PseudoPod 934: The Hollow Temple part two

The Hollow Temple (Part Two of The Dain Curse)

by Dashiel Hammett

IV

I spent most of the day fidgeting in and out of my room. The general vagueness of my job in this Temple hadn’t bothered me much before—I had had plenty of even more aimless operations in my twenty years of sleuthing—but now that Dr. Riese had found something to worry about—even though it was probably a medical worry and out of my field—I began to get restless, uneasy, irritable.

Dr. Riese did not show up that evening as he had promised. I supposed that one of the emergencies that are a regular part of a doctor’s life had held him elsewhere, but his not coming annoyed me.

I sat in my room from half past six on, with my door open, looking at Gabrielle Leggett’s door. Mildred took a tray into the girl’s room at a few minutes past seven. When she brought me mine I asked her how Gabrielle Leggett seemed to be.

“She’s all right, I suppose. I don’t think there’s much the matter with her but showing off.”

“What was she doing?”

“Sitting at the window, looking out, posing, if you ask me. How is it you’re not going down to the dining-room tonight?”

“Tired of eating in the graveyard atmosphere.”

At half-past seven Minnie Hershey left her mistress’ room, looking with startled eyes through my open door at me, but going on without saying anything. She returned at a little after eight, a few minutes before Mildred came up for my tray.

At nine o’clock Joseph appeared, spoke a few words about nothing in particular, smilingly refused the chair I offered him, and went into the girl’s room, opening the door without knocking. I cursed him and myself, because he had, for the time he was in my room, chased away my restlessness and uneasiness.

Half an hour later he left the girl’s room, nodded at me, said, “Good night,” and went down the corridor toward the rear. A couple of the house’s inmates passed my door between then and ten o’clock, apparently on their way to their rooms.

At a quarter to eleven Mildred appeared. I asked her not to close the door when she started to. She looked sharply at me, saying:

“I can’t stay, then.”

“If you knew what a bad humor I’m in you wouldn’t want to stay.”

She hesitated, lingering for a moment with her hand on the knob, bit her lip, and said:

“Oh, well, I’ll come back some time when you’re over your grouch,” and went away.

At eleven o’clock Minnie Hershey left the girl’s room again. I was tempted to stop her and try some questions on her, but didn’t. My last several attempts in that line had got me nothing, and I was in too disagreeable a mood for diplomacy. By this time I had given up all hope of seeing Dr. Riese before morning.

Turning off my lights, I sat in the dark, looking at the girl’s door and grumbling to myself, cursing the world. At a quarter to twelve Minnie Hershey, in hat and coat, as if she had come in from the street, went into the girl’s room once more. She remained inside until nearly one o’clock; and when she came out she closed the door very softly, walking tiptoe, an altogether unnecessary precaution on the thick carpet.

Because it was unnecessary it made me nervous. I went to my door and called softly:

“Minnie.”

She tiptoed on down the corridor as if she hadn’t heard me. That increased my jumpiness. I went after her, quickly, and stopped her by taking hold of one of her thin wrists.

Her Indian features were expressionless.

“How is she?”

“Miss Gabrielle’s all right, sir. You just leave her alone,” she mumbled.

“She’s not all right,” I growled, “and you know it. What’s she doing now?”

“Sleeping.”

“Doped?”

She raised angry dark eyes and let them drop again, saying nothing.

“She sent you out to get dope?” I demanded, tightening my grip on her wrist.

“She sent me out to get her some— some medicine, yes, sir.”

“And she took some and went to sleep?”

“Y-yes, sir.”

“We’re going back and have a look at her.”

The girl took a quick step away and tried to yank her wrist free. I held it.

“You leave me alone, Mister, or else I’ll yell.”

“I’ll leave you alone after we’ve had our look, maybe,” I said, turning her around with my other hand on her shoulder. “So if you’re going to yell, you might as well get started now.”

She wasn’t at all willing to go back, but she didn’t make me drag her.

Gabrielle Leggett’s door, like mine and all the guest-room doors, had no lock.

She was lying on her side in bed, sleeping quietly, the bed-clothes stirring gently with her breathing. Her small white face, at rest, with her curly brown hair tumbled over the little forehead, looked like a sick child’s.

I turned Minnie loose and went back to my room. Sitting there in the dark I understood why people bit their fingernails.

I sat there for an hour or more and then went for a cruise through the building, drawing the usual blank. In my dark room again, I took off my shoes, sat in the most comfortable chair, put my feet in another, hung a blanket over me, and went to sleep facing Gabrielle Leggett’s door, through my open doorway.

Later I opened my eyes for a moment, drowsily, decided that I had only dozed off for a moment, that it was too soon for another trip; closed my eyes, drifted back toward slumber, and then roused sluggishly again.

Something wasn’t right.

I wrestled my eyes open, then closed them. Whatever was wrong had to do with that. Blackness was before them when they were open, and when they were closed. That was reasonable enough, it was a dark, starless night, and my windows were out of the street lights’ range. That was reasonable enough—damned if it was!

My door was open, and the corridor lights burned all night. I opened my eyes again. No pale rectangle of light was in front of them, no dim shape of Gabrielle Leggett’s door.

I was too much awake now to jump up suddenly. I held my breath and listened, hearing nothing but the ticking of the watch on my wrist. Cautiously moving my hand, I looked at the luminous dial: 3:17. I had been asleep longer than I had thought—and the corridor light had been put out.

My head was numb, my whole body heavy, stiff, and there was a bad taste in my mouth. I got out from under my blanket, and out of my chairs, moving clumsily, my muscles stubborn, and crept on stocking feet to the door—bumped into the door. It had been closed. When I opened it, the corridor light was on as usual. The air coming through the door seemed surprisingly fresh, pure.

I turned, facing into my room, and sniffed. There was an odor of flowers, faint, a bit stuffy, more the odor of a closed place in which flowers had died than of flowers themselves. Lilies-of-the-valley, moon flowers, perhaps another one or two. I had a vague memory of having dreamed of a funeral. Trying to remember what I had dreamed, I leaned against the door-frame and nodded sleepily.

The jerking up of my neck muscles when my head had sunk too low awakened me. I wrestled my eyes open again, standing there on legs that didn’t seem part of me, stupidly wondering what it was all about and whether it wouldn’t be just as well to go to bed and sleep. While I drowsed over the thought I put out an arm against the wall, to take some of the strain off my tired legs. The hand—no more a part of me than the legs—touched the light button. I had enough sense to push it.

The light scorched my eyes. Squinting, I could once more see a world that was real to me, and I could remember that I had work to do. I made for the bathroom and doused my face and head in cold water. The water left me still stupid, muddled, but at least partly conscious.

Turning off my lights, I crossed to Gabrielle Leggett’s door, listened, and heard nothing. I opened the door quickly, stepped inside, and closed it.

My flashlight showed me an empty bed with covers thrown down across the foot. I put a hand on the hollow her body had made in the bed—cold. There was nobody in bathroom or dressing alcove. There were no signs of a fight. Under the edge of the bed lay a pair of slippers, and a green kimono, or something of the sort, was hung on the back of a chair. There was nothing to indicate that she had dressed before she left the room.

I went back to my own room for my shoes, and then walked down the front stairs to the ground floor, intending to go through the house from top to bottom, silently first. If I ran across nothing—as was probable—then I would start kicking in doors, turning people out of beds, and raising hell until I turned up the girl. I wanted to find her as soon as possible, but she had too long a start on me for a few minutes to make much difference. So if I didn’t waste any time getting down the stairs, neither did I run.

I was half-way between the second and first floor when I saw something move—or rather I saw the movement of something without seeing it. It moved from the direction of the street door toward the interior of the house. I was looking at the elevator door at the time, as I descended. The banister shut out my view of the street door. What I saw was a flash of movement through half a dozen of the spaces between the banister’s uprights. By the time I had brought my eyes into focus on it, there was nothing to see. I thought I had seen a face, but I knew that’s what anybody would have thought they had seen under the circumstances, and I knew that all I had actually seen was the movement of something pale.

The lobby, and what I could see of corridors, were vacant when I reached the ground floor. I moved in the direction that I imagined the moving thing I had seen must have taken—and stopped.

I heard—for the first time since I had awakened—a noise that I had not made. A shoe-sole had scuffed on the stone steps on the other side of the front door.

I walked to the front door, got one hand on the bolt, the other on the key, snapped them back together; and yanked the door open with my left hand, letting my right hand hang within a twist of my gun.

Eric Collinson stood on the top step.

“What the hell are you doing here?” I asked sourly.

It was a long story, and he was too excited to make it a clear one. As nearly as I could untangle his words, he had been in the habit of phoning Dr. Riese for daily reports on Gabrielle Leggett. Today—or rather yesterday—and last night he had been unable to get the doctor on the phone. He had called up as late as two o’clock this morning. Dr. Riese was not at home, he had been told, and none of his household knew where he was or why he was not at home. Collinson had immediately come to the neighborhood of the Temple, on the chance that he might see me, get some word of the girl. He hadn’t intended coming to the door—until he had seen me looking out.

“Until you did what?”

“Saw you.”

“When?”

“A minute ago, when you looked out.”

“You didn’t see me. What did you see?”

“Someone looking out—peeping out. I thought it was you.”

“You mean you hoped and persuaded yourself it was. It wasn’t. Who was it? What did he look like?”

“I don’t know. I thought it was you, and came up from the corner where I was sitting in the car. Is Gabrielle all right?”

“Sure.” There was no use telling him I was hunting for her, and have him blow up on me. “Don’t talk so loud. Riese’s people don’t know where he is?”

“No, and they seem worried. But that’s all right if Gabrielle is all right.” His haggard young face became pleading. “Could—could I see her? Just for a second? I won’t say anything. She needn’t know I’m here. Can’t you arrange it somehow, please?”

This bird was young, tall, broad, strong, and perfectly willing to have himself broken all up for Gabrielle Leggett’s sake. I knew something was wrong, but I didn’t know what; neither did I know what I was going to have to do to make it right, how much help I was going to need. I couldn’t afford to turn him away; on the other hand I couldn’t give him the low down on the racket; that would have turned him into a wild man.

“Come in. I’m on one of my inspection tours. You can go along if you keep quiet and behave, and afterwards we’ll see what we can do.”

He came in acting and looking as if I had been St. Peter letting him into Heaven.

I closed the door and led him through the lobby, down the main corridor. So far as I could tell, we had the joint to ourselves.

And then we didn’t.

V

Around a corner just ahead of us came Gabrielle Leggett, barefooted and in a yellow silk nightgown that was splashed with dark stains.

In both hands, held out in front of her as she walked, she carried a large dagger, almost a small sword. It was red and wet. Her hands and bare forearms were red and wet. There was a dab of blood on one of her cheeks. Her eyes were clear, bright, calm. Her small forehead was smooth, her mouth and chin firmly set.

She walked up to me, her untroubled gaze holding my troubled one, thrust the dagger toward me, and said evenly, just as if she had expected to find me there, had come there to see me:

“Take it. It is evidence. I killed him.”

“Huh?”

Still looking straight into my eyes, she said:

“You are a detective. Take me to where they will hang me.”

It was easier to move my hand than my tongue. I took the bloody dagger from her. It was a broad, thick-bladed weapon, double-edged, with a bronze hilt like a cross.

Eric Collinson thrust himself past me, babbling words that nobody could have made out, going for the girl with shaking outstretched hands.

She shrank over against the wall, away from him, fear in her face.

“Don’t let him touch me,” she begged.

“Gabrielle!” he cried, reaching for her.

“No! No!” she gasped.

I walked into his arms, my body between him and her, facing him, pressing him back with a hand on his chest, growling at him:

“Be still, you.”

He put his big lean hands on my shoulders and began pushing me out of the way. I got ready to rap him on the chin with the dagger hilt. Looking past me at the girl, he seemed to forget his intention of forcing me out of his road. I leaned on the hand that was against his chest, moving him back until the wall stopped him.

“Be still till we see what’s happened,” I ordered.

His hands had gone loose on my shoulders. I stepped back from him, and a little to one side, so that I could see both him and her, facing each other from opposite walls.

“What’s happened?” I asked, pointing the dagger at the girl.

She had recovered her calmness.

“Come. I’ll show you. Don’t let Eric come, please.”

“He won’t bother you,” I promised.

She nodded at that, gravely, and led the way back down the corridor, around the corner, and to the little iron door that opened into the place where the altar was. The door was standing open. She went first through the door. I followed her, Collinson me. It was dark there under a dark sky. Walking unhurriedly on bare feet that must have found the marble floor chilly, she led us straight toward the altar, a vague dark shape without its tarpaulin.

I got my flashlight out as we walked. When she halted in front of the altar and said, “There,” I clicked on the light.

On the first of the three altar steps, Dr. Riese lay dead on his back.

His face was composed, as if he were sleeping. His arms straight down at his sides. His clothes were not rumpled, though his coat and vest were unbuttoned in front. His shirt front was all blood. There were four holes in his shirt front, all alike, all the shape and size that the weapon the girl had given me would have made.

No blood was coming from his wounds now, but when I put a hand on his head I found it not quite cold. There was blood on the altar steps, and on the floor below, where his nose glasses, unbroken, on the end of their black ribbon, lay.

I straightened up and swung the beam of my flashlight directly into the girl’s face. She blinked and squinted in the light, but her face showed nothing except that physical discomfort.

“You killed him?”

Young Collinson came out of his trance to bawl:

“No!”

“Shut up,” I snarled at him, stepping closer to the girl, so he couldn’t wedge himself in between us. “Did you?” I asked her again.

“Are you surprised?” she asked quietly. “You were present when my step-mother told of the curse of the Dain blood in me, of how I had murdered my mother before I was five, of my warped mind, of the blackness that would be in my life and in the lives of all that I touched. Is this,” she pointed almost carelessly at the dead man, “anything that should not be expected by those who come in contact with me?”

“Don’t talk nonsense,” I said while I tried to figure out her calmness. I knew she was a hophead, had seen her coked to the ears before, but this wasn’t that. I didn’t know what it was. “Why did you kill him?”

Collinson grabbed my near arm and yanked me around to face him. He was all on fire.

“We can’t stand here talking,” he exclaimed. “We’ve got to get her out of here, away from here. We’ve got to hide the body, or put it some place where they’ll think somebody else did it. You know how those things are done. I’ll take her home. You fix it.”

He had nice ideas.

“Yeah? What’ll I do? Frame it on one of the Filipino boys, so they’ll hang him instead of her?”

“Yes, that’s it. You know how to—”

“Like hell that’s it. Not with me.”

His face got redder. He stammered:

“I—I didn’t mean so they’ll hang anybody, really. I wouldn’t want you to do that. But couldn’t it be fixed for him to get away? I—I’d make it worth his while—any amount. He could—”

“Turn it off,” I growled. “You’re talking out of my territory.”

“But you’ve got to,” he insisted. “You came here to see that nothing happened to Gabrielle, and you’ve got to go through with this.”

“Yeah? You’re full of funny ideas, son.”

“I know it’s a lot to ask, but I’ll pay you—”

“Stop it. You’ve wasted enough time for us.” I took my arm out of his hands and turned to the girl, again, asking: “Who else was here when it happened?”

“No one.”

I played my light around the place again, even up the walls, on corpse and altar, and discovered nothing I hadn’t already seen. I put the dagger beside the body, snapped off the light, and told Collinson:

“We’ll take Miss Leggett up to her room.”

“For God’s sake, let’s get her out of this house now, while there’s time,” he urged.

I said she would look swell running through the streets in bare feet, with nothing on but a blood-spattered nightie.

He jerked his arms out of his overcoat, saying, “I’ve got the car just down the street; I can carry her to it,” and started toward her with the coat held out.

She ran around to the other side of me, moaning:

“Oh, don’t let him touch me!”

I put out an arm to stop this. It wasn’t strong enough. The girl got behind me. Collinson pursued her and she came around in front. I felt like the center of a merry-go-round, and didn’t like the feel of it.

When Collinson appeared in front again, I drove my shoulder into his side, sending him staggering over against the side of the altar. Following him, I planted myself in front of the big sap and blew off steam:

“Let her alone. Let me alone. The next break you make, I’m going to sock your jaw with the flat of a gun. If you want it now, say so.”

He got his legs straight under him and began:

“But, good God, you can’t—”

I had heard enough of that. I cut in with:

“Stop it. If you want to play with us you’ve got to stop bellyaching, do what you’re told, and let her alone. Yes or no?”

He muttered: “All right.”

I turned around and saw the girl—a gray shadow running toward the open iron door, her bare feet making little noise on the marble floor. My shoes seemed to make an ungodly racket as I went after her.

Just inside the door I. caught her with an arm around her waist. The next moment my arm was jerked away, and I was flung aside, crashing into the wall, slipping down to one knee.

Collinson, looking eight feet tall in the darkness, stood close to me, storming down at me, but all I could pick out of his many words was a “damn you.”

I was in a swell frame of mind when I got up from my knee. It took all my twenty years of the-job-comes-first training to keep my hand off my gun. Bending his face with it would have been sweet.

“There’s one coming to you, boy,” I promised him, “but it’ll wait. We can’t spend the whole morning clowning here.”

I don’t know what his reply was; he mumbled it to my back while I was going over to where the girl was watching us from the doorway.

“We’ll go up to your room,” I told her.

“Not Eric,” she objected.

“He won’t bother you,” I promised again. “Go ahead.”

She hesitated, and then went through the doorway. Collinson looking partly sheepish, partly savage, and altogether dissatisfied, followed me through. I closed the door, asking the girl if she had the key.

She said no, as if she hadn’t known there was one.

We rode up to the fifth floor in the elevator, the girl keeping me always between her and her fiancée. He stared fixedly at nothing. I studied the girl’s face, still trying to dope her out, to decide whether she had been shocked into sanity or deeper into insanity. Looking at her, the first guess seemed most likely, but I had a hunch that it wasn’t. At that, I thought sourly, she’s no goofier than her boyfriend, the big simpleton.

We saw nobody in the corridor between the elevator and her room. I switched on her lights and we went in; I closed the door and put my back to it.

Collinson put his overcoat and hat on a chair and stood beside them, folding his arms. The girl sat on the side of her bed, looking at my feet.

“Tell us the whole thing, quick,” I commanded her.

She raised her eyes and said:

“I should like to go to sleep now.”

That settled the question of her sanity so far as I was concerned: she hadn’t any at all. But now I had another thing to worry about. This room was not exactly as it had been before. Something had been changed since I had been in it not many minutes ago. I shut my eyes, trying to shake up my memory for a picture of it as it had been then; I opened them, looking at it as it was now.

“Can’t I?” she asked.

I let her wait for a reply while I put my gaze around the room, checking it up item by item, as far as I could. The only change I could put my finger on was Collinson’s coat and hat on the chair. There was no mystery to their being there, and the chair, I decided, was what had bothered me. It still did. I went to it and picked up the coat. There was nothing under it. Then I knew what was wrong; a green kimono, or something of the sort, had been there, and was not there now. I didn’t see it elsewhere in the room, and I didn’t have enough confidence in its being there to make a complete search.

I wondered what its absence meant while I told the girl:

“Not now. Go in the bathroom, wash the blood off your hands and arms, and get dressed for the street. Take the clothes in there with you. When you come out, give your nightgown to Collinson.” I turned to him: “Put it in your pocket and keep it there. Don’t go out of this room and don’t let anybody come in. I won’t be gone long. Got a gun?”

“No, but I—”

The girl got up from the bed, came over to stand close to me, and interrupted him:

“You cannot leave him here with me. I won’t have it. Isn’t it enough for you that I have killed one man tonight? Don’t make me murder another.” She spoke earnestly, but without great excitement, almost as if she were declining an invitation that someone was pressing on her.

“I’ve got to go out for a while, and you can’t stay alone. Do what I tell you.”

“You don’t realize what you’re doing,” she protested in a thin, tired voice. “You know there’s a curse on me, and on all who touch me. You know what happened to Dr. Riese, whose only crime was that he was my physician.” Her back was to Eric Collinson. She lifted her face so that I could see rather than hear the nearly soundless words on her lips shaped: “I love Eric. Let him go.”

I felt sweat in my armpits. A little more of this and she would have had me ready for the cell next to hers: I was actually tempted to let her have her way. I jerked my thumb at the bathroom and said:

“You can stay in there, if you like, but he’ll have to stay here.”

She nodded her small, suddenly hopeless, face once, gently, and went into the dressing alcove. When she crossed from there to the bathroom, carrying some clothes in her hands, a tear was shiny below each eye.

I gave my gun to Collinson. The brown hand in which he took it was tense and shaky. He was making a lot of noise with his breathing. I told him:

“She’s trying to save you from the family curse. She says she loves you. Now don’t be a sap. Give me some help this once instead of trouble.”

He tried to say something, couldn’t, grabbed my nearest hand, did his best to disable it. I took it away from him, and went down to the scene of Dr. Riese’s murder.

I had some difficulty in getting there. The iron door through which we had passed a few minutes ago was locked now. I went around to the other one. It too was locked. The lock seemed simple enough. I went at it with the fancy attachments on my pocket knife, and presently had it open.

I didn’t find the green kimono inside. Dr. Riese’s body was gone from the altar steps, was nowhere in sight. The dagger was gone, and every trace of blood—except where the pool on the marble floor had left a yellow stain—had been mopped up.

Somebody had been tidying up.

I put my flashlight back in my pocket and headed for an alcove off the lobby, where I had seen a telephone. The phone was there, but it was dead. I put it down and set out for Minnie Hershey’s room on the sixth floor. I hadn’t been able to do much with her, but I knew she was devoted to Gabrielle Leggett, and perhaps I could send her out to do my phoning.

I opened her door—lockless as the others—and went in, closing the door behind me. Holding one hand over the front of my flashlight, I snapped it on. Enough light leaked out to show me the mulatto girl in her bed, sleeping. The windows were closed, the atmosphere heavy, with a faint odor that was familiar—the odor of a closed place where flowers had died, the odor I had smelled in my own room earlier in the night.

I looked at the girl again. She was lying on her back, breathing through open mouth, her face more an Indian’s than ever with the peace of heavy sleep on it. Looking at her, I felt drowsy myself. It seemed a shame to rouse her. Perhaps she was dreaming of—

I shook my head, trying to clear it of the muddle settling there. Lilies-of-the-valley, moonflowers . . . that had died . . . death was restful . . . so was sleep . . . little death, somebody called it . . . it was restful . . . sleep . . . sleep . . . the flashlight was heavy in my hand . . . too heavy . . . hell with it . . . I let it drop . . . it fell on my foot . . . puzzling me . . . who touched my foot? somebody . . . Gabrielle Leggett . . . asking to be saved . . . Gabrielle Leggett . . . a job . . . Gabrielle Leggett . . . the job comes first . . . work to do . . .

I tried to shake my head again, tried desperately. It weighed a ton, and would barely creep from side to side. I felt myself swaying, put out a foot to steady myself. The foot and leg were weak, limp, dough. I had to take another step or fall; took it; forced my head up, my eyes open, to find a place to fall, and saw the window six inches ahead of me.

I swayed forward until the window sill caught my thighs, steadying me. My hands rested on the sill. I tried to find the handles on the bottom of the window, wasn’t sure whether I had them or not, put everything I had into an attempt to raise the window.

It didn’t budge.

I think I sobbed then, and holding the sill with my right hand, I beat the glass out of the center of the pane with my open left.

Air that stung like ammonia came through the opening. I put my face to it, hanging to the sill with both hands, sucking it in through mouth, nose, eyes, ears, and pores; laughing, with water from my eyes trickling down into my mouth.

I hung there drinking air only until I was reasonably sure of my legs under me again, and of my eyesight; until I was able to think and move again, though neither speedily nor surely. I couldn’t afford to wait longer. I put a handkerchief over my face and nose and turned away from the window.

Not more than three feet away, there in the black room, a pale bright thing like a body, but not like flesh, stood writhing before me.

Host Commentary

Splash:

Pseudopod, episode 934 for August 16th, 2024. The Hollow Temple, part 2, by Dashiell Hammett.

Host:

I’m Josh Tuttle, Associate Editor at Pseudopod, your host for this week. And as of two weeks ago, I’m officially Visiting Assistant Professor of Spooky Literature. Classes start a week from Monday. Wish me luck.

Publication History:

“The Hollow Temple” was originally published in Black Mask, December 1928. If you missed part one, go back an episode, where you’ll learn more. If you want to hear about the process of locating copies of these ancient literary artifacts for the Public Domain Showcase, hang around for my office hours after the show.

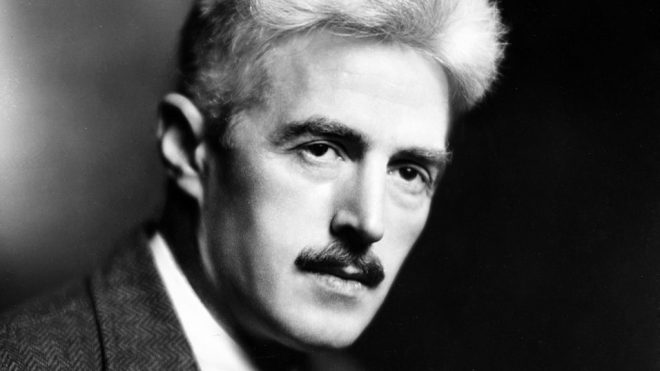

Author Bio:

In the meantime, Dashiell Hammett remains a deceased American writer of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories. As Alex noted last episode, among the characters he created are Sam Spade (The Maltese Falcon), Nick and Nora Charles (The Thin Man), The Continental Op (Red Harvest and The Dain Curse), and the comic strip character Secret Agent X-9. His obituary in the New York Times described him as “the dean of the … ‘hard boiled’ school of detective fiction.” See the notes to Part 1 to learn more about him.

Narrator Bio:

Now, it’s the absolute worst when the cast changes between installments. We don’t do that here. We’re sticking with Dave Robison (ph. Robbisun), who remains an avid Literary and Sonic Alchemist who pursues a wide range of creative explorations. A Brainstormer, Keeper of the Buttery Man-Voice (patent still pending), Pattern Seeker, Dream Weaver, and Eternal Optimist, Dave’s efforts to boost the awesomeness of the world can be found at The Roundtable Podcast, the Vex Mosaic e-zine, and through his creative studio, Wonderthing Studios. Dave is the creator of ARCHIVOS, an online story development and presentation app, as well as the curator of the Palaethos Patreon feed where he explores a fantasy mega-city one street at a time.

Audio Production this week is courtesy of Chelsea Davis.

Transition:

And now, without further ado, get ready for part two. The cult wouldn’t lie to you, folks, so everything you’re about to hear, and we promise, is true.

Outro:

Each year for the Public Domain Showcase we read dozens of stories before choosing four or five. The process works pretty much like our ordinary reading period. The stories go in the hopper, usually, hilariously, with Shawn or Alex as the submitting author, so we get to reject Shawn and Alex; and we read, comment, vote, meet, and ultimately accept and reject. What’s different about the Public Domain Showcase is that before we can do any of this, we have to find a copy of the story. Shawn has seemingly spent his whole life compiling word documents of these stories, just waiting for Congress to stop extending Copyright. But he doesn’t have everything. That’s where I come in.

My special skill is tracking down copies of obscure texts that may only exist in one copy.

And yes, before you ask, I have held a copy of the Necronomicon. It’s in the Eberly Family Special Collections Library at Penn State, call number BF1999.A6335 1977. (It’s a reprint, of course.) I won’t speculate why the circulating copy is listed as “Unavailable.”

When we open the Showcase reading period, Shawn sends us all a list of the stories under consideration. Inevitably, two or three items on the list indicate he couldn’t locate a copy. Sometimes I can locate a copy within an hour or a day. Here’s how it goes if it’s easy: I fill out an Interlibrary Loan request form, and a librarian basically does all of this work for me. Seriously, librarians are the unsung heroes of our shared literary world. Thank one next chance you get! They’re very helpful if you’re friendly, which is important when you’re in my line of work and you might cold call a dozen people you don’t know to ask them if they’d be willing to go to the annex and pull a box for you “just in case something uncatalogued might be in it.”

Sometimes finding the story takes months, like it did for “The Isle of Blue Men” last year—episode 847, if you’re curious. In that case, after exhausting literally every academic resource at my disposal, including writing individually to every single library listed in WorldCat as having even a single issue of Ghost Stories (and striking out), I registered for and attended the annual conference of the Research Society of American Periodicals. I basically just asked if anyone knew anyone who had a copy of the issue of Ghost Stories I needed. I was lucky: one collector had attended purely for the purpose of making his archive available to researchers. But, alas, he did not have it. He did, however, have a friend who might, and he promised to ask his friend about it “the next time he was in his area.” I figured that would probably be that, but less than a week later, he wrote back to me with a scanned copy of what I was looking for.

“The Hollow Temple” was not nearly as involved as that, but it still took some work—I got it in about a week of looking. I had to write to the UCLA Library Special Collections librarians. A wonderfully helpful woman named Julie located the story, agreed to scan it for me even though it was delicate. And I mean delicate—the color scans show little pieces of the cover that fell apart and appear on the scanner glass on subsequent pages. But I had the story, and it was glorious.

And now you have it too. I hope you enjoyed it. If you’re a Patreon subscriber, we encourage you to pop over to our Discord channel and tell us. I’ll leave you with an earnest plea: If you or anyone you know has copies of any old pulp magazines, don’t let them get thrown out. If you don’t want them or the responsibility of preserving them, find a library that will take them. UCLA is a really good candidate, but not the only one. If you don’t know who to give them to, write to me at Joshua@escapeartists.net, and I’ll help you make the connection.

Now, the cult might not lie to you, but I did, at least about having only one plea. I’m also going to ask you for money. Escape Artists is an organization that’s deeply important to me. I’ve been listening to Pseudopod since 2012, and, like Wikipedia, we always ask you to be the super-user who supports what we do. The fact is, like Wikipedia, we need the money or we can’t do the work. It’s that simple. Head to pseudopod.org and feed the pod if you can. Remember that sharing an episode with a friend helps us too. I started the Spooky Society as a monthly literary club where we sat around in the dark and listened to Pseudopod. Do your part and carry the sickly taper forward.

Closing:

PseudoPod is part of the Escape Artists Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, and is distributed under a creative commons, attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives license. Download and listen all you like, but don’t change or sell it. Theme music is by permission of Anders Manga.

Office hours are closed, everyone, but until next time, Pseudopod knows that “not all birds are people.”

About the Author

Dashiell Hammett

Dashiell Hammett was an American writer of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories. He was also a screenwriter and political activist. Among the characters he created are Sam Spade (The Maltese Falcon), Nick and Nora Charles (The Thin Man), The Continental Op (Red Harvest and The Dain Curse) and the comic strip character Secret Agent X-9.

In his obituary in The New York Times, he was described as “the dean of the… ‘hard-boiled’ school of detective fiction.” Time included Hammett’s 1929 novel Red Harvest on its list of the 100 best English-language novels published between 1923 and 2005. In 1990, the Crime Writers’ Association picked three of his five novels for their list of The Top 100 Crime Novels of All Time. Five years later, The Maltese Falcon placed second on The Top 100 Mystery Novels of All Time as selected by the Mystery Writers of America; Red Harvest, The Glass Key and The Thin Man were also on the list. His novels and stories also had a significant influence on films, including the genres of private eye/detective fiction, mystery thrillers, and film noir.

About the Narrator

Dave Robison

Dave Robison is an avid Literary and Sonic Alchemist who pursues a wide range of creative explorations. A Brainstormer, Keeper of the Buttery Man-Voice (patent pending), Pattern Seeker, Dream Weaver, and Eternal Optimist, Dave’s efforts to boost the awesomeness of the world can be found at The Roundtable Podcast, the Vex Mosaic e-zine, and through his creative studio, Wonderthing Studios. Dave is the creator of ARCHIVOS, an online story development and presentation app, as well as the curator of the Palaethos Patreon feed where he explores a fantasy mega-city one street at a time.