PseudoPod 930: The Dabblers

The Dabblers

by W.F. Harvey

It was a wet July evening. The three friends sat around the peat fire in Harborough’s den, pleasantly weary after their long tramp across the moors. Scott, the ironmaster, had been declaiming against modern education. His partner’s son had recently entered the business with everything to learn, and the business couldn’t afford to teach him. ‘I suppose,’ he said, ‘that from preparatory school to university, Wilkins must have spent the best of three thousand pounds on filling a suit of plus-fours with brawn. It’s too much. My boy is going to Steelborough grammar school. Then when he’s sixteen I shall send him to Germany so that he can learn from our competitors. Then he’ll put in a year in the office; afterwards, if he shows any ability, he can go up to Oxford. Of course he’ll be rusty and out of his stride, but he can mug up his Latin in the evenings as my shop stewards do with their industrial history and economics.’

‘Things aren’t as bad as you make out,’ said Freeman, the architect. ‘The trouble I find with schools is in choosing the right one where so many are excellent. I’ve entered my boy for one of those old country grammar schools that have been completely remodelled. Wells showed in The Undying Fire what an enlightened headmaster can do when he is given a free hand and isn’t buried alive in mortar and tradition.’

‘You’ll probably find,’ said Scott, ‘that it’s mostly eyewash ; no discipline, and a lot of talk about self-expression and education for service.’

‘There you’re wrong. I should say the discipline is too severe if anything. I heard only the other day from my young nephew that two boys had been expelled for a raid on a hen-roost or some such escapade; but I suppose there was more to it than met the eye. What are you smiling about, Harborough?’

‘It was something you said about headmasters and tradition. I was thinking about tradition and boys. Rum, secretive little beggars. It seems to me quite possible that there is a wealth of hidden lore passed on from one generation of schoolboys to another that it might be well worth while for a psychologist or an anthropologist to investigate. I remember at my first school writing some lines of doggerel in my books. They were really an imprecation against anyone who should steal them. I’ve seen practically the same words in old monkish manuscripts; they go back to the time when books were of value. But it was on the fly-leaves of Abbott’s Via Latina and Lock’s Arithmetic that I wrote them. Nobody would want to steal those books. Why should boys start to spin tops at a certain season of the year? The date is not fixed by shopkeepers, parents are not consulted, and though saints have been flogged to death I have found no connection between top whipping and the church calendar. The matter is decided for them by an unbroken tradition, handed down, not from father to son, but from boy to boy. Nursery rhymes are not perhaps a case in point, though they are stuffed with odd bits of folklore. I remember being taught a game that was played with knotted handkerchiefs manipulated by the fingers to the accompaniment of a rhyme which began: “Father Confessor, I’ve come to confess.” My instructor, aged eight, was the son of a High Church vicar. I don’t know what would have happened if old Tomlinson had heard the last verse:

“Father Confessor, what shall I do?”

“Go to Rome and kiss the Pope’s toe.”

“Father Confessor, I’d rather kiss you.”

“Well, child, do.” ’

‘What was the origin of that little piece of doggerel? ’ asked Freeman. ‘It’s new to me.’

‘I don’t know,’ Harborough replied. ‘I’ve never seen it in print. But behind the noddings of the knotted handkerchiefs and our childish giggles lurked something sinister. I seem to see the cloaked figure, cat-like and gliding, of one of those emissaries of the Church of Rome that creep into the pages of George Borrow—hatred and fear masked in ribaldry. I could give you other examples, the holly and ivy carols, for instance, which used to be sung by boys and girls to the accompaniment of a dance, and which, according to some people, embody a crude form of nature worship.’

‘And the point of all this is what?’ asked Freeman.

‘That there is a body of tradition, ignored by the ordinary adult, handed down by one generation of children to another. If you want a really good example—a really bad example I should say, I’ll tell you the story of the Dabblers.’ He waited until Freeman and Scott had filled their pipes and then began.

‘When I came down from Oxford and before I was called to the Bar, I put in three miserable years at school teaching.’

Scott laughed.

‘I don’t envy the poor kids you cross-examined,’ he said.

‘As a matter of fact, I was more afraid of them than they of me. I got a job as usher at one of Freeman’s old grammar schools, only it had not been remodelled and the headmaster was a completely incompetent cleric. It was in the eastern counties. The town was dead-alive. The only thing that seemed to warm the hearts of the people there was a dull smouldering fire of gossip, and they all took turns in fanning the flame. But I mustn’t get away from the school. The buildings were old; the chapel had once been the choir of a monastic church. There was a fine tithe barn, and a few old stones and bases of pillars in the headmaster’s garden, but nothing more to show where monks had lived for centuries except a dried-up fish pond.

‘Late in June at the end of my first year, I was crossing the playground at night on my way to my lodgings in the High Street. It was after twelve. There wasn’t a breath of air, and the playing fields were covered with a thick mist from the river. There was something rather weird about the whole scene; it was all so still and silent. The night smelt stuffy; and then suddenly I heard the sound of singing. I don’t know where the voices came from nor how many voices there were, and not being musical I can’t give you any idea of the tune. It was very ragged with gaps in it, and there was something about it which I can only describe as disturbing. Anyhow I had no desire to investigate. I stood still for two or three minutes listening and then let myself out by the lodge gate into the deserted High Street. My bedroom above the tobacconist’s looked out on to a lane that led down to the river. Through the open window I could still hear, very faintly, the singing. Then a dog began to howl, and when after a quarter of an hour it stopped, the June night was again still. Next morning in the masters’ common room I asked if anyone could account for the singing.

‘ “It’s the Dabblers,” said old Moneypenny, the science master, “they usually appear about now.”

‘Of course I asked who the Dabblers were.

‘ “The Dabblers,” said Moneypenny, “are carol singers born out of their due time. They are certain lads of the village who, for reasons of their own, desire to remain anonymous; probably choir-boys with a grievance, who wish to pose as ghosts. And for goodness’ sake let sleeping dogs lie. We’ve thrashed out the Dabbler controversy so often that I’m heartily sick of it.”

‘He was a cross-grained customer and I took him at his word. But later on in the week I got hold of one of the junior masters and asked him what it all meant. It seemed an established fact that the singing did occur at this particular time of the year. It was a sore point with Moneypenny, because on one occasion when somebody had suggested that it might be boys from the schoolhouse skylarking he had completely lost his temper.

‘ “All the same,” said Atkinson, “it might just as well be our boys as any others. If you are game next year we’ll try to get to the bottom of it.”

‘I agreed and there the matter stood. As a matter of fact when the anniversary came round I had forgotten all about the thing. I had been taking the lower school in prep. The boys had been unusually restless—we were less than a month from the end of term—and it was with a sigh of relief that I turned into Atkinson’s study soon after eight to borrow an umbrella, for it was raining hard.

‘ “By the by,” he said, “tonight’s the night the Dabblers are due to appear. What about it?”

‘I told him that if he imagined that I was going to spend the hours between then and midnight in patrolling the school precincts in the rain, he was greatly mistaken.

‘ “That’s not my idea at all,” he said. “We won’t set foot out of doors. I’ll light the fire; I can manage a mixed grill of sorts on the gas ring and there are a couple of bottles of beer in the cupboard. If we hear the Dabblers we’ll quietly go the round of the dormitories and see if anyone is missing. If they are, we can await their return.”

‘The long and short of it was that I fell in with his proposal.

I had a lot of essays to correct on the Peasants’ Revolt—fancy kids of thirteen and fourteen being expected to write essays on anything—and I could go through them just as well by Atkinson’s fire as in my own cheerless little sitting-room.

‘It’s wonderful how welcome a fire can be in a sodden June. We forgot our lost summer as we sat beside it smoking, warming our memories in the glow from the embers.

‘ “Well,” said Atkinson at last, “it’s close on twelve. If the Dabblers are going to start, they are due about now.” He got up from his chair and drew aside the curtains.

‘ “Listen!” he said. Across the playground, from the direction of the playing-fields, came the sound of singing. The music—if it could be called such—lacked melody and rhythm and was broken by pauses; it was veiled, too, by the drip, drip of the rain and the splashing of water from the gutter spouts. For one moment I thought I saw lights moving, but my eyes must have been deceived by reflections on the window pane.

‘ “We’ll see if any of our birds have flown,” said Atkinson. He picked up an electric torch and we went the rounds of the dormitories. Everything was as it should be. The beds were all occupied, the boys all seemed to be asleep. It was a quarter-past twelve by the time we got back to Atkinson’s room. The music had ceased; I borrowed a mackintosh and ran home through the rain.

‘That was the last time I heard the Dabblers, but I was to hear of them again. Act II was staged up at Scapa. I’d been transferred to a hospital ship, with a dislocated shoulder for X-ray, and as luck would have it the right-hand cot to mine was occupied by a lieutenant, R.N.V.R., a fellow called Holster, who had been at old Edmed’s school a year or two before my time. From him I learned a little more about the Dabblers. It seemed that they were boys who for some reason or other kept up a school tradition. Holster thought that they got out of the house by means of the big wisteria outside B dormitory, after leaving carefully constructed dummies in their beds. On the night in June when the Dabblers were due to appear it was considered bad form to stay awake too long and very unhealthy to ask too many questions, so that the identity of the Dabblers remained a mystery. To the big and burly Holster there was nothing really mysterious about the thing; it was a schoolboys’ lark and nothing more. An unsatisfactory act, you will agree, and one which fails to carry the story forward. But with the third act the drama begins to move. You see I had the good luck to meet one of the Dabblers in the flesh.

‘Burlingham was badly shell-shocked in the war; a psychoanalyst took him in hand and he made a seemingly miraculous recovery. Then two years ago he had a partial relapse, and when I met him at Lady Byfleet’s he was going up to town three times a week for special treatment from some unqualified West End practitioner, who seemed to be getting at the root of the trouble. There was something extraordinarily likeable about the man. He had a whimsical sense of humour that must have been his salvation, and with it was combined a capacity for intense indignation that one doesn’t often meet with these days. We had a number of interesting talks together (part of his regime consisted of long crosscountry walks, and he was glad enough of a companion) but the one I naturally remember was when in a tirade against English educational methods he mentioned Dr Edmed’s name—“the head of a beastly little grammar school where I spent five of the most miserable years of my life.”

‘ “Three more than I did,” I replied.

‘ “Good God!” he said, “fancy you being a product of that place!”

‘ “I was one of the producers,” I answered. “I’m not proud of the fact; I usually keep it dark.”

‘ “There was a lot too much kept dark about that place,” said Burlingham. It was the second time he had used the words. As he uttered them, “that place” sounded almost the equivalent of an unnameable hell. We talked for a time about the school, of Edmed’s pomposity, of old Jacobson the porter —a man whose patient good humour shone alike on the just and on the unjust—of the rat hunts in the tithe barn on the last afternoons of term.

‘ “And now,” I said at last, “tell me about the Dabblers.”

‘He turned round on me like a flash and burst out laughing, a high-pitched, nervous laugh that, remembering his condition, made me sorry I had introduced the subject.

‘ “How damnably funny!” he said. “The man I go to in town asked me the same question only a fortnight ago. I broke an oath in telling him, but I don’t see why you shouldn’t know as well. Not that there is anything to know; it’s all a queer boyish nightmare without rhyme or reason. You see I was one of the Dabblers myself.”

‘It was a curious disjointed story that I got out of Burlingham. The Dabblers were a little society of five, sworn on solemn oath to secrecy. On a certain night in June, after warning had been given by their leader, they climbed out of the dormitories and met by the elm-tree in old Edmed’s garden. A raid was made on the doctor’s poultry run, and, having secured a fowl, they retired to the tithe barn, cut its throat, plucked and cleaned it, and then roasted it over a fire in a brazier while the rats looked on. The leader of the Dabblers produced sticks of incense; he lit his own from the fire, the others kindling theirs from his. Then all moved in slow procession to the summer-house in the corner of the doctor’s garden, singing as they went. There was no sense in the words they sang They weren’t English and they weren’t Latin. Burlingham described them as reminding him of the refrain in the old nursery rhyme:

There were three brothers over the sea,

Peri meri dixi domine.

They sent three presents unto me,

Petrum partrum paradisi tempore

Peri meri dixi domine.

‘ “And that was all? ” I said to him.

‘ “Yes,” he replied, “that was all there was to it; but—”

‘I expected the but.’

‘ “We were all of us frightened, horribly frightened. It was quite different from the ordinary schoolboy escapade. And yet there was fascination, too, in the fear. It was rather like,” and here he laughed, “dragging a deep pool for the body of someone who had been drowned. You didn’t know who it was, and you wondered what would turn up.”

‘I asked him a lot of questions but he hadn’t anything very definite to tell me. The Dabblers were boys in the lower and middle forms and with the exception of the leader their membership of the fraternity was limited to two years. Quite a number of the boys, according to Burlingham, must have been Dabblers, but they never talked about it and no one, as far as he knew, had broken his oath. The leader in his time was called Tancred, the most unpopular boy in the school, despite the fact that he was their best athlete. He was expelled following an incident that took place in chapel. Burlingham didn’t know what it was; he was away in the sick-room at the time, and the accounts, I gather, varied considerably.’

Harborough broke off to fill his pipe.

‘Act IV will follow immediately,’ he said.

‘All this is very interesting,’ observed Scott, ‘but I’m afraid that if it’s your object to curdle our blood you haven’t quite succeeded. And if you hope to spring a surprise on us in Act IV we must disillusion you.’ Freeman nodded assent.

‘ “Scott who Edgar Wallace read,” ’ he began. ‘We’re familiar nowadays with the whole bag of tricks. Black Mass is a certain winner; I put my money on him. Go on, Harborough.’

‘You don’t give a fellow half a chance, but I suppose you’re right. Act IV takes place in the study of the Rev. Montague Cuttier, vicar of St Mary Parbeloe, a former senior mathematics master, but before Edmed’s time-—a dear old boy, blind as a bat, and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. He knew nothing about the Dabblers. He wouldn’t. But he knew a very great deal about the past history of the school, when it wasn’t a school but a monastery. He used to do a little quiet excavating in the vacations and had discovered what he believed to be the stone that marked the tomb of Abbot Polegate. The man, it appeared, had a bad reputation for dabbling in forbidden mysteries.’

‘Hence the name Dabblers, I suppose,’ said Scott.

‘I’m not so sure,’ Harborough answered. ‘I think that more probably it’s derived from diabolos. But, anyhow, from old Cuttier I gathered that the abbot’s stone was where Edmed had placed his summer-house. Now doesn’t it all illustrate my theory beautifully? I admit that there are no thrills in the story. There’s nothing really supernatural about it. Only it does show the power of oral tradition when you think of a bastard form of the black mass surviving like this for hundreds of years under the very noses of the pedagogues.’

‘It shows too,’ said Freeman, ‘what we have to suffer from incompetent headmasters. Now at the place I was telling you about where I’ve entered my boy—and I wish I could show you their workshops and art rooms—they’ve got a fellow who is—’

‘What was the name of the school?’ interrupted Harborough.

‘Whitechurch Abbey.’

‘And a fortnight ago, you say, two boys were expelled for a raid on a hen roost?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, it’s the same place that I’ve been talking about. The Dabblers were out.’

‘Act V,’ said Scott, ‘and curtain. Harborough, you’ve got your thrill after all.’

Host Commentary

PseudoPod, Episode 930 for July 26th, 2024.

The Dabblers, by W.F. Harvey

Narrated by Tol; hosted by Scott Campbell audio by Chelsea Davis

Hey everyone, hope you’re all doing okay. I’m Scott, Assistant Editor at PseudoPod, your host for this week. Thank you to Kat for helping me out with subbing in. Life, don’t talk to me about life. I’m excited to talk about this week’s story, The Dabblers, by W.F. Harvey. This story first appeared in the 1928 collection The Beast with Five Fingers.

Your author this week is W. F. Harvey. William Fryer Harvey (1885-1937) was an English writer of short stories, most notably in the macabre and horror genres. Among his best-known stories are the powerful precognition tale “August Heat” (1910), and “The Beast with Five Fingers” (adapted for film in 1946 with Peter Lorre). In World War I he initially joined the Friends’ Ambulance Unit, but later served as a surgeon-lieutenant in the Royal Navy, and received the Albert Medal for Lifesaving. He received lung damage during a rescue operation, damage which troubled him for the rest of his life. He wrote his memoir, We Were Seven, in 1936. From the late 1920s to the early 1930s he lived in Switzerland with his wife, but nostalgia for his home country caused his return to England, dying in Letchworth in 1937 at the age of 52.

Narrator bio:

Tol had a varied career, including as a hostage negotiator, car repairer and professional artist. He’s currently a lawyer (mostly in the video gaming, AI and social media fields). Technically, he’s been trained by ninjas and the SAS. In his own time he’s re-learning French and the piano, and taking up cage fighting. He summers on the Côte d’Azur and winters in London, England (and wonders if those are the right way round).

And now we have a story for you, and we promise you, it’s true.

ENDCAP

Well done, you’ve survived another story. What did you think of The Dabblers by W.F. Harvey? If you’re a Patreon subscriber, we encourage you to pop over to our Discord channel and tell us.

This story is a tease. it gives you little hints here and there but never gives you the full monty. Think about it, what really happened in the story. A former schoolteacher finds out about a secret club of students and their odd traditional activities. That’s it. No one dies, nothing gets summoned, no gateways to hell. And yet…

We hear about the elaborate preparations the Dabblers make to sneak out. Full-on dummies are not easy to make. We hear about the stealing, killing and cooking of the chicken. Just a bit of larceny or a sacrifice? And of course, singing the Latin out loud. Major red flag. Added to that the legend of a former abbott possibly engaging in diabolical arts. Anti-Catholic propaganda or was there something occult going on? We don’t know. That’s where the horror is. A lot of the time,authors play with this by making the strange going on a possible delusion, a symptom of madness. But even then most will collapse the quantum superposition and tell us it’s one thing or another. Harvey leaves us in suspense, balanced between simple schoolboy shenanigans and something far worse.

Onto the subject of subscribing and support: PseudoPod is funded by you, our listeners, and we’re formally a non-profit. One-time donations are gratefully received and much appreciated, but what really makes a difference is subscribing. A $5 monthly Patreon donation gives us more than just money; it gives us stability, reliability, dependability and a well-maintained tower from which to operate, and trust us, you want that as much as we do.

If you can, please go to pseudopod.org and sign up by clicking on “feed the pod”. If you have any questions about how to support EA and ways to give, please reach out to us at donations@escapeartists.net.

If you can’t afford to support us financially, then please consider leaving reviews of our episodes, or generally talking about them on whichever form of social media you… can’t stay away from this week. We now have a Bluesky account and we’d love to see you there: find us at @pseudopod.org. If you like merch, you can also support us by buying hoodies, t-shirts and other bits and pieces from the Escape Artists Voidmerch store. The link is in various places, including our pinned tweet.

PseudoPod is part of the Escape Artists Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, and this episode is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Download and listen to the episode on any device you like, but don’t change it or sell it. Theme music is by permission of Anders Manga.

And finally, PseudoPod, and Robert Frost, know…. We dance round in a ring and suppose, but this secret sits in the middle and knows

See you soon, folks, take care, stay safe.

About the Author

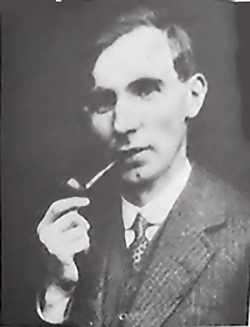

W.F. Harvey

William Fryer Harvey (1885-1937) was an English writer of short stories, most notably in the macabre and horror genres. Among his best-known stories are the powerful precognition tale “August Heat” (1910), and “The Beast with Five Fingers” (adapted for film in 1946 with Peter Lorre). In World War I he initially joined the Friends’ Ambulance Unit, but later served as a surgeon-lieutenant in the Royal Navy, and received the Albert Medal for Lifesaving. He received lung damage during a rescue operation, damage which troubled him for the rest of his life. He wrote his memoir, We Were Seven, in 1936. From the late 1920s to the early 1930s he lived in Switzerland with his wife, but nostalgia for his home country caused his return to England, dying in Letchworth in 1937 at the age of 52.

About the Narrator

Tol

Tol has had a varied career, including as a hostage negotiator, car repairer and professional artist. He’s currently a lawyer (mostly in the video gaming, AI and social media fields). Technically, he’s been trained by ninjas and the SAS. In his own time he’s re-learning French and the piano, and taking up cage fighting. He summers on the Côte d’Azur and winters in London, England (and wonders if those are the right way round).