voice even. “Resurrection is an imperfect process.” You were careful not to say the word possession but we all heard it.

I didn’t know how to convince you that everything was fine. I panicked. I coaxed the blood circulating in Lin’s ears up to the surface in the flush that meant she was embarrassed, and I guided her further over the table, giving you plenty of time to lean in when you noticed how she was looking at your mouth.

You responded as if choreographed: you reddened and hissed, “We’re in public!” and yet you didn’t move away. You couldn’t remain suspicious when faced with something you wanted so badly—from the look on your face, you’d forgotten to think at all. You were the one who kissed her when I said in her voice, “I know my own feelings.”

The two of you started dating officially after that, and I thought that was the end of it. Maybe that was the problem—that I grew complacent, sloppy, less careful with the choices I nudged Lin into.

Maybe it was just that even though Lin knew you, that didn’t necessarily mean I knew you. Just because I couldn’t tell you were suspicious didn’t mean your suspicions had actually gone away.

Three months after I’d first inhabited Lin’s body, you gave up subtlety and said, “I think you might be possessed.”

I couldn’t figure out what course of action was least painful. Did I deflect? Did I deny it? Did I let you do whatever experiment you wanted to and hope I would remain undetected?

In the time it took me to decide, Lin replied, mouth twisted, “Yes, I think you might be right.”

Exorcisms were the standard treatment for possessions: purge the intruder from the host. Required studying for all aspiring necromancers—there were no number of things that could slip through the cracks when working with the dead.

But what was a host, really?

It was Lin’s body, sure, but a body was just a body. You couldn’t see me, underneath Lin’s skin, but you could see the effects: the times she laughed at something uncharacteristically and her smile slanted into something unfamiliar; the times you’d mention an old friend and I hadn’t dug deep enough into Lin’s memories to feign recognition on her face, when you brought them up.

Maybe it was Lin’s body, but it wasn’t really her that was driving, anymore.

An exorcism was a lot like a resurrection.

You had the time to prepare this time, and you made full use of it. You made a giant salt circle around Lin’s whole apartment to contain me; I tried to coax Lin’s body to sleepwalk out in the night and she woke up with burns on her toes, where she’d broken the line. The two of you bandaged her feet and made roast duck together for the offering. You bought incense.

The day of, you got out your sword again and asked Sun to be available, in case something went wrong.

“Don’t actually come over though,” you told him, over the phone. “I don’t want to implicate you.” Unauthorized exorcisms weren’t as bad as unauthorized resurrections, but you weren’t taking any chances on Sun.

You anchored yourself with your sword and Lin drank the tea you made for her, specially brewed to help ease any strain the process might put on her body. She sat on the floor, cross-legged, in a smaller salt circle you’d made for extra security. You began chanting.

I braced myself for it, to return home—death wasn’t welcoming, but it wasn’t unkind, either. I could bear it. Your voice got louder and I could feel something tugging, a separation. There was screaming. I still don’t know who it was, if it was Lin or I, or even you. I didn’t know anything for a long time.

In the aftermath, you crumpled on the floor, exhausted. Lin’s body was on the floor too, fingertips brushed up against the salt.

You were looking at her hands, the unburnt skin, when you said, “Did it work?”

I sat up. I was warm all over—blood, flesh, bone—and I was alone. It was solely myself in control of the breaths I was taking, in the way I met your hopeful gaze. Even when Lin had been asleep, I’d had to be careful not to wake her. But now it was just me.

It was a strange feeling to possess a body like this. To really, truly possess it, to know it.

“Yes,” I told you, wondering, understanding how it felt for myself—myself, alone!— to feel wonder. “Yes, it did.”

As humans do, we move on after the accident, after the exorcism—after everything.

You and I get along well, for the most part. We move into an apartment with no memories of either incident and you make coffee for the both of us every morning. I make breakfast. We go on dates and talk about adopting a dog, and sometimes at night you remember the screaming.

I’m better at being Lin now—her memories are mine, now that her brain is—but I’m not perfect. I slip up and say the wrong thing when I should kiss you. Kiss you when I should say something comforting.

You look at Lin and you wonder sometimes, who you are looking at. Some days you are closer to seeing me than others.

Today is one of those days. You make coffee as usual, but you can’t look me in the eyes. You can only glance at me sidelong, lost and searching, and you tell me you slept weird, when I ask what’s wrong. I put my hand on your shoulder and you flinch, then look guilty for it.

I make bacon and eggs with Lin’s muscle memory, but I haven’t exactly inherited her taste buds—salt doesn’t hurt me anymore, but I still don’t like it. I tell you it’s because I want to eat healthier, the first time you ask, but your eyes still zero in on my plain eggs.

“I’d better get going,” you say, when your own plate is only half-finished. “New case at work, I’ll probably have to stay late. Daughter wants to see her parents again. I’ll see you later though, alright?”

You kiss me goodbye on the cheek, not the mouth. That’s fine. Tomorrow I’ll still be Lin, and tomorrow I’ll do a better job.

I smile at you, the way I learned from her. “I’ll be waiting.”

Host Commentary

PseudoPod, Episode 967 for March 21st, 2025.

Two’s Company, Three Might Be A Sign of Demonic Possession by Audrey Zhou

Narrated by Pine Gonzalez; hosted by Kat Day audio by Chelsea Davis

Hey everyone, hope you’re all doing okay! Spring is here in the northern hemisphere, and things are… waking up and… pushing their way out of the ground…

I’m Kat, Deputy Editor at PseudoPod, your host for this week, and I’m excited to tell you that we have Two’s Company, Three Might Be A Sign of Demonic Possession. This story is a PseudoPod Original.

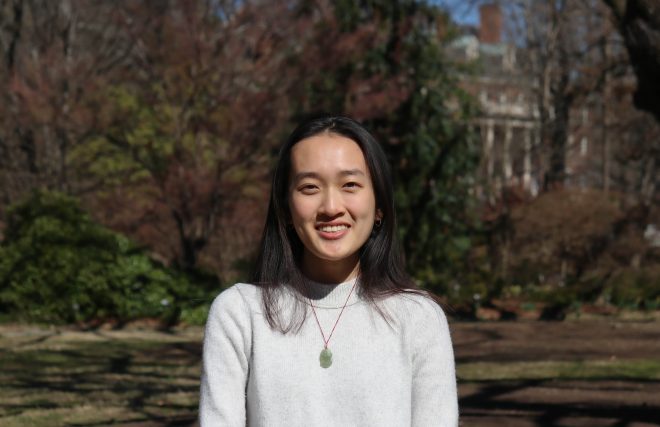

Author bio:

Audrey Zhou is a Chinese American writer from North Carolina, where she studies computer science, statistics, and creative writing at UNC-Chapel Hill. Her short fiction has been published in Strange Horizons and Orion’s Belt and is forthcoming in the Silk and Sinew anthology from Bad Hand Books. When not writing, she likes to draw, watch bad TV with her friends, and curate oddly specific playlists of music. Find her @audreyzhou.bsky.social on Bluesky.

Narrator bio:

Pine Gonzalez is a Puerto Rican/Chinese American writer and voice actor from the Chicagoland area. They are the creator of the podcasts Tales from the Fringes of Reality and Forged Bonds, both of which also feature their voice. When not writing or working at a bookstore they can be found listening to as many audio dramas as they are able to and playing with their dog Athena.

Before we continue, this story is told in second-person PoV and has a content warning for intimate partner death. Sort of. Not exactly. It… er… this will make sense soon… but anyway, just in case, if that’s tough for you, maybe skip this one.

And now we have a story for you. And we promise you, it’s true.

Well done, you’ve survived another story. What did you think of Two’s Company, Three Might Be A Sign of Demonic Possession, by Audrey Zhou? If you’re a Patreon subscriber, we encourage you to pop over to our Discord channel and tell us.

One of the, many, nice things about having children is that, fairly regularly, they’ll pull you up on some thing that you’ve been taking for granted for years and you’ll suddenly see it with new eyes. Recently, my youngest asked me to explain the phrase, ‘six of one, half-dozen of the other,’ and that led to a long conversation about how, often, even usually, fault is not clear-cut. We like to imagine that there’s a goodie and a baddie, but real life is never so tidy. There’s usually a split. It might not be half and half, it might be… oh… eight to four, or ten to twelve, or even one to eleven, but there’s usually something on both sides. A smear of grey in the light, a flash of silver in the dark.

And so it is here, in this story. A demon – for want of a better word – sneaks back with Lin, hides in the scar on her neck and gradually possesses her. That’s bad, right? Definitely baddie behaviour.

But it’s a nice demon. It watches the people, doesn’t wish anyone any harm. Encourages Lin to explore her feelings for Ailing, who clearly already has feelings for Lin. That’s… sort of sweet, right?

And the exorcism wasn’t the demon’s idea, was it? It was Ailing who said, “I think you might be possessed.” The demon even tried to get out of it by encouraging Lin to sleepwalk. When that failed they braced to be ejected, accepted their fate. They didn’t fight it.

They didn’t expect Lin to go while they stayed. That wasn’t planned. But once it had happened well, what could they do but get on with things? They’d stolen a body but… it was an accident. Just an accident. Mostly.

“Tomorrow I’ll still be Lin, and tomorrow I’ll do a better job.”

…

So… two things. One is the greyness of the demon’s goodness or badness, depending on your point of view, and that’s everything here, isn’t it? Point of view? This is a story told in second-person and it’s one of those cases where that is exactly the right choice, because it’s about the demon but it’s also about Ailing… wanting something.

Which is the second thing. Ailing wanted Lin and so she got her. She fulfilled her own prophecy. She, the necromancer, or resurrectionist, or exorcist, or whatever you want to call it, got… what she wanted all along. Was that Lin? Or wasn’t it? Does it matter? Hard to be sure, isn’t it.

But the demon is trying to be better. Trying to do a better job. Aren’t we all?

Best draw a line, step over it, and do the best we can with what we’ve got now. We’ve none of us any other choice, have we?

Spectacular work from the supremely talented Audrey Zhou and a marvellous narration from Pine Gonzalez. Thank you, both.

Now, onto the subject of subscribing and support: PseudoPod is funded by you, our listeners, and we’re formally a non-profit. One-time donations are gratefully received and much appreciated, but what really makes a difference is subscribing. A $5 monthly Patreon donation gives us stability and allows us to keep coming back, week after week. And you wouldn’t want us to stop coming back, would you? Would you?

If you can, please go to pseudopod.org and sign up by clicking on “feed the pod”. If you have any questions about how to support EA and ways to give, please reach out to us at donations@escapeartists.net.

Those of you that already support us: thank you! We literally couldn’t do it without you! And a reminder that Apple have changed the way charging works through App Store apps, and, long story short: if you are signing up you should go through a browser – including one on actually ON your phone – it’ll be cheaper than if you go through the official Patreon app.

And, if you can’t afford to support us financially, and we get it, the world is… on fire… then please consider leaving reviews of our episodes, or just talking about them on whichever form of social media you are battling demons on this week. We have a Bluesky account: find us at @pseudopod.org. If you like merch, you can also support us by buying goodies from the Escape Artists Voidmerch store. The link is in various places, including our latest social media posts.

PseudoPod is part of the Escape Artists Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, and this episode is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Download and listen to the episode on any device you like, but don’t change it or sell it. Theme music is by permission of Anders Manga.

Next week we have… Tree of the Forest Seven Bells Turns the World Round Midnight by Sheree Renée Thomas, narrated by Premee Mohamed and hosted by Scott.

And finally, PseudoPod, and Your Affectionate Uncle Screwtape, know

“Readers are advised to remember that the devil is a liar.”

See you soon, folks, take care, stay safe.

About the Author

Audrey Zhou

Audrey Zhou is a Chinese American writer from North Carolina, where she studies computer science, statistics, and creative writing at UNC-Chapel Hill. Her short fiction has been published in Strange Horizons and Orion’s Belt and is forthcoming in the Silk and Sinew anthology from Bad Hand Books. When not writing, she likes to draw, watch bad TV with her friends, and curate oddly specific playlists of music. Find her @aud_zhou on Twitter and @audreyzhou.bsky.social on Bluesky

About the Narrator

Pine Gonzalez

Pine Gonzalez is a Puerto Rican/Chinese American writer and voice actor from the Chicagoland area. They are the creator of the podcasts Tales from the Fringes of Reality and Forged Bonds, both of which also feature their voice. When not writing or working at a bookstore they can be found listening to as many audio dramas as they are able to and playing with their dog Athena.