PseudoPod 917: Henry

Henry

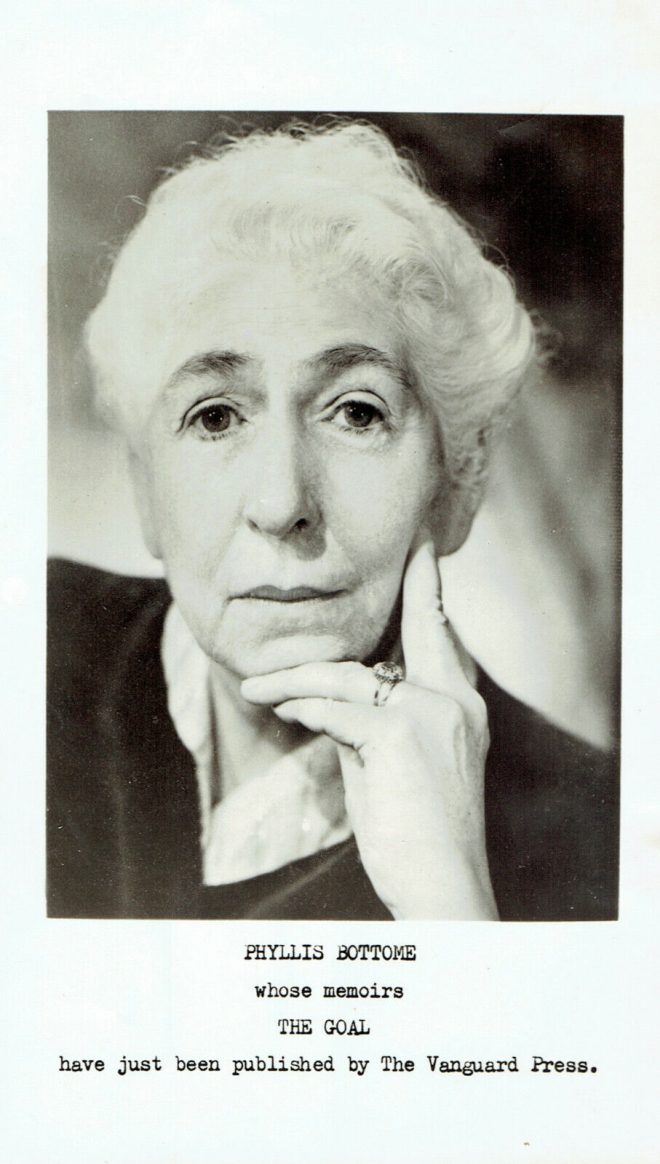

by Phyllis Bottome

For four hours every morning and for twenty minutes before a large audience at night Fletcher was locked up with murder.

It glared at him from twelve pairs of amber eyes ; it clawed the air close to him, it spat naked hate at him, and watched with uninterrupted intensity to catch him for one moment off his guard.

Fletcher had only his will and his eyes to keep death at bay.

Of course, outside the cage into which Fletcher shut himself nightly with his twelve tigers were the keepers, standing at intervals around it with concealed pistols ; but they were outside it. The idea was that if anything happened to Fletcher they would be able by prompt action to get him out alive ; but they had his private instructions to do nothing of the kind, to shoot straight at his heart, and pick off the guilty tiger afterwards to cover their intention. Fletcher knew better than to try to preserve anything the tigers left of him, if once they had started in.

The lion-tamer in the next cage was better off than Fletcher, he was intoxicated by a rowdy vanity which dimmed fear. He stripped himself half naked every night, covered himself with ribbons, and thought so much of himself that he hardly noticed his lions. Besides, his lions had all been born in captivity, were slightly doped, and were only lions.

Fletcher’s tigers weren’t doped because dope dulled their fears of the whip and didn’t dull their ferocity; captivity softened nothing in them, and they hated man.

Fletcher had taught tigers since he was a child ; his father had started him on baby tigers, who were charming. They hurt you as much as they could with an absent-minded roguishness difficult to resist; what was death to you was play to them; but as they couldn’t kill him, all the baby tigers did was to harden Fletcher and teach him to move about quickly. Speed is the tiger’s long suit, and Fletcher learned to beat them at it. He knew by a long-trained instinct when a tiger was going to move, and moved quicker so as to be somewhere else. He learned that tigers must be treated like an audience, though for different reasons; you must not turn your back upon them, because tigers associate backs with springs.

Fletcher’s swift eyes moved with the flickering sureness of lightning—even quicker than lightning, for while lightning has the leisure to strike, Fletcher had to avoid being struck by something as quick as a flash and much more terrible.

After a few months the baby tigers could only be taught by fear, fear of whiplash, fear of a pocket pistol which stung them with blank cartridges : and above all the mysterious fear of the human eye. Fletcher’s father used to make him sit opposite him for hours practising eyes. When he was only ten years old Fletcher had learned never to show a tiger that he was afraid of him.

“ If you ain’t afraid of a tiger, you’re a fool,” his father told him; “ but if you show a tiger you’re afraid of him, you won’t even be a fool long!”

The first thing Fletcher taught his tigers, one by one in their cages, was to catch his eye; then he stared them down. He had to show them that his power of mesmerism was stronger than theirs ; if once they believed this, they might believe that his power to strike was also stronger. Once Fletcher had accustomed tigers to be out-faced, he could stay in their cages for hours in comparative safety.

The next stage was to get them used to noise and light. Tigers dislike noise and light, and they wanted to take it out of Fletcher when he exposed them to it.

When it came to the actual trick teaching Fletcher relied on his voice and a long, stinging whip. The Lion-tamer roared at his lions ; Fletcher’s voice was not loud, but it was as noticeable as a warning bell. It checked his tigers like the crack of a pistol.

For four hours every morning Fletcher, who was as kind as he was intrepid, frightened his tigers into doing tricks. He rewarded them as well; after they had been frightened enough to sit on tubs he threw them bits of raw meat. He wanted them to associate tubs with pieces of raw meat, and not sitting on tubs with whips ; attempting to attack him, which they did during all transition stages, he wanted them to associate with flashes from his pocket pistol, followed by the impact of very unpleasant sensations. Their dislike of the pistol was an important point; they had to learn to dislike it so much that they would, for the sake of their dislike, sacrifice their fond desire to obliterate Fletcher.

Fletcher took them one by one at first, and then rehearsed them gradually together. It was during the single lessons that he discovered Henry.

Henry had been bought, rather older than the other tigers, from a drunken sailor. The drunken sailor had tearfully persisted that Henry was not as other tigers, and that selling him at all was like being asked to part with a talented and only child.

“ ’E ‘as a ’eart! ” Henry’s first proprietor repeated over and over again.

Fletcher, however, suspected this fanciful statement of being a mere ruse to raise Henry’s price, and watchfully disregarded its implications.

For some time afterwards Henry bore out Fletcher’s suspicions. He snarled at all the keepers, showed his teeth and clawed the air close to Fletcher’s head exactly like the eleven other tigers, only with more vim. He was a very fine young tiger, exceptionally powerful and large; the polished corners of the Temple did not shine more brilliantly than the lustrous striped skin on Henry’s back, and when his painted, impassive face, heavy and expressionless as a Hindoo idol’s, broke up into activity the very devils believed and trembled. Fletcher believed, but he didn’t tremble—he only sat longer and longer, closer and closer to Henry’s cage, watching.

The first day he went inside there seemed no good reason, either to Henry or to himself, why he should live to get out. The second day something curious happened. While he was attempting to outstare Henry and Henry was stalking him to get between him and the cage door a flash of something like recognition came into Henry’s eyes, a kind of “ Hail fellow well met! ” He stopped stalking and sat down.

Fletcher held him firmly with his eyes ; the great painted head sank down, and amber eyes blurred and closed under Fletcher’s penetrating gaze. A loud noise filled the cage, a loud, contented, pleasant noise. Henry was purring!

Fletcher’s voice changed from the sharp brief order like the crack of a whip into a persuasive companionable drawl. Henry’s eyes reopened; he rose, stood rigid for a moment, and then slowly the rigidity melted out of his powerful form. Once more that answering look came into the tiger’s eyes. He stared straight at Fletcher without blinking and jumped on his tub. He sat on it impassively, his tail waving, his great jaws closed. He eyed Fletcher attentively and without hate. Then Fletcher knew that this tiger was not as other tigers, not as any other tiger.

He threw down his whip, Henry never moved; he approached ; Henry lifted his lip to snarl, thought better of it, and permitted the approach. Fletcher took his life in his hand and touched Henry.

Henry snarled mildly, but his great claws remained closed ; his eyes expressed nothing but a gentle warning ; they simply said : “You know I don t like being touched ; be careful, I might have to claw you ! ” Fletcher gave a brief nod; he knew the margin of safety was slight, but he had a margin. He could do something with Henry.

Hour after hour every day he taught Henry, but he taught him without a pistol or whip. It was unnecessary to use anything beyond his voice and his eyes. Henry read his eyes eagerly. When he failed to catch Fletcher’s meaning, Fletcher’s voice helped him out. Henry did not always understand even Fletcher’s voice, but where he differed from the other tigers was that he wished to understand ; nor had he from the first the slightest inclination to kill Fletcher.

He used to sit for hours at the back of his cage waiting for Fletcher. When he heard far off—unbelievably far off— the sound of Fletcher’s step, he moved forward to the front of his cage and prowled restlessly to and fro till Fletcher unlocked the door and entered. Then Henry would crouch back a little, politely, from no desire to avoid his friend, but as a mere tribute to the superior power he felt in Fletcher. Directly Fletcher spoke, he came forward proudly and exchanged their wordless eye language.

Henry like doing his tricks alone with Fletcher. He jumped on and off his tub following the mere wave of Fletcher’s hand. He soon went further, jumped on a high stool and leapt through a large white paper disc held up by Fletcher. Although the disc looked as if he couldn’t possibly get through it, yet the clean white sheet always yielded to his impact; he did get through it, blinking a little, but feeling a curious pride that he had faced the odious thing—and pleased Fletcher.

He let Fletcher sit on his back, though the mere touch of an alien creature was repulsive to him. But he stood perfectly still, his hair rising a little, his teeth bared, a growl half suffocated in his throat. He told himself it was Fletcher. He must control his impulse to fling him off and tear him up.

In all the rehearsals and performances in the huge arena, full of strange noises, blocked with alien human beings, Henry led the other tigers; and though Fletcher’s influence over him was weakened, he still recognised it. Fletcher seemed farther away from him at these times, less sympathetic and godlike, but Henry tried hard to follow the intense persuasive eyes and the brief emphatic voice ; he would not lose touch even with this attenuated ghost of Fletcher.

It was with Henry and Henry alone that Fletcher dared his nightly stunt, dropped the whip and stick at his feet and let Henry do his tricks as he did them in his cage alone, with nothing beyond Fletcher’s eyes and voice to control him. The other eleven tigers, beaten, glaring and snarling on to their tubs, sat impassively despising Henry’s unnatural docility. He had the chance they had always wanted, and he didn’t take it—what kind of tiger was he?

But Henry ignored the other tigers. Reluctantly standing with all four feet together on his tub, he contemplated a further triumph. Fletcher stood before him, holding a stick between his hands and above his head, intimately, compellingly, through the language of his eyes Fletcher told Henry to jump from his tub over his head. What Fletcher said was : “ Come on, old thing ! Jump! Come on ! I’ll duck in time. You won’t hurt me I It’s my stunt! Stretch your old paws together and jump!”

And Henry jumped. He hated the dazzling lights, loathed the hard, unexpected, senseless sounds which followed his leap, and he was secretly terrified that he would land on Fletcher. But it was very satisfactory when, after his rush through the air, he found he hadn’t touched Fletcher, but had landed on another tub carefully prepared for him ; and Fletcher said to him as plainly as possible before he did the drawer trick with the other tigers : “ Well! You are a one-er, and no mistake!”

The drawer trick was the worst of Fletcher’s stunts. He had to put a table in the middle of the cage and whip each tiger up to it. When he had them placed each on his tub around the table he had to feed them with a piece of raw meat deftly thrown at the exact angle to reach the special tiger for which it was intended, and to avoid contact with eleven other tigers ripe to dispute his intention. Fletcher couldn’t afford the slightest mistake or a fraction of delay.

Each tiger had to have in turn his piece of raw meat, and the drawer shut after it—opened—the next morsel thrown exactly into the grasp of the next tiger, and so on until the twelve were fed.

Fletcher always placed Henry at his back. Henry snatched in turn his piece of raw meat, but he made no attempt, as the other tigers always did, to take anyone else’s; and Fletcher felt the safer for knowing that Henry was at his back. He counted on Henry’s power to protect him more than he counted on the four keepers standing outside the cage with their pistols. More than once, when one of the other tigers turned restive, Fletcher had found Henry rigid, but very light on his toes, close to his side, between him and danger.

The circus manager spoke to Fletcher warningly about his foolish infatuation for Henry.

“ Mark my words, Fletcher,” he said, “the tiger doesn’t live that wouldn’t do you in if it could. You give Henry too many chances—one day he’ll take one of them.” But Fletcher only laughed. He knew Henry; he had seen the soul of the great tiger leap to his eyes and shine there in answer to his own eyes. A man does not kill his god; at least not willingly. It is said that two thousand years ago he did some such thing, through ignorance, but Fletcher forgot this incident. Besides, on the whole, he believed more in Henry than he did in his fellow men.

This was not surprising, because Fletcher had very little time for human fellowship. When he was not teaching tigers not to kill him, he rested from the exhaustion of the nerves which comes from a prolonged companionship with eager, potential murderers ; and the rest of the time Fletcher boasted of Henry to the lion-tamer, and taught Henry new tricks.

Macormack, the lion-tamer, had a very good stunt lion, and he was extravagantly jealous of Henry. He could not make his lion go out backwards before him from the arena cage into the passage as Henry had learned to do before Fletcher, and when he had tried Ajax had, not seriously, but with an intention rather more than playful, flung him against the bars of the cage.

Host Commentary

PseudoPod 917

April 26th 2024

Henry by Phyllis Bottome

Narrated by Simon Meddings

Audio Production by Chelsea Davis

Hosted by Alasdair Stuart

Hello everyone, and welcome to PseudoPod, the weekly horror podcast. I’m Alasdair, your host and this week’s story comes to us from Phyllis Bottome, an author with a hell of a life story. Bottome studied individual psychology under Alfred Adler while in Vienna, and with her husband (who was secretly MI6 Head of Station with responsibility for Austria, Hungary and Yugoslavia) she opened a language school in 1924 in Kitzbühel in Austria, which was also intended to be a community/educational laboratory to determine how psychology and educational theory could cure the ills of nations (one of their more famous pupils was author Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond). Bottome was an active anti-fascist, and wrote many novels in her lifetime, a number of which were turned into films.

Your narrator this week is Simon Meddings. So take your seats because the show is about to start and it’s going to tell you the truth.

The inherent horror of the story is the two-edged sword of privilege and cruelty that animal taming represents. Fletcher’s work is in no way vital and tied intimately to his ego and the power dynamics of the circus staff. He views Henry as an equal. Henry views him as a god. The betrayal of both, the tragedy of it all, is all there the moment Henry and Fletcher step into the cage together. It’s just a matter of revealing it. Discovering your god is an idiot made of blood and gristle. Discovering your favourite tiger is your killer, not your friend.

‘What sort of tiger are you?’ begs the follow up ‘What sort of tiger do you think you are?’ . That question is patiently waiting with bright, sharp eyes and brighter, sharper teeth on a stool at one end of the cage. Control and precision and calm and tension all expressed in each careful movement, each precise sentence. Ego, and arrogance, stupidity and tragedy, all walking just behind them. Henry knows what sort of tiger he is. Fletcher thinks he knows what sort of man he is. That gap is what dooms them both and leads us to a roar, and a gunshot and the big finish no one wanted and everyone but Fletcher knew was coming.

‘A man does not kill his own god’ is a sentence so wrapped up in privilege and assumption it can’t see the teeth descending towards it. Fletcher buys into his own myth, tells himself the universe that he’s building one word, one step, one look at a time is one only he can control. The only person who believes that is him. The comfort here comes from the fact he dies believing it. The horror, the tragedy, comes from the price Henry pays for that. Bleak and elegant stuff. Thanks to all.

As is always the case, we rely on you to pay our authors, our narrators and our crew, and to cover our costs. We’re entirely donation funded and last year that changed in some very exciting ways with becoming a registered US nonprofit. We ran a great end of year campaign in 2023 to raise awareness about all the new ways you can help us out like for example if you pay taxes in the US, you might be able to claim a deduction. Check out the short metacast on escapeartists.net for more ideas, and how to get in touch if you think of something else that’s more meaningful to you.

As is always the case, we rdeas, and how to get in touch if you think of something else that’s more meaningful to you.

One-time donations are fantastic and gratefully received, but what really makes a difference is subscribing. Subscriptions get us stability and a reliable income we use to bring free and accessible audio fiction to the world. You can subscribe for a monthly or annual donation through PayPal or Patreon. And if you sign up for an annual subscription on Patreon, there’s a discount available from now until the end of the year.

Not only do you help us out immensely when you subscribe or donate but you get access to a raft of bonus audio. You help us, we help you and everything becomes just a little easier. Even if you can’t donate financially, please consider spreading the word about us. If you liked an episode then please consider sharing it on social media, or blogging about us or leaving a review it really does all help and thank you once again.

We’ll be back next week with the magnificently titled The Dreadful and Specific Monster of Starosibirsk by Christina Ten and narrated by Yaroslav Barsukov. Chelsea will be on audio duties and I’ll be your host.

Then, as now it will be a production of the Escape Artists Foundation and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial No Derivatives 4.0 International license.

PseudoPod leaves you this week with this poem from Nael, age 6.

The tiger

He destroyed his cage

Yes

YES

The tiger is out

We’ll see you next time, folks. Until then, have fun.

About the Author

Phyllis Bottome

Phyllis Bottome (1884–1963) was a British novelist and short story writer. Bottome studied individual psychology under Alred Adler while in Vienna, and with her husband (who was secretly MI6 Head of Station with responsibility for Austria, Hungary and Yugoslavia) she opened a language school in 1924 in Kitzbühel in Austria, which was also intended to be a community/educational laboratory to determine how psychology and educational theory could cure the ills of nations (one of their more famous pupils was author Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond). Bottome was an active anti-fascist, and wrote many novels in her lifetime, a number of which were turned into films.

About the Narrator

Simon Meddings

Simon Meddings is a freelance writer and scriptwriter, he is also an actor and has recently appeared in the horror film Polterheist directed by David Gilbank. Simon hosts the Waffle On Podcast all about classic television shows and films from around the world. Available on itunes, Stitcher radio and direct at Podbean.