PseudoPod 933: The Hollow Temple part one

The Hollow Temple (Part Two of The Dain Curse)

by Dashiel Hammett

I

Eric Collison came into my office. There was too much pink in his eyes and not any in his skin. He sat down and said:

“She can’t go. They can’t let her go. You’ve got to go with her.”

His voice, like his face, was dull and tired and hopeless and bewildered.

“Miss Leggett?” I asked, though I didn’t need to; and then: “How is she now?”

“You’ve killed her.”

He spoke bitterly, but without heat, not looking at me; staring at my inkwell, with a beaten look in his eyes.

I ignored the accusation, saying:

“Where is it that she can’t go, and that I’ve got to go with her?”

He replied, still staring at the inkwell, that Madison Andrews was crazy, and so was Dr. Riese, and so would he—Collinson—be if this thing kept on.

“I thought they were just about as cool and level-headed a pair as you could find.”

“But good God! They want to let her go to this Joseph.”

“Who is he?”

Instead of answering my question he began complaining that it was all my fault; that if it hadn’t been for me, her father and step-mother would still be alive, Gabrielle would know nothing of their “horrible past,” nothing of the crime that she herself had committed as the five-year-old tool of her step-mother, and, most important of all, she would not have been made believe that she was accursed—bound to live in blackness herself and to bring blackness into the lives of all who came in contact with her.

“She’s better off now than she’s ever been,” I argued. “I know that, in the shape she was in when it all broke, she was upset a lot by the melodramatic curse her step-mother put on her, or said was on her. But I can’t see that she’s as bad off as when she was under her step-mother’s influence.”

He lifted his haggard young face to look at me, and he spoke as if his throat hurt him:

“I’m going to tell you: I didn’t think anybody could be as brutal as you were to her.”

“Is that,” I asked irritably, “why you’re here now telling me I’ve got to go somewhere with her?”

“But what else can I do?” he demanded, puckering his brows, his lower lip drooping down from his teeth. “They’re going to let her go. They’re crazy, I tell you. And she can’t go alone like that—with only Minnie.”

“Go with her yourself. You think you—”

“But I can’t.” Face, voice, and the slant of his wide shoulders were advertisements of hopelessness. “Good God! Don’t you think I would? But she won’t even let me see her. She’s afraid of the curse settling on me. I—I haven’t seen her for a week. She wouldn’t let me. You’ve got to go. There’s nobody else that’s—”

“That’s brutal enough?” I suggested.

“You know her, and you know the whole story, and you’re already in it. You can take care of her.” He took hold of my wrist with a big sunburned hand and pushed his face over the desk toward me. “You’ve got to go. And you’ve got to see that nothing happens to her.”

I took my wrist out of his hand and growled:

“I haven’t got to do anything. I’m not likely to do anything that I know as little about as I do about this. What is it? Where is she going?”

“I told you,” he said wearily. “She’s going to Joseph’s. They’re going to let her go. It’s Dr. Riese’s doing, though Andrews ought to know better. They’re crazy. You’ve got to—”

“Who is Joseph?”

“That’s it. Who is he? What do they know about him? Or about what will happen to Gaby in his Temple? For a man like Andrews to agree to such a thing!”

He put his elbows on my desk, his face between his hands, and stared at the desk-top with dull bloodshot eyes.

“How long since you’ve slept?”

“Tuesday,” he muttered without looking up, “or maybe Sunday. What difference does it make? You’ll go with her?”

“I don’t know. Maybe you think you’ve given me the whole story, but you haven’t. You haven’t told me anything. Try again? Start with Joseph.”

“Another cult,” he said impatiently. “He calls his place the Temple of the Holy Grail. I don’t know where Gabrielle ran into them, but she’s known them for a month or so. I suppose it’s the fashionable cult just now. You know how they come and go in California. This Joseph came to see her after her trouble, and now she wants to go to the Temple and stay for a while. They do that—retreats—like the Catholics.

“Dr. Riese—God knows why—said he thought it would be good for her. Andrews said, ‘No,’ at first, but they persuaded him. He said he had had the cult investigated and it seemed all right. I suppose he meant by that that there was no proof that anybody had ever been murdered there. It’s idiotic! What if Mrs. Payson Laurence and Mrs. Ralph Coleman are members? Their social positions won’t keep them from being made fools of like anybody else. And Mrs. Livingston Rodman’s being a resident of the Temple now doesn’t have to mean anything except that she too can be deceived. But Andrews seems to think that because the cult’s dupes are beyond suspicion, so must it be. So the old ass has agreed to let Gabrielle go there.

“I don’t want her to go, but what can I do? She won’t even see me. But I’m damned if she’s going there with nobody but her maid, even if Dr. Riese will see her every day. There’s got to be somebody there to see that nothing happens to her. You’ve got to go. I meant what I said about your being brutal, but I know—I know you—she will be safe with you there. You will go, won’t you?”

I thought it over without enthusiasm. It wasn’t my idea of an inviting job, but the Continental Detective Agency was in business to make money, and I couldn’t very well turn down any honest and profitable employment in our line.

Collinson took his face from between his hands and said:

“I don’t know what else you may have on hand, but—the money end of it—any amount you charge for your services will be quite all right.”

“Andrews is in charge of the girl’s affairs,” I stalled. “I’ll have to see him first.”

Collinson said eagerly that that was all right. He had spoken to both Andrews and Riese about engaging me, and they had not only consented, but thought it an excellent idea. Collinson used my telephone to call Andrews and tell him I would be over at his office in a few minutes.

Collinson didn’t go to the lawyer’s office with me. He said gloomily that if he did he would get into another argument with Andrews, and after a solid week of trying to change the old man’s mind he had given it up as a futile business. Leaving me, Collinson gripped my hand violently, asking me to promise all sorts of things concerning the carefulness with which I would guard Gabrielle Leggett. I advised him to get some sleep.

Madison Andrews was a tall, gaunt man of sixty, with ragged white hair, eyebrows and mustache that exaggerated the ruddiness of his face—a bony, hard-muscled face. He wore his clothes loose, chewed tobacco, and had twice in the past ten years been named correspondent in divorce suits.

“I dare say,” he told me, “young Collinson has babbled all sorts of nonsense to you. He seems to think I’m in my second childhood—as good as told me so.”

“He doesn’t think you ought to let her go.”

“He has spared no pains in making that known to me,” the lawyer said. “But even though he is her fiancé, I am responsible for her care; and I prefer to follow Dr. Riese’s advice in this. He is her physician. He insists that letting her go to the Temple for a week or two of seclusion from the world will do more to restore her sanity than anything else that can be done. Can I disregard that?

“Joseph may be—probably is—a charlatan, but he certainly is the only person to whom Gabrielle has willingly talked, and in whose company she has been at peace, since her parents’ deaths. Dr. Riese tells me that to cross her in her desire to go to the Temple will be to send her mind deeper into its illness. Am I to snap my fingers at Riese’s opinion because young Collinson doesn’t like it?”

I said: “No.”

“I have learned something of the members of this sect. I know decent, responsible, even prominent people, who are members. Mrs. Livingston Rodman is living there now. I have no illusions concerning the sect: it is probably as full of quackery as any other. But I am not interested in it as religion—rather as therapeutics—as a cure for Gabrielle’s mental illness vouched for by her physician. The character of the cult’s membership is such that I will consider Gabrielle safe there. Even if I were not quite sure of that, I still should think that no other consideration should be allowed to interfere with her recovery. That, as I see it, comes first.”

I nodded my agreement and asked:

“When is she proposing to go?”

“Tomorrow morning. You can go then?”

“Yeah. What is the layout?”

“I’ll notify Joseph that you are coming. You are supposed to be a male nurse, and will be given a room close to Gabrielle’s. They know of her mental trouble, so your presence there will be quite all right, whether they believe you to be a nurse or not. You needn’t go with her. Perhaps it would be best if you were there when she arrives, at, say, eleven o’clock. There is no need of my giving you instructions. It is simply a matter of taking every precaution, seeing that nothing happens to her. Dr. Riese and I have every confidence in your ability to handle it. Gabrielle’s maid, Minnie, will be with her, and Dr. Riese will call every day. Ask for Aaronia Haldorn when you arrive. She is Joseph’s wife, I think, and manages the material end of the cult.”

“Does Gabrielle Leggett know I’m going?”

“No,” Andrews said, “and I don’t think we need say anything to her about it. You’ll make your watch over her as unobtrusive as possible, of course, and, while she knows you, I don’t think that, in her present condition, she will pay enough attention to your presence to resent it. If she does—well, we’ll see.”

II

From the street, the following morning, the Temple of the Holy Grail looked like what it had originally been—a six-story yellow brick apartment building. There was nothing about its exterior to show that it wasn’t one still. I rang the doorbell.

The door was opened immediately by a broad-shouldered meaty woman of some year close to fifty. She was a good three inches taller than my five feet six. Flesh hung in little bags on her face, but there was neither softness nor looseness in eyes and mouth. Her long upper lip had been shaved. She was dressed in black.

I told her I wanted to see Mrs. Haldorn. She took me into a small, dimly lighted reception room to one side of the lobby, told me to wait there—her voice was a heavy bass—and went away.

I put my gladstone bag on a chair, my hat on top of it, and sat down. Drawn blinds let in too little light for me to make out much of the room, but the carpet was soft and thick and what I could see of the furniture leaned more toward luxury than severity.

No sound came from anywhere in the building. I looked at the open doorway and discovered that I was being looked over. A small boy of twelve or thirteen stood there staring at me with big dark eyes that seemed to have lights of their own in the semi-darkness. I said:

“Hello, son.”

The boy said nothing, looked at me a minute longer with the cold, unblinking, embarrassing stare that only children can manage, turned his back on me, and walked away, making no more noise than he had made coming.

Looks like I’m going to have a swell time here, I thought, if the two I’ve seen are fair samples of the joint’s occupants—besides Gabrielle Leggett, who’s still worse.

A woman, walking silently on the thick carpet, appeared in the doorway, came through it. She was tall, graceful, and her dark eyes had lights of their own, like the boy’s. That’s all I could see then.

I stood up and asked:

“Mrs. Haldorn?”

“Yes.” Her voice, saying that one word, was the most beautiful I had ever heard. It wasn’t a voice, it was pure music.

“Madison Andrews told you I was coming?” I said, hoping she would speak more than one syllable this time.

“Oh, you are Miss Leggett’s attendant?” The slightest of pauses before the last word told me that she didn’t believe in the male nurse pretext.

Her voice was all that the first Yes had made me think it. “Yes, he told me.”

She walked past me to raise a blind, letting in a fat rectangle of morning sun. While I blinked at her in the sudden brightness, she sat down and motioned me back to my chair.

I saw her eyes first. They were enormous, black, soft, glowing, heavily fringed with black lashes. They were the only live, human, things in her face. There was warmth and there was beauty in her oval, olive-skinned face; but, except for the eyes, it was unnatural—almost weird—warmth and beauty. It was as if her face were not a face, but a mask that she had worn until it had almost become a face. Even the curving red mouth looked not so much like flesh as like an almost perfect imitation of flesh—softer, redder, maybe warmer, than genuine flesh, but not genuine. Above this face—or mask—uncut black hair was bound close to her head, parted in the middle, drawn down across temples and upper ears to meet in a knot on the nape of her neck. Her neck was long, strong, slender; her body tall, fully fleshed, supple; her clothes dark, silky, part of her body.

She offered me Russian cigarettes in a white jade case. I apologized for sticking to my Fatimas, and struck a match on the smoking stand she pushed out between us.

When our cigarettes were burning she said:

“We shall try to make you as comfortable as possible. We are neither barbarians nor fanatics. I explain this because so many people are surprised to find us neither. This is a Temple, but none of us supposes that happiness, comfort, or any of the ordinary matters of civilized living, will desecrate it. You are not one of us. Perhaps—I hope—you will become one of us. However—do not squirm—you won’t, I assure you, be annoyed. You may attend our services or not, as you choose, and you may come and go as you wish. You will show us, I am sure, the same consideration we show you, and I am equally sure that you will not interfere in any way with anything you see—no matter how peculiar you may think it—unless it definitely and disagreeably affects your—ah—patient, Miss Leggett.”

“Of course not,” I promised.

She smiled, as if to thank me, rubbed her cigarette’s end into the ash tray, and stood up, saying;

“I’ll show you your room.”

Picking up my hat and bag, I followed her out into the lobby, where we entered an automatic elevator. She took me to a room on the fifth floor. Everything in the room, as in the connecting bathroom, was white: white papered walls and painted ceiling; white enameled chairs, bed, table, dresser, fixtures and woodwork; white felt on the floor. None of the furniture was hospital furniture, but the solid whiteness of everything gave it that appearance. There were two windows in the bedroom, looking out over roofs, and one in the bathroom. The only doors were those connecting bathroom and bedroom, bedroom and corridor. Neither had a lock.

I left my hat and bag there and went with the woman to see the room Gabrielle Leggett would occupy. Its door faced mine across a six-foot corridor’s purple carpet. The interior was a duplicate of my room’s, except that, on the opposite side from the bathroom, there was a small square dressing-room without windows.

“Her maid?”

“She will sleep in one of the servant’s rooms on the top floor. Shall we go downstairs now?”

She took me down to the second floor and pushed back half of a pair of sliding doors, showing me a room dark with walnut paneling and furniture.

“Our dining-room,” she said, as she slid the door shut again and moved on along the corridor. “Breakfast and luncheon are usually served in our rooms, but for dinner—at seven—you may either come here or have it in your room, as you prefer. This is the library.”

We were at the doorway of a large square room where tan burlaped walls ran up high behind glass-fronted bookcases.

A man turned from one of the cases toward us. He was a tall man, built like a statue, in a black silk robe. His thick hair, rather long, and his thick beard, trimmed round, were white and glossy.

Aaronia Haldorn introduced me to him, calling him Joseph. He came forward to give me a white and even-toothed smile and a warm strong hand. His face was healthily pink and without line or wrinkle. It was a tranquil face, especially the clear brown eyes, somehow making you feel at peace with the world. The same soothing quality was in his baritone voice as he said:

“We are happy to have you here.”

The words were merely polite, meaningless; yet, as he said them, I believed that for some reason he was happy. I understood now Gabrielle Leggett’s desire to come to this place. I said that I, too, was happy to be there, and at the time I actually thought I was.

We went on, the woman showing me various other rooms, and finally leading me to a small iron door on the ground floor. She opened it and said:

“Our services are held here.”

The floor was of white marble, pentagonal titles. The walls were white, smooth, unbroken except for this door and another exactly like it on the other side. These four straight, whitewashed, undecorated walls rose straight up for six stories—to the sky. There was no ceiling, no roof. In the other end of the room—of what had been a room until it had been cut through to the sky—a gray tarpaulin covered something that was shaped like an upright piano, but several times larger than any piano.

“The altar,” Aaronia Haldorn explained.

Behind us a soft buzzing sounded. “That is probably Miss Leggett,” the woman said, and we went back through the iron door.

At the elevator I left her, going up to my room. Presently I heard the rustle of people moving in the corridor, going into Gabrielle Leggett’s room. I didn’t hear her voice, but I did hear Minnie Hershey, her mulatto maid, answering some question Aaronia Haldorn had asked, and I heard the bass rumble of the woman who had let me into the house.

A few minutes later a small frosted globe fixed to the white telephone on my bedside table glowed, and I was asked what I wanted for luncheon. “Anything and coffee will do,” I said, and agreed that cold sliced meat and artichoke salad sounded appetizing, declined dessert, and then went into the bathroom to wash.

A maid in black and white brought the meal in to me on a white tray. She was somewhere in her middle twenties, a hearty, pink and plump blonde, with blue eyes that looked curiously at me and had jokes in them.

I said something about the food on the tray looking, good. She said, “Oh, yes, sir,” without seriousness, put the tray on the table, looked at me out of the corners of twinkling eyes, and went out.

After I had eaten I dug a bottle of King George scotch out of my bag, put it on the table beside the tray, and went into conference with it and a deck of cigarettes. Sounds drifted up through the open windows, but none came from inside the building until, an hour or so later, the blonde maid returned for the tray.

She pretended she didn’t see the bottle. I asked:

“Can I be shot at sunrise for having that here?”

She put up her tawny eyebrows and said:

“I really can’t say,” gathering up the tray.

“Ever use it yourself?”

“What?” The skin around her eyes twitched. “A shot at sunrise?”

“Yeah. Or now.”

She carried the tray toward the door, smiling, saying:

“I couldn’t—now. The Village Blacksmith would break my neck if she smelled it on me.”

The Village Blacksmith, I guessed, was the big woman with the bass voice.

“Later? When you’re through for the day?”

She said, “Maybe,” over her plump shoulder as she went through the door.

I spent the afternoon in my room. Dr. Riese came in to see me a little before five o’clock, after visiting Gabrielle Leggett’s room. He was a gray-faced, slender, dandified man with a crisp, precise way of turning out his words, usually emphasizing them by making gestures with the black-ribboned nose-glasses that I had never seen on his nose. I had learned that I stood high in his estimation because I had discovered that Edgar Leggett had been murdered, immediately after he—Riese—had pronounced him a suicide.

He told me the girl was in a better frame of mind than she had been since her parents’ deaths, and cautioned me against making my surveillance of her too thorough.

“The less she is reminded that she is being guarded, the better for her. I am glad you are here, but, after all, it is not likely that you will find anything to do.”

I promised to manage things so that the girl would see as little of me as possible, and the doctor went away, saying he would be in again in the morning.

I went down to the dining-room for dinner. There were eight of us at the table: Mrs. Livingston Rodman, a tall, frail woman with transparent skin, faded, tired eyes, and a voice that never rose above a semi-whisper; a man named Fleming, who was young, dark, very thin, with a dark mustache and the detached air of one who had a lot of things on his mind; a Miss Hillen, sharp of chin and voice, scrawny, forty, with an eager, intense manner; a Mrs. Pavlow, who was quite young, with a high-cheek-boned dark face and dark eyes that avoided everybody’s gaze; Aaronia Haldorn; and her son, Manuel, the boy who had looked at me from the reception room doorway. Neither Joseph nor Gabrielle Leggett appeared.

The food, served by two Filipino boys, was good. There was little conversation—except that which Miss Hillen made—and none of it religious. She tried to prod Fleming into conversation with questions about Aztec customs. He replied evasively, busy with his own thoughts. Getting nothing from him, Miss Hillen turned to Manuel Haldorn, asking him what he intended being when he grew up, a question any boy hears often enough to be bored by. He smiled at her with a shyness that didn’t seem sincere to me—remembering the stare he had given me—and replied that he didn’t know—whatever Mama decided was best—and turned his eyes to his plate again.

Miss Hillen’s gaze switched to Mrs. Pavlow, whose face suddenly went panicky with embarrassment. Aaronia Haldorn saved her from the sharp-chinned woman’s curiosity by asking:

“How are your roses, Miss Hillen?” Miss Hillen talked roses through dessert and coffee.

Ill

At nine o’clock I got hold of Gabrielle Leggett’s maid—Minnie Hershey—as she was leaving her mistress’ room. The mulatto girl’s eyes jerked wide when she saw me standing in the doorway of my room.

“Come in. Didn’t Dr. Riese tell you I was here?”

“No, sir. Are—are you—You’re not wanting anything with Miss Gabrielle, sir?”

“Just looking out for her, to see that nothing happens. So you and I are really working together. And if you’ll keep me wised up, let me know everything she does and says, and what others do and say, and so on, you’ll be helping me, and helping her, because then I won’t have to bother her.”

The girl said, “Yes, sir,” readily enough; but, so far as I could make out from examining her dark face, my cooperative idea wasn’t getting over any too well.

“How is she this evening?”

“She’s right cheerful this evening, sir. She likes this place.”

“How did she spend the afternoon and evening?”

“She—I don’t know, sir. She just kind of spent it—quiet like.”

No news there. I said:

“Dr. Riese thinks she’ll be better off not knowing I’m here, so don’t say anything about me to her.”

“No, sir, I sure won’t,” she promised but it sounded more polite than sincere.

At ten-thirty the plump blonde maid who had brought up my luncheon came in to have some scotch and some cigarettes with me. She insisted that we would have to be very quiet, so the Village Blacksmith wouldn’t learn that she was there; but I wasn’t a lot impressed by her insistence; I knew that as likely as not the girl had been sent up to me.

Her name was Mildred. She was careless, pleasant, a bit tough, and shrewd without being intelligent. She told me she had been working in the establishment for six months, since the present Temple had been opened. It had been donated to the cult by Mrs. Rodman. Mildred’s attitude toward her employers’ religion was one of tolerant indifference. They were decent enough people, she said. There were no wild parties of the sort that got other cults into the newspapers; and she supposed they had as good a religion as any, but she herself was a Methodist, and that was good enough for her.

She told me that there were half a dozen converts staying there in addition to the ones I had seen at dinner; and that at times there had been as many as twenty or twenty-five of them, all, she added, “real society people.” When she asked me what I was doing there, I told her the truth, except that I didn’t mention my detective agency connection.

“Is she really cracked?” she asked.

“No, but she’s too close to it to be left alone. You’ve seen her before?”

“She’s been here for services, but this is the first time she has even stayed.”

“Here often?”

“I’ve seen her twice.”

“See her today?”

“I took her dinner in, but I didn’t get a good look at her. It was nearly dark, the lights weren’t on, and she was lying on the bed.”

Mildred went off at eleven-thirty. A few minutes later I crossed the corridor to put my ear against Gabrielle Leggett’s door, keeping it there until my neck got tired—and that’s all the good it did me.

I returned to my room, smoked a cigarette, put a flashlight in my pocket, and went for a stroll through the building. The thick carpets that were everywhere made silent walking easy. Lights burned dimly in the corridors. I wandered around for nearly an hour, seeing nobody, hearing breathing through a few bedroom doors, but nothing else. I didn’t do any prying, but confined myself to the corridors and more public rooms, like dining-room, library, reception rooms and so on. The iron doors leading to the hollow core of the building where services were held were locked. I tried both of them.

Ten minutes more of listening at the girl’s door brought me nothing. I went to bed. At four-something I got up again, put on slippers and bathrobe, and went for another stroll. It was no more profitable than the first.

Dr. Riese visited my room at ten the next morning, apparently quite pleased with the progress his patient was making.

I caught Minnie Hershey in the corridor a little later, tried to get some information out of her, and got nothing but a lot of polite Yes, sirs.

When Mildred brought my luncheon in at noon she told me that services would be held at nine o’clock that evening.

In the library, after luncheon, I found Fleming busy making notes from a stack of books. He didn’t seem to feel like talking, so I wandered out. The Village Blacksmith passed me in the corridor, paying no attention to me until I spoke, then barely nodding. Aaronia Haldorn came to my room later that afternoon to smoke a cigarette and ask if anything could be done to make me more comfortable. Joseph was in Gabrielle Leggett’s room for an hour. I could hear his voice, but, no matter how tight I clamped my ear to her door, I couldn’t catch his words.

Before dinner I went out for half an hour’s walk in the streets, stocking up with cigarettes, magazines and newspapers.

The shy Mrs. Pavlow didn’t appear for dinner. Neither did Gabrielle Leggett, but Joseph was there, and a man and woman I had not seen before. He was a well-tailored, carefully mannered man, stout, bald, and sallow, a Major Jeffries. The woman was his wife, a pleasant sort of person in spite of a kittenish way that was thirty years too young for her.

Joseph, at the head of the table, eating no more than half a dozen good bites, speaking not many more than that number of words, seemed to have the same sort of soothing effect on everyone as he had on me. Even the sharp-chinned Hillen woman prodded nobody with questions. Presently, however, I discovered that there was one at the table who seemed to have escaped this influence—the boy Manuel. I caught him—once, and only for a split second—glancing at his father almost furtively through long lashes; and what I saw in the boy’s eyes was either contempt or hatred. I had only his eyes to go by; his face remained angelic. It was only a quick flash that I got of the eyes, but one of those things was in them. I watched the boy surreptitiously through the rest of the meal, but he never looked at Joseph again. He looked often at his mother—somewhat furtively too—but when his eyes were on her there was adoration in them.

I attended the services in the Temple’s hollow core that night. The altar, uncovered by tarpaulin now, was a glistening, dazzling, affair of white and crystal in a beam of blue-white light that slanted down from an edge of the roof. The beam was so strong that the altar seemed to quiver in it, to expand and contract. The glare hurt my eyes, tired them, but held them. When I wanted to look around at the congregation I had to fight with my eyes to get them away from the altar.

There were between thirty and forty people there, sitting on white enameled benches. Only ten of them, including me, were men. Men and women sat stiffly on their benches, staring at the dazzling altar with peculiarly fixed, unblinking gazes. Faces seemed white and unreal in the reflected glare, pupils of wide eyes were shrunken.

I saw Gabrielle Leggett on the other side of the room, but she was sitting in the front row, and I couldn’t see her face. Minnie Hershey was beside her.

Joseph, in a white robe, moved to and fro in front of the altar, going through some ritual, I didn’t know enough about religious ceremony to tell how this one differed from others. It was rather impressive, in a very dignified way. The strained, rigid, attention of the people on the benches gave a tense, expectant, air to it all, as if something tremendous, or violent, or exciting, was about to happen. Nothing of the sort did happen. There was some chanting in which everybody took part. The whole thing lasted an hour and ten minutes.

The congregation went out slowly, not talking much, most of them looking tired and worn, as if they had been through some sort of emotional struggle. I, who knew nothing about whatever spiritual significance the service may have had, felt somewhat the same way myself, probably from staring so long at the dazzling white altar.

I went slowly toward one of the little iron doors, waiting for a closer look at Gabrielle Leggett. Close to the door she passed me, not looking at me. She was thinner than when I had last seen her—ten days before—and what had been barely a suggestion of hollowness around her eyes and in her cheeks then was now a pronounced hollowness. Her small mouth was drawn tight, the lips colorless. She was no paler than usual, because she had always been white-cheeked, but now her whiteness seemed less healthy. Her green-brown eyes were more brown than green, enlarged, blank. She walked as in her sleep, with Minnie beside her.

I tried to catch the mulatto’s eyes, but she too was walking blank-faced and dazed.

Those of the congregation who were not staying in the building went away. The others vanished into their rooms. Mildred came into my room for more drinks and smokes. I got no information out of her, nor she out of me.

The house quieted for the night. I left my bed three times at odd hours to prowl through the building. I saw nothing, heard nothing, that was meat to my grinder.

The next day Dr. Riese reported still further improvement in his patient. I wondered what sort of shape she had been in before—if she was better now, as I had seen her last night. I laid in wait for Minnie in the corridor. Her face was not yet clear of last night’s daze. I could get nothing out of her.

I had a brief conversation with the boy Manuel that day. I strolled into the library and found him snuggled into a big chair, reading a book entitled Candide.

“Morning. What’s exciting in your young life today?”

“Morning,” he replied calmly. “What’s your opinion of Mildred now? Rather nice legs—hasn’t she?—if you like them a bit fat.”

I laughed at that one and asked: “What do you know about it—a young sprout of your age?”

He stared at me coldly for a moment and then returned his big-eyed gaze to the book. Fleming came into the room. I exchanged Good morning’s with him and went away.

Three more days went by.

On each of them Dr. Riese expressed increasing satisfaction with Gabrielle Leggett’s condition. I saw her four or five times in those three days and she didn’t look any better to me, but I wasn’t a doctor. I gave up trying to get anything out of Minnie. She had gone into a trance; the last time I tried to question her I had to call her three times before she even heard me. I spoke to Dr. Riese about her, but he didn’t think it was important.

“Probably just the worry and strain of nursing her mistress. You know how devoted she is to Miss Leggett.”

I said that didn’t sound like an explanation to me.

I continued to roam the corridors at night, profitlessly, chiefly because that was about the only thing I could do to earn my pay. New faces came and went. I attended services again—a carbon copy of the first ceremony.

Occasionally I saw and exchanged a few words with Aaronia Haldorn and Joseph. He spent a lot of time with Gabrielle Leggett. Once I asked for his opinion of her condition. He said something about her passing through a spiritual crisis. I felt reassured by his words at the time, but, later, away from him, I thought them over and found that they really hadn’t meant anything at all—not anything I could understand.

The plump blonde Mildred came in every evening for an hour or so. We had both given up trying to pump the other, it was now simply a sociable hour or two over whiskey and cigarettes. I went down to the Agency one afternoon. There were nine telephone messages and a letter from Eric Collinson on my desk—all demanding assurance that all was well with Gabrielle Leggett. I phoned him that it was.

On the fourth morning, Dr. Riese seemed less sure that the girl was improving; and by the next day he was noticeably worried, though I couldn’t get any details out of him. He told me he would be in again to see her at seven that evening.

Host Commentary

PseudoPod, Episode 933 for August 11th. 2024 – “The Hollow Temple” by Dashiell Hammett (Part 1 of 3).

Happy 18th birthday, PseudoPod! 18 years ago today we started this wild journey with Scott Sigler’s “Bag Man.” It feels wild being part of a podcast that is old enough to vote. We thought there was little better way to celebrate this milestone than with a three-part episode from one of America’s foundational writers. My father-in-law, Barry, has loved reading the works of Dashiell Hammett, so I wanted to dedicate this story to him. Happy PseudoPod’s Birthday, Pops.

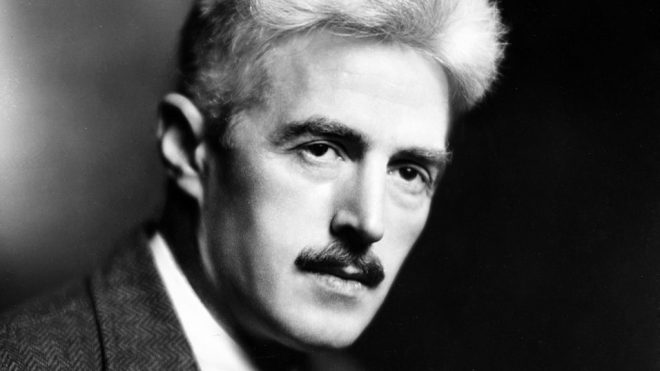

Dashiell Hammett was an American writer of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories. Among the characters he created are Sam Spade (The Maltese Falcon), Nick and Nora Charles (The Thin Man), The Continental Op (Red Harvest and The Dain Curse) and the comic strip character Secret Agent X-9.

In his obituary in The New York Times, he was described as “the dean of the… ‘hard-boiled’ school of detective fiction.” Time included Hammett’s 1929 novel Red Harvest on its list of the 100 best English-language novels published between 1923 and 2005. In 1990, the Crime Writers’ Association picked three of his five novels for their list of The Top 100 Crime Novels of All Time. Five years later, The Maltese Falcon placed second on The Top 100 Mystery Novels of All Time as selected by the Mystery Writers of America; Red Harvest, The Glass Key and The Thin Man were also on the list. His novels and stories also had a significant influence on films, including the genres of private eye/detective fiction, mystery thrillers, and film noir.

So how did Mr. Hammett wander into PseudoPod Towers? That, like many things, is entirely the fault of Grady Hendrix. Grady’s been hanging out here since episode 76. He’s been plotting and waiting for sixteen years to see this part of his sinister plan bear fruit. Mild spoilers if you want to skip ahead thirty or so seconds, but I assure you, the spoilers didn’t prevent me from reading this story and subjecting my horror book club to it. Spoilers are also part of Grady’s diabolical plan. He planted a seed at StokerCon just mentioning on an offhand way, “Have y’all read Dashiell Hammett? Did you know he wrote a novel that fits in the horror genre? It has Arthurian Cults, Human Sacrifice, and Ghost Punching. Completely bonkers! You have to read it.” So we did. You may be concerned that this first of three episodes may not fully pay off the promise, but let not your hearts be troubled. Grady is watching you. Watching OUT for you.

“The Hollow Temple” was first published in Black Mask, December 1928. This is the second of four novelettes from the magazine of detective, adventure, and western stories that were later fixed up into the novel The Dain Curse.

Since we started discussing whether to run this story, there was only ever one narrator under consideration. Dave Robison is an avid Literary and Sonic Alchemist who pursues a wide range of creative explorations. A Brainstormer, Keeper of the Buttery Man-Voice (patent pending), Pattern Seeker, Dream Weaver, and Eternal Optimist, Dave’s efforts to boost the awesomeness of the world can be found at The Roundtable Podcast, the Vex Mosaic e-zine, and through his creative studio, Wonderthing Studios. Dave is the creator of ARCHIVOS, an online story development and presentation app, as well as the curator of the Palaethos Patreon feed where he explores a fantasy mega-city one street at a time. Audio Production this week is courtesy of Chelsea Davis.

Now, read up on your grail legends to ensure you can pick the proper one from a lineup, and check yourself into the temple. The character of the cult’s membership is such that we will consider you safe there. We promise you, it’s true.

Like much of the work of this era, it is reflective of the times, and Hammett worked to ensure the authenticity of the voice. It is worth noting that not all of his female characters are shrinking violets. His Black characters often show a mistrust of cops and private detectives that still have that smell of authority, but with a slightly different moral code. And his characters will refuse to pin crimes on foreign servants even though it would be convenient and easy. It’s interesting to look into this world critically and both how far and how little progress we’ve made. For some perspective, Hammett was elected president of the Civil Rights Congress in 1946, and was later imprisoned for contempt of court after refusing to turn over a donor list for a bail fund. After that he refused to cooperate with McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee and got blacklisted and his books went out of print. We’re glad to do our part to help preserve and promote a part of our literary history.

Now on to form. The fix-up novel is an odd beast, but it’s been around for as long as there’s been an appetite for cheap novels. This can range from a serialized story to assembling a bunch of related short stories, draping a frame around them, and selling it as a new package. Dickens is an example of the first, and In Search of the Unknown by Robert W. Chambers, Nights of the Round Table by Margery Lawrence, and the Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury fall into the second. The name “fix-up” comes from the changes that the author needs to make in the original texts, to make them fit together as though they were a novel. Foreshadowing of events from the later stories may be jammed into an early chapter of the fix-up, and character development may be interleaved throughout the book. Contradictions and inconsistencies between episodes are usually worked out. This form really exploded when mass-market paperbacks hit the spinner racks and were distributed to troops during World War 2. And again with the paperback booms of the late 70s and 80s.

The Dain Curse is an interesting fix-up. Usually the interstitial pieces are gently folded in, but Hammett made a lot of stylistic adjustments between the magazine and the novel. For simplicity, we had originally thought to pull the text from the relevant sections of the novels. However, we do our due diligence for preservation and accuracy of what has and has not entered the public domain. Associate Editor Josh Tuttle worked his research magic and located a copy of December 1928’s Black Mask, and while the story is essentially the same, there so many subtle differences, almost as if Hammett rewrote the whole novel from memory. Both are great fun. Hammett’s straightforward style drags you along effortlessly and makes the pages fly. The novel should enter the public domain in 2025, but there’s no reason to wait if you don’t want to. That said, we’ve got two more installments coming up for you on the next two Fridays if you’re feeling patient. And Dave’s narration is worth it.

Make sure to swing over to PseudoPod.org to check out the art Josh Tuttle acquired from Black Mask. We’re using it as the header for these episodes. While you’re there, click on feed the pod to donate and subscribe, because everything we do is funded by you.

Pseudopod is part of Escape Artists incorporated and is distributed under a creative commons attribution non-commercial no derivatives 4.0 international license. Theme music is by permission of Anders Manga.

PseudoPod knows that the outcome of successful planning always looks like luck to saps.

About the Author

Dashiell Hammett

Dashiell Hammett was an American writer of hard-boiled detective novels and short stories. He was also a screenwriter and political activist. Among the characters he created are Sam Spade (The Maltese Falcon), Nick and Nora Charles (The Thin Man), The Continental Op (Red Harvest and The Dain Curse) and the comic strip character Secret Agent X-9.

In his obituary in The New York Times, he was described as “the dean of the… ‘hard-boiled’ school of detective fiction.” Time included Hammett’s 1929 novel Red Harvest on its list of the 100 best English-language novels published between 1923 and 2005. In 1990, the Crime Writers’ Association picked three of his five novels for their list of The Top 100 Crime Novels of All Time. Five years later, The Maltese Falcon placed second on The Top 100 Mystery Novels of All Time as selected by the Mystery Writers of America; Red Harvest, The Glass Key and The Thin Man were also on the list. His novels and stories also had a significant influence on films, including the genres of private eye/detective fiction, mystery thrillers, and film noir.

About the Narrator

Dave Robison

Dave Robison is an avid Literary and Sonic Alchemist who pursues a wide range of creative explorations. A Brainstormer, Keeper of the Buttery Man-Voice (patent pending), Pattern Seeker, Dream Weaver, and Eternal Optimist, Dave’s efforts to boost the awesomeness of the world can be found at The Roundtable Podcast, the Vex Mosaic e-zine, and through his creative studio, Wonderthing Studios. Dave is the creator of ARCHIVOS, an online story development and presentation app, as well as the curator of the Palaethos Patreon feed where he explores a fantasy mega-city one street at a time.