PseudoPod 958: The Shout

The Shout

By Robert Graves

When we arrived with our bags at the asylum cricket ground, the chief medical officer, whom I had met at the particular house where I was staying, came up. I told him that I was only scoring for the Lampton team today (I had broken a finger the week before, keeping wicket on a bumpy pitch). He said: “Oh, then you’ll have an interesting companion.”

“The other scoresman?” I asked.

“Crossley is the most intelligent man in the asylum,” answered the doctor, “a wide reader, a first-class chess-player, and so on. He seems to have travelled all over the world. He’s been sent here for delusions. His most serious delusion is that he’s a murderer, and his story is that he killed two men and a woman at Sydney, Australia. The other delusion, which is more humorous, is that his soul is split in pieces—whatever that means. He edits our monthly magazine, he stage-manages our Christmas theatricals, and he gave a most original conjuring performance the other day. You’ll like him.”

He introduced me. Crossley, a big man of forty or fifty, had a queer, not unpleasant, face. But I felt a little uncomfortable, sitting next to him in the scoring box, his black-whiskered hands so close to mine. I had no fear of physical violence, only the sense of being in the presence of a man of unusual force, even perhaps, it somehow occurred to me, of occult powers.

It was hot in the scoring box in spite of the wide window. “Thunderstorm weather,” said Crossley, who spoke in what country people call a “college voice,” though I could not identify the college. “Thunderstorm weather makes us patients behave even more irregularly than usual.”

I asked whether any patients were playing.

“Two of them, this first wicket partnership. The tall one, B. C. Brown, played for Hants three years ago, and the other is a good club player. Pat Slingsby usually turns out for us too—the Australian fast bowler, you know—but we are dropping him today. In weather like this he is apt to bowl at the batsman’s head. He is not insane in the usual sense, merely magnificently ill-tempered. The doctors can do nothing with him. He wants shooting, really.” Crossley began talking about the doctor. “A good-hearted fellow and, for a mental-hospital physician, technically well advanced. He actually studies morbid psychology and is fairly well-read, up to about the day before yesterday. I have a good deal of fun with him. He reads neither German nor French, so I keep a stage or two ahead in psychological fashions; he has to wait for the English translations. I invent significant dreams for him to interpret; I find he likes me to put in snakes and apple pies, so I usually do. He is convinced that my mental trouble is due to the good old ‘antipatemal fixation’—I wish it were as simple as that.”

Then Crossley asked me whether I could score and listen to a story at the same time. I said that I could. It was slow cricket.

“My story is true,” he said, “every word of it. Or, when I say that my story is ‘true,’ I mean at least that I am telling it in a new way. It is always the same story, but I sometimes vary the climax and even recast the characters. Variation keeps it fresh and therefore true. If I were always to use the same formula, it would soon drag and become false. I am interested in keeping it alive, and it is a true story, every word of it. I know the people in it personally. They are Lampton people.”

We decided that I should keep score of the runs and extras and that he should keep the bowling analysis, and at the fall of every wicket we should copy from each other. This made storytelling possible….

Richard awoke one morning saying to Rachel: “But what an unusual dream.”

“Tell me, my dear,” she said, “and hurry, because I want to tell you mine.”

“I was having a conversation,” he said, “with a person (or persons, because he changed his appearance so often) of great intelligence, and I can clearly remember the argument. Yet this is the first time I have ever been able to remember any argument that came to me in sleep. Usually my dreams are so different from waking that I can only describe them if I say: ‘It is as though I were living and thinking as a tree, or a bell, or middle C, or a five-pound note; as though I had never been human. Life there is sometimes rich for me and sometimes poor, but I repeat, in every case so different, that if I were to say: ‘I had a conversation,’ or ‘I was in love,’ or ‘I heard music,’ or ‘I was angry, it would be as far from the fact as if I tried to explain a problem of philosophy, as Rabelais’s Panurge did to Thaumast, merely by grimacing with my eyes and lips.’

“It is much the same with me,” she said. “I think that when I am asleep I become, perhaps, a stone with all the natural appetites and convictions of a stone. ‘Senseless as a stone’ is a proverb, but there may be more sense in a stone, more sensibility, more sensitivity, more sentiment, more sensibleness, than in many men and women. And no less sensuality,” she added thoughtfully.

It was Sunday morning, so that they could lie in bed, their arms about each other, without troubling about the time; and they were childless, so breakfast could wait. He told her that in his dream he was walking in the sand hills with this person or persons, who said to him: “These sand hills are a part neither of the sea before us nor of the grass links behind us, and are not related to the mountains beyond the links. They are of themselves. A man walking on the sand hills soon knows this by the tang in the air, and if he were to refrain from eating and drinking, from sleeping and speaking, from thinking and desiring, he could continue among them forever without change. There is no life and no death in the sand hills. Anything might happen in the sand hills.”

Rachel said that this was nonsense, and asked: “But what was the argument? Hurry up!”

He said it was about the whereabouts of the soul, but that now she had put it out of his head by hurrying him. All that he remembered was that the man was first a Japanese, then an Italian, and finally a kangaroo.

In return she eagerly told her dream, gabbling over the words. “I was walking in the sand hills; there were rabbits there, too; how does that tally with what he said of life and earth? I saw the man and you walking arm in arm towards me, and I ran from you both and I noticed that he had a black silk handkerchief; he ran after me and my shoe buckle came off and I could not wait to pick it up. I left it lying, and he stooped and put it into his pocket.”

“How do you know that it was the same man?” he asked.

“Because,” she said, laughing, “he had a black face and wore a blue coat like that picture of Captain Cook. And because it was in the sand hills.”

He said, kissing her neck: “We not only live together and talk together and sleep together, but it seems we now even dream together.”

So they laughed.

Then he got up and brought her breakfast.

At about half past eleven, she said: “Go out now for a walk, my dear, and bring home something for me to think about: and be back in time for dinner at one o’clock.”

It was a hot morning in the middle of May, and he went out through the wood and struck the coast road, which after half a mile led into Lampton.

(“Do you know Lampton well?” asked Crossley. “No,” I said, “I am only here for the holidays, staying with friends.”)

He went a hundred yards along the coast road, but then turned off and went across the links: thinking of Rachel and watching the blue butterflies and looking at the heath roses and thyme, and thinking of her again, and how strange it was that they could be so near to each other; and then taking a pinch of gorse flower and smelling it, and considering the smell and thinking. “If she should die, what would become of me?” and taking a slate from the low wall and skimming it across the pond and thinking, “I am a clumsy fellow to be her husband”; and walking towards the sand hills, and then edging away again, perhaps half in fear of meeting the person of their dream, and at last making a half circle towards the old church beyond Lampton, at the foot of the mountain.

The morning service was over and the people were out by the cromlechs behind the church, walking in twos and threes, as the custom was, on the smooth turf. The squire was talking in a loud voice about King Charles, the Martyr: “A great man, a very great man, but betrayed by those he loved best,” and the doctor was arguing about organ music with the rector. There was a group of children playing ball. “Throw it here, Elsie, No, to me, Elsie, Elsie, Elsie.” Then the rector appeared and pocketed the ball and said that it was Sunday; they should have remembered. When he was gone they made faces after him.

Presently a stranger came up and asked permission to sit down beside Richard; they began to talk. The stranger had been to the church service and wished to discuss the sermon. The text had been the immortality of the soul: the last of a series of sermons that had begun at Easter. He said that he could not grant the preacher’s premise that the soul is continually resident in the body. Why should this be so? What duty did the soul perform in the daily routine task of the body? The soul was neither the brain, nor the lungs, nor the stomach, nor the heart, nor the mind, nor the imagination. Surely it was a thing apart? Was it not indeed less likely to be resident in the body than outside the body? He had no proof one way or the other, but he would say: Birth and death are so odd a mystery that the principle of life may well lie outside the body which is the visible evidence of living. “We cannot,” he said, “even tell to a nicety what are the moments of birth and death. Why, in Japan, where I have travelled, they reckon a man to be already one year old when he is born; and lately in Italy a dead man—but come and walk on the sand hills and let me tell you my conclusions. I find it easier to talk when I am walking.”

Richard was frightened to hear this, and to see the man wipe his forehead with a black silk handkerchief. He stuttered out something. At this moment the children, who had crept up behind the cromlech, suddenly, at an agreed signal, shouted loud in the ears of the two men: and stood laughing, The stranger was startled into anger; he opened his mouth as if he were about to curse them, and bared his teeth to the gums. Three of the children screamed and ran off. But the one whom they called Elsie fell down in her fright and lay sobbing. The doctor, who was near, tried to comfort her. “He has a face like a devil,” they heard the child say.

The stranger smiled good-naturedly: “And a devil I was not so very long ago. That was in Northern Australia, where I lived with the black fellows for twenty years. ‘Devil’ is the nearest English word for the position that they gave me in their tribe; and they also gave me an eighteenth-century British naval uniform to wear as my ceremonial dress. Come and walk with me in the sand hills and let me tell you the whole story. I have a passion for walking in the sand hills: that is why I came to this town … My name is Charles.”

Richard said: “Thank you, but I must hurry home to my dinner.”

“Nonsense,” said Charles, “dinner can wait. Or, if you wish, I can come to dinner with you. By the way, I have had nothing to eat since Friday. I am without money.”

Richard felt uneasy. He was afraid of Charles, and did not wish to bring him home to dinner because of the dream and the sand hills and the handkerchief: yet on the other hand the man was intelligent and quiet and decently dressed and had eaten nothing since Friday; if Rachel knew that he had refused him a meal, she would renew her taunts. When Rachel was out of sorts, her favorite complaint was that he was overcareful about money; though when she was at peace with him, she owned that he was the most generous man she knew, and that she did not mean what she said; when she was angry with him again, out came the taunt of stinginess: “Ten-pence-halfpenny,” she would say, “tenpence-halfpenny and threepence of that in stamps”; his ears would burn and he would want to hit her. So he said now: “By all means come along to dinner but that little girl is still sobbing for fear of you. You ought to do something about it.”

Charles beckoned her to him and said a single soft word; it was an Australian magic word, he afterwards told Richard, meaning Milk: immediately Elsie was comforted and came to sit on Charles’ knee and played with the buttons of his waistcoat for awhile until Charles sent her away.

“You have strange powers, Mr. Charles,” Richard said.

Charles answered: “I am fond of children, but the shout startled me; I am pleased that I did not do what, for a moment, I was tempted to do.”

“What was that?” asked Richard.

“I might have shouted myself,” said Charles.

“Why,” said Richard, “they would have liked that better. It would have been a great game for them. They probably expected it of you.”

“If I had shouted,” said Charles, “my shout would have either killed them outright or sent them mad. Probably it would have killed them, for they were standing close.”

Richard smiled a little foolishly. He did not know whether or not he was expected to laugh, for Charles spoke so gravely and carefully. So he said: “Indeed, what sort of shout would that be? Let me hear you shout.”

“It is not only children who would be hurt by my shout,” Charles said. “Men can be sent raving mad by it; the strongest, even, would be flung to the ground. It is a magic shout that I learned from the chief devil of the Northern Territory. I took eighteen years to perfect it, and yet I have used it, in all, no more than five times.”

Richard was so confused in his mind with the dream and the handkerchief and the word spoken to Elsie that he did not know what to say, so he muttered: “I’ll give you fifty pounds now to clear the cromlechs with a shout.”

“I see that you do not believe me,” Charles said. “Perhaps you have never before heard of the terror shout?”

Richard considered and said: “Well, I have read of the hero shout which the ancient Irish warriors used, that would drive armies backwards; and did not Hector, the Trojan, have a terrible shout? And there were sudden shouts in the woods of Greece. They were ascribed to the god Pan and would infect men with a madness of fear; from this legend indeed the word ‘panic’ has come into the English language. And I remember another shout in the Mabinogion, in the story of Lludd and Llevelys. It was a shriek that was heard on every May Eve and went through all hearts and so scared them that the men lost their hue and their strength and the women their senses, and the animals and trees, the earth and the waters were left barren. But it was caused by a dragon.”

“It must have been a British magician of the dragon clan,” said Charles. “I belonged to the Kangaroos. Yes, that tallies. The effect is not exactly given, but near enough.”

They reached the house at one o’clock, and Rachel was at the door, the dinner ready. “Rachel,” said Richard, ‘here is Mr. Charles to dinner; Mr. Charles is a great traveler.”

Rachel passed her hand over her eyes as if to dispel a cloud, but it may have been the sudden sunlight. Charles took her hand and kissed it, which surprised her. Rachel was graceful, small, with eyes unusually blue for the blackness of her hair, delicate in her movements, and with a voice rather low-pitched; she had a freakish sense of humor.

(“You would like Rachel,” said Crossley, “she visits me here sometimes.”)

Of Charles it would be difficult to say one thing or an-other: he was of middle age, and tall; his hair grey; his face never still for a moment; his eyes large and bright, sometimes yellow, sometimes brown, sometimes grey; his voice changed its tone and accent with the subject; his hands were brown and hairy at the back, his nails well cared for. Of Richard it is enough to say that he was a musician, not a strong man but a lucky one. Luck was his strength.

After dinner Charles and Richard washed the dishes together and Richard suddenly asked Charles if he would let him hear the shout: for he thought that he could not have peace of mind until he had heard it. So horrible a thing was, surely, worse to think about than to hear: for now he believed in the shout.

Charles stopped washing up; mop in hand. “As you wish,” said he, “but I have warned you what a shout it is. And if I shout it must be in a lonely place where nobody else can hear; and I shall not shout in the second degree, the degree which kills certainly, but in the first, which terrifies only, and when you want me to stop put your hands to your ears.”

“Agreed,” said Richard.

“I have never yet shouted to satisfy an idle curiosity,” said Charles, “but only when in danger of my life from enemies, black or white, and once when I was alone in the desert without food or drink. Then I was forced to shout, for food.”

Richard thought: “Well, at least I am a lucky man, and my luck will be good enough even for this.”

“I am not afraid,” he told Charles.

“We will walk out on the sand hills tomorrow early,” Charles said, “when nobody is stirring; and I will shout. You say you are not afraid.”

But Richard was very much afraid, and what made his fear worse was that somehow he could not talk to Rachel and tell her of it: he knew that if he told her she would either forbid him to go or she would come with him. If she forbade him to go, the fear of the shout and the sense of cowardice would hang over him ever afterwards; but if she came with him, either the shout would be nothing and she would have a new taunt for his credulity and Charles would laugh with her, or if it were something she might well be driven mad. So he said nothing.

Charles was invited to sleep at the cottage for the night, and they stayed up late talking,

Rachel told Richard when they were in bed that she liked Charles and that he certainly was a man who had seen many things, though a fool and a big baby. Then Rachel talked a great deal of nonsense, for she had had two glasses of wine which she seldom drank, and she said: “Oh, my dearest, I forgot to tell you. When I put on my buckled shoes this morning while you were away I found a buckle missing. I must have noticed that it was lost before I went to sleep last night and yet not fixed the loss firmly in my mind, so that it came out as a discovery in my dream; but I have a feeling, in fact I am sure that he is the man whom we met in our dream. But I don’t care, not I.”

Richard grew more and more afraid, and he dared not tell of the black silk handkerchief, or of Charles’ invitations to him to walk in the sand hills. And what was worse, Charles had used only a white handkerchief while he was in the house, so that he could not be sure whether he had seen it after all. Turning his head away, he said lamely: “Well, Charles knows a lot of things. I am going for a walk with him early tomorrow if you don’t mind; an early walk is what I need.”

“Oh, I’ll come too.” she said.

Richard could not think how to refuse her; he knew that he had made a mistake in telling her of the walk. But he said: “Charles will be very glad. At six o’clock then.”

At six o’clock he got up, but Rachel after the wine was too sleepy to come with them. She kissed him goodbye and off he went with Charles.

Richard had had a bad night. In his dreams nothing was in human terms, but confused and fearful, and he had felt himself more distant from Rachel than he had ever felt since their marriage, and the fear of the shout was gnawing at him. He was also hungry and cold. There was a stiff wind blowing towards the sea from the mountains and a few splashes of rain. Charles spoke hardly a word, but chewed a stalk of grass and walked fast.

Richard felt giddy, and said to Charles: “Wait a moment, I have a stitch in my side.” So they stopped, and Richard asked, gasping: “What sort of shout is it? Is it loud, or shrill? How is it produced? How can it madden a man?”

Charles was silent, so Richard went on with a foolish smile: “Sound, though, is a curious thing. I remember once, when I was at Cambridge, that a King’s College man had his turn of reading the evening lesson. He had not spoken ten words before there was a groaning and ringing and creaking, and pieces of wood and dust fell from the roof; for his voice was exactly attuned to that of the building, so that he had to stop, else the roof might have fallen; as you can break a wine glass, by playing its note on a violin.”

Charles consented to answer: “My shout is not a matter of tone or vibration but something not to be explained. It is a shout of pure evil, and there is no fixed place for it on the scale. It may take any note. It is pure terror, and if it were not for a certain intention of mine, which I need not tell you, I would not shout for you.”

Richard had a great gift of fear, and this new account of the shout disturbed him more and more; he wished himself at home in bed, and Charles two continents away. But he was fascinated. They were crossing the links now and going through the bent grass that pricked through his stockings and soaked them.

Now they were on the bare sand hills. From the highest of them Charles looked about him; he could see the beach stretched out for two miles and more. There was no one in sight. Then Richard saw Charles take something out of his pocket and begin carelessly to juggle it on his finger tip and spinning it up with finger and thumb to catch it on the back of his hand. It was Rachel’s buckle.

Richard’s breath came in gasps, his heart beat violently and he nearly vomited. He was shivering with cold, and yet sweating. Soon they came to an open place among the sand hills near the sea. There was a raised bank with sea holly growing on it and a little sickly grass; stones were strewn all around, brought there, it seemed, by the sea years before. Though the place was behind the first rampart of sand hills, there was a gap in the line through which a high tide might have broken, and the winds that continually swept through the gap kept them uncovered of sand. Richard had his hands in his trouser pockets for warmth and was nervously twisting a soft piece of wax around his right forefinger—a candle end that was in his pocket from the night before when he had gone downstairs to lock the door.

“Are you ready?” asked Charles.

Richard nodded.

A gull dipped over the crest of the sand hills and rose again screaming when it saw them. “Stand by the sea holly,” said Richard, with a dry mouth, “and I’ll be here among the stones, not too near. When I raise my hand, shout! When I put my fingers to my ears, stop at once.”

So Charles walked twenty steps toward the holly. Richard saw his broad back and the black silk handkerchief sticking from his pocket. He remembered the dream, and the shoe buckle and Elsie’s fear. His resolution broke: he hurriedly pulled the piece of wax in two, and sealed his ears. Charles did not see him.

He turned, and Richard gave the signal with his hand.

Charles leaned forward oddly, his chin thrust out, his teeth bared, and never before had Richard seen such a look of fear on a man’s face. He had not been prepared for that Charles’ face, that was usually soft and changing, uncertain as a cloud, now hardened to a rough stone mask, dead white at first, and then flushing outwards from the cheekbones red and redder, and at last as black, as if he were about to choke. His mouth then slowly opened to the full, and Richard fell on his face, his hands to his ears, in a faint.

When he came to himself he was lying alone among the stones. He sat up, wondering numbly whether he had been there long. He felt very weak and sick, with a chill on his heart that was worse than the chill of his body. He could not think. He put his hand down to lift himself up and it rested on a stone, a larger one than most of the others. He picked it up and felt its surface, absently. His mind wandered. He began to think about shoemaking, a trade of which he had known nothing, but now every trick was familiar to him. “I must be a shoemaker,” he said aloud.

Then he corrected himself: “No, I am a musician. Am I going mad?” He threw the stone from him; it struck against another and bounced off.

He asked himself: “Now why did I say that I was a shoemaker? It seemed a moment ago that I knew all there was to be known about shoemaking and now I know nothing at all about it. I must get home to Rachel. Why did I ever come out?”

Then he saw Charles on a sand hill a hundred yards away, gazing out to sea. He remembered his fear and made sure that the wax was in his ears: he stumbled to his feet. He saw a flurry on the sand and there was a rabbit lying on its side, twitching in a convulsion. As Richard moved towards it, the flurry ended: the rabbit was dead. Richard crept behind a sand hill out of Charles’ sight and then struck homeward, running awkwardly in the soft sand. He had not gone twenty paces before he came upon the gull. It was standing stupidly on the sand and did not rise at his approach, but fell over dead.

How Richard reached home he did not know, but there he was opening the back door and crawling upstairs on his hands and knees. He unsealed his ears.

Rachel was sitting up in bed, pale and trembling. “Thank God you’re back,” she said; “I have had a nightmare, the worst of all my life. It was frightful. I was in my dream, in the deepest dream of all, like the one of which I told you. I was like a stone, and I was aware of you near me; you were you, quite plain, though I was a stone, and you were in great fear and I could do nothing to help you, and you were waiting for something and the terrible thing did not happen to you, but it happened to me. I can’t tell you what it was, but it was as though all my nerves cried out in pain at once, and I was pierced through and through with a beam of some intense evil light and twisted inside out. I woke up and my heart was beating so fast that I had to gasp for breath. Do you think I had a heart attack and my heart missed a beat? They say it feels like that. Where have you been, dearest? Where is Mr. Charles?”

Richard sat on the bed and held her hand. “I have had a bad experience too,” he said. “I was out with Charles by the sea and as he went ahead to climb on the highest sand hill, I felt very faint and fell down among a patch of stones, and when I came to myself I was in a desperate sweat of fear and had to hurry home. So I came back running alone. It happened perhaps half an hour ago,” he said.

He did not tell her more. He asked, could he come back to bed and would she get breakfast? That was a thing she had not done all the years they were married.

“I am as ill as you,” said she. It was understood between them always that when Rachel was ill, Richard must be well.

“You are not.” said he, and fainted again.

She helped him to bed ungraciously and dressed herself and went slowly downstairs. A smell of coffee and bacon rose to meet her and there was Charles, who had lit the fire, putting two breakfasts on a tray. She was so relieved at not having to get breakfast and so confused by her experience that she thanked him and called him a darling, and he kissed her hand gravely and pressed it. He had made the breakfast exactly to her liking: the coffee was strong and the eggs fried on both sides.

Rachel fell in love with Charles. She had often fallen in love with men before and since her marriage, but it was her habit to tell Richard when this happened, as he agreed to tell her when it happened to him: so that the suffocation of passion was given a vent and there was no jealousy, for she used to say (and he had the liberty of saying): “Yes, I am in love with so-and-so, but I only love you.”

That was as far as it had ever gone. But this was different. Somehow, she did not know why, she could not own to being in love with Charles: for she no longer loved Richard. She hated him for being ill, and said that he was lazy, and a sham. So about noon he got up, but went groaning around the bedroom until she sent him back to bed to groan.

Charles helped her with the housework, doing all the cooking, but he did not go up to see Richard, since he had not been asked to do so. Rachel was ashamed, and apologized to Charles for Richard’s rudeness in running away from him. But Charles said mildly that he took it as no insult; he had felt queer himself that morning: it was as though something evil was astir in the air as they reached the sand hills. She told him that she too had had the same queer feeling.

Later she found all Lampton talking of it. The doctor maintained that it was an earth tremor, but the country people said that it had been the Devil passing by. He had come to fetch the black soul of Solomon Jones, the gamekeeper, found dead that morning in his cottage by the sand hills.

When Richard could go downstairs and walk about a little without groaning, Rachel sent him to the cobbler’s to get a new buckle for her shoe. She came with him to the bottom of the garden. The path ran beside a steep bank. Richard looked ill and groaned slightly as he walked, so Rachel, half in anger, half in fun, pushed him down the bank, where he fell sprawling among the nettles and old iron. Then she ran back into the house laughing loudly.

Richard sighed, tried to share the joke against himself with Rachel—but she had gone—heaved himself up, picked the shoes from among the nettles, and after awhile walked slowly up the bank, out of the gate, and down the lane in the unaccustomed glare of the sun.

When he reached the cobbler’s he sat down heavily. The cobbler was glad to talk to him. “You are looking bad,” said the cobbler.

Richard said: “Yes, on Friday morning I had a bit of a turn; I am only now recovering from it.”

“Good God,” burst out the cobbler, “if you had a bit of a turn, what did I not have? It was as if someone handled me raw, without my skin. It was as if someone seized my very soul and juggled with it, as you might juggle with a stone, and hurled me away. I shall never forget last Friday morning.”

A strange notion came to Richard that it was the cobbler’s soul which he had handled in the form of a stone. “It may be,” he thought, “that the souls of every man and woman and child in Lampton are lying there.” But he said nothing about this, asked for a buckle, and went home.

Rachel was ready with a kiss and a joke; he might have kept silent, for his silence always made Rachel ashamed. “But,” he thought, “why make her ashamed? From shame she goes to self-justification and picks a quarrel over something else and it’s ten times worse. I’ll be cheerful and accept the joke.”

He was unhappy. And Charles was established in the house: gentle-voiced, hard-working, and continually taking Richard’s part against Rachel’s scoffing. This was galling, because Rachel did not resent it.

(“The next part of the story,” said Crossley, “is that comic relief, an account of how Richard went again to the sand hills, to the heap of stones, and identified the souls of the doctor and rector—the doctor’s because it was shaped like a whiskey bottle and the rector’s because it was as black as original sin — and how he proved to himself that the notion was not fanciful. But I will skip that and come to the point where Rachel, two days later, suddenly became affectionate and loved Richard she said, more than ever before.”)

The reason was that Charles had gone away, nobody knows where, and had relaxed the buckle magic for the time, because he was confident that he could renew it on his return. So in a day or two Richard was well again and everything was as it had been, until one afternoon the door opened, and there stood Charles.

He entered without a word of greeting and hung his hat upon a peg. He sat down by the fire and asked: “When is supper ready?”

Richard looked at Rachel, his eyebrows raised, but Rachel seemed fascinated by the man.

She answered: “Eight o’clock,” in her low voice, and stooping down, drew off Charles’ muddy boots and found him a pair of Richard’s slippers.

Charles said: “Good. It is now seven o’clock. In another hour, supper. At nine o’clock the boy will bring the evening paper. At ten o’clock, Rachel, you and I sleep together.”

Richard thought that Charles must have gone suddenly mad. But Rachel answered quietly: “Why, of course, my dear.” Then she turned viciously to Richard: “And you run away, little man!” she said, and slapped his cheek with all her strength.

Richard stood puzzled, nursing his cheek. Since he could not believe that Rachel and Charles had both gone mad together, he must be mad himself. At all events, Rachel knew her mind, and they had a secret compact that if either of them ever wished to break the marriage promise, the other should not stand in the way. They had made this compact because they wished to feel themselves bound by love rather than by ceremony. So he said as calmly as he could: “Very well, Rachel. I shall leave you two together.”

Charles flung a boot at him, saying: “If you put your nose inside the door between now and breakfast time, I’ll shout the ears off your head.”

Richard went out this time not afraid, but cold inside and quite clear-headed. He went through the gate, down the lane, and across the links. It wanted three hours yet until sunset. He joked with the boys playing stump cricket on the school field. He skipped stones. He thought of Rachel and tears started to his eyes. Then he sang to comfort himself. “Oh, I’m certainly mad,” he said, “and what in the world has happened to my luck?”

At last he came to the stones. “Now,” he said, “I shall find my soul in this heap and I shall crack it into a hundred pieces with this hammer”—he had picked up the hammer in the coal shed as he came out.

Then he began looking for his soul. Now, one may recognize the soul of another man or woman, but one can never recognize one’s own. Richard could not find his. But by chance he came upon Rachel’s soul and recognized it (a slim green stone with glints of quartz in it) because she was estranged from him at the time. Against it lay another stone, an ugly misshapen flint of a mottled brown. He swore: “I’ll destroy this. It must be the soul of Charles.”

He kissed the soul of Rachel; it was like kissing her lips. Then he took the soul of Charles and poised his hammer. “I’ll knock you into fifty fragments!”

He paused. Richard had scruples. He knew that Rachel loved Charles better than himself, and he was bound to respect the compact. A third stone (his own, it must be) was lying the other side of Charles’ stone; it was of smooth grey granite, about the size of a cricket ball. He said to himself: “I will break my own soul in pieces and that will be the end of me.” The world grew black, his eyes ceased to focus, and he all but fainted. But he recovered himself, and with a great cry brought down the coal hammer, crack, and crack again, on the grey stone.

It split in four pieces, exuding a smell like gunpowder: and when Richard found that he was still alive and whole, he began to laugh and laugh. Oh, he was mad, quite mad! He flung the hammer away, lay down exhausted, and fell asleep.

He awoke as the sun was just setting. He went home in confusion, thinking: “This is a very bad dream and Rachel will help me out of it.”

When he came to the edge of the town he found a group of men talking excitedly under a lamp-post. One said: “About eight o’clock it happened, didn’t it?” The other said: “Yes.” A third said: “Ay, mad as a hatter. ‘Touch me,’ he says, ‘and I’ll shout I’ll shout you into a fit, the whole blasted police force of you. I’ll shout you mad.’ And the inspector says: ‘Now, Crossley, put your hands up, we’ve got you cornered at last.’ ‘One last chance,’ says he. ‘Go and leave me or I’ll shout you stiff and dead.’ ”

Richard had stopped to listen. “And what happened to Crossley then?” he said. “And what did the woman say?”

“‘For Christ’s sake,’ she said to the inspector, ‘go away or he’ll kill you.’”

“And did he shout?”

“He didn’t shout. He screwed up his face for a moment and drew in his breath. A’mighty, I’ve never seen such a ghastly looking face in my life. I had to take three or four brandies afterwards. And the inspector he drops the revolver and it goes off; but nobody hit. Then suddenly a change comes over this man Crossley. He claps his hands to his side and again to his heart, and his face goes smooth and dead again. Then he begins to laugh and dance and cut capers. And the woman stares and can’t believe her eyes and the police lead him off. If he was mad before, he was just harmless dotty now; and they had no trouble with him. He’s been taken off in the ambulance to the Royal West County Asylum.”

So Richard went home to Rachel and told her everything and she told him everything, though there was not much to tell. She had not fallen in love with Charles, she said; she was only teasing Richard and she had never said anything or heard Charles say anything in the least like what he told her; it was part of his dream. She loved him always and only him, for all his faults: which she went through—his stinginess, his talkativeness, his untidiness. Charles and she had eaten a quiet supper, and she did think it had been bad of Richard to rush off without a word of explanation and stay away for three hours like that. Charles might have murdered her. He did start pulling her about a bit, in fun, wanting her to dance with him, and then the knock came on the door, and the inspector shouted: “Walter Charles Crossley, in the name of the King, I arrest you for the murder of George Grant, Harry Grant, and Ada Coleman at Sydney, Australia.” Then Charles had gone absolutely mad. He had pulled out a shoe buckle and said to it: “Hold her for me.” And then he had told the police to go away or he’d shout them dead. After that he made a dreadful face at them and went to pieces altogether. “He was rather a nice man; I liked his face so much and feel so sorry for him.”

“Did you like that story?” asked Crossley.

“Yes,” said I, busy scoring, “a Milesian tale of the best Lucius Apuleius, I congratulate you.”

Crossley turned to me with a troubled face and hands clenched trembling. “Every word of it is true,” he said. “Crossley’s soul was cracked in four pieces and I’m a madman. Oh, I don’t blame Richard and Rachel. They are a pleasant, loving pair of fools and I’ve never wished them harm; they often visit me here. In any case, now that my soul lies broken in pieces, my powers are gone. Only one thing remains to me,” he said, “and that is the shout.”

I had been so busy scoring and listening to the story at the same time that I had not noticed the immense bank of black cloud that swam up until it spread across the sun and darkened the whole sky. Warm drops of rain fell: a flash of lightning dazzled us and with it came a smashing clap of thunder.

In a moment all was confusion. Down came a drenching rain, the cricketers dashed for cover, the lunatics began to scream, bellow, and fight. One tall young man, the same B. C. Brown who had once played for Hants, pulled all his clothes off and ran about stark naked. Outside the scoring box an old man with a beard began to pray to the thunder: “Bah! Bah! Bah!”

Crossley’s eyes twitched proudly. “Yes,” said he, pointing to the sky, “that’s the sort of shout it is; that’s the effect it has; but I can do better than that.” Then his face fell suddenly and became childishly unhappy and anxious. “O dear God,” he said, “he’ll shout at me again, Crossley will. He’ll freeze my marrow.”

The rain was rattling on the tin roof so that I could hardly hear him. Another flash, another clap of thunder even louder than the first. “But that’s only the second degree,” he shouted in my ear; “it’s the first that kills.”

“Oh,” he said. “Don’t you understand?” He smiled foolishly.

“I’m Richard now, and Crossley will kill me.”

The naked man was running about brandishing a cricket stump in either hand and screaming: an ugly sight. “Bah! Bah! Bah!” prayed the old man, the rain spouting down his back from his uptilted hat.

“Nonsense,” said I, “be a man, remember you’re Crossley. You’re a match for a dozen Richards. You played a game and lost, because Richard had the luck; but you still have the shout.”

I was feeling rather mad myself. Then the Asylum doctor rushed into the scoring box, his flannels streaming wet, still wearing pads and batting gloves, his glasses gone; he had heard our voices raised, and tore Crossley’s hands from mine. “To your dormitory at once, Crossley!” he ordered.

“I’ll not go,” said Crossley, proud again, “you miserable Snake and Apple Pie Man!”

The doctor seized him by his coat and tried to hustle him out.

Crossley flung him off, his eyes blazing with madness. “Get out,” he said, “and leave me alone here or I’ll shout. Do you hear? I’ll shout. I’ll kill the whole damn lot of you. I’ll shout the Asylum down. I’ll wither the grass. I’ll shout.” His face was distorted in terror. A red spot appeared on either cheek.

I put my fingers to my ears and ran out of the scoring box. I had run perhaps twenty yards, when an indescribable pang of fire spun me about and left me dazed and numbed. I escaped death somehow; I suppose that I am lucky, like the Richard of the story. But the lightning struck Crossley and the doctor dead.

Crossley’s body was found rigid; the doctor’s was crouched in a comer, his hands to his ears. Nobody could understand this because death had been instantaneous, and the doctor was not a man to stop his ears against thunder.

It makes a rather unsatisfactory end to the story to say that Rachel and Richard were the friends with whom I was staying—Crossley had described them most accurately—but that when I told them that a man called Charles Crossley had been struck at the same time as their friend the doctor, they seemed to take Crossley’s death casually by comparison with his. Richard looked blank; Rachel said: “Crossley? I think that was the man who called himself the Australian Illusionist and gave that wonderful conjuring show the other day. He had practically no apparatus but a black silk handkerchief. I liked his face so much. But Richard didn’t like it at all.”

“No, I couldn’t stand the way he looked at you all the time,” Richard said.

Host Commentary

“My story is true,” he said, “every word of it. Or, when I say that my story is ‘true,’ I mean at least that I am telling it in a new way. It is always the same story, but I sometimes vary the climax and even recast the characters. Variation keeps it fresh and therefore true. If I were always to use the same formula, it would soon drag and become false. I am interested in keeping it alive, and it is a true story, every word of it. I know the people in it personally. They are Lampton people.”

This is a story so choked with English iconography that it would be easy to overlook the racism at its core. There’s a bitter humour to that given this weird little island’s fondness for world domination but there’s also an insidious kind of horror it’s easy to miss the first time around and I did. The second time around though, it becomes all you can see.

Crossley is well-travelled, well-read, well-educated. He’s also the living embodiment of cultural appropriation in his usage of the shout. A white man who lives with the First Nations People, learns all he can from them and takes a powerful tool home with him for his own personal gain. No sense of recompense, no fair exchange, just a rich, well-educated Englishman showing up and stealing your things. If the shout was a real object, it would be next to the Elgin Marbles.

This element of the story is vital in the best and worst sense. The best because the arrogance that powers Crossley is what makes him such a compelling villain. The worst because that arrogance eclipses the culture he’s stolen from so completely. So much so that a review I read of the movie version of this story praises the director’s choice of ‘incorporating Australian Aboriginal mythology’. The offhand broad-brush dismissal of cultures other than our own is one of the express elevators to hell culture is littered with. Celebrity chef Jamie Oliver ran headlong into this last year when he released a children’s book featuring a First Nations protagonist and did exactly no research on how to respectfully and accurately present her culture. The story blew up, justifiably. He apologised. But if you’re looking for the truly insidious horror in this story, it’s that we’re a quarter of the way through the century after The Shout was published and cultural appropriation is still something that’s still regarded as ‘woke’.

What’s doubly ironic is that the story is shot through with horror that’s more than unsettling enough without this element. The movie version especially, currently on BFI Player where it’s got an introduction from the other Manx film critic Mark Kermode, is in direct conversation with the likes of Penda’s Fen which we discussed a couple of weeks ago. Both have that sense of tangible unease that so many UK folk horror stories of this time period embody. A sense of unease, it’s worth noting, that transcends that of the story itself. Graves’ formal language comes from his precisely structured poetic brain and his time, as do the story’s worst elements. This story is a nightmare, from the moment Crossley quietly introduces himself to the ending. This is the normal shattered by the impossible, and politely asking whether it wants another cup of tea. That’s the connective tissue with Penda’s Fen for me. Both are about characters marked as something different, but where Penda’s Fen uses sexual identity as both a springboard into and out of horror. The Shout uses courtesy and polite tea and scones bigotry. The instinct to not say anything when the man next to you says he can kill people with his voice. The offhand acceptance of the casual racism, incongruous and awful to us, but part of the story’s landscape. The end, where it implies, heavily that the two survivors have decided not to remember anything. Least said, soonest mended, my mum liked to say. She wasn’t always wrong. She was there.

That collision of the supernatural and the mundane embodies Hookland, the notional county of the UK perfectly too. So much so it put me in mind of The Hum, the noise emitted by electricity pylons in Hookland and the religion that worships them. The BBC have just released a drama series, The Listeners, based around the real life phenomenon of ‘The Hum’, and the moment I read that, the geography of where this story sits became clear to me. Hookland to its North, the blasted beach of M.R. James O Whistle and I’ll Come To You My Lad to the South. To the East, Penda’s Fen, to the west, Quatermass and further off the 28 Days Later movies. There’s even a hint of the story from a couple of weeks ago with the pragmatic approach taken to ‘Oh, well these stones are souls, I’ll just break this one.’ Systems of understanding, not our own, never talked about but always understood. Keep calm and be nice to the clever man, say hi to the fairies as you cross the Fairy Bridge and never, ever raise your voice unless you mean it. The polite illusion shattered and rebuilt. Least said, soonest mended. But for something to be mended it has to be broken and in the case of Crossley’s racism, acknowledged so we can understand why and how it was broken. The Shout is terrifying. How Crossley finds it, and uses it, is horrifying.

Amazingly well done. Thanks to all.

And PseudoPod wants to remind you, as Charles Crossley himself says: Every word of what I’m going to tell you is true. …

About the Author

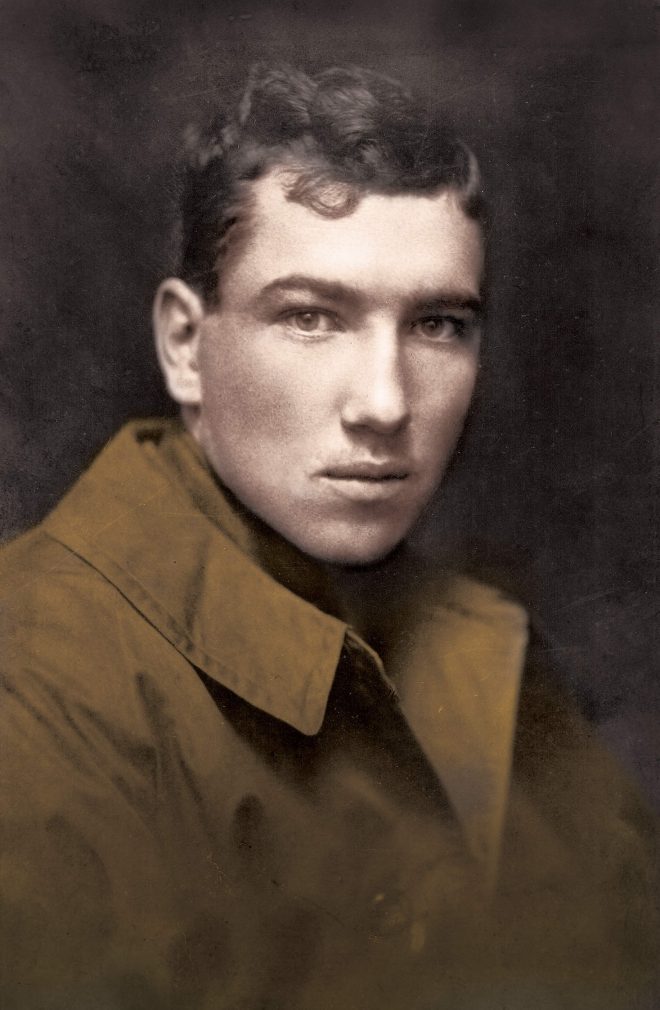

Robert Graves

Captain Robert von Ranke Graves was an English poet, soldier, historical novelist and critic. His father was Alfred Graves, a celebrated Irish poet and figure in the Gaelic revival; they were both Celticists and students of Irish mythology. Robert Graves produced more than 140 works in his lifetime: his poems, translations and innovative analysis of the Greek myths have never been out of print. He was also a renowned short story writer, with stories such as “The Tenement” still being popular today.

About the Narrator

Graeme Dunlop

Graeme has been involved with Escape Artists for many years, producing audio, hosting shows, narrating stories and keeping the websites going. He was born in Australia, although people have identified him as English, American and South African, amongst other nationalities.

He loves the spoken word and is lucky enough to have narrated for all the EA podcasts. Well, not CatsCast.

Graeme lives in Melbourne, Australia with his girl dog Zoë, a lovely and lively Husky mix.